Writers as Actors: ‘The Rosenberg/Strange Fruit Project’ Illustrates the Difficulty of Mastering Both

As a writer, John Jiler has created a play with a range of personalities that offers rich opportunities for the right performer; unfortunately, his acting performance doesn’t live up to his prose.

More than a few playwrights double as actors, but not many prove masterful in both arenas; Tracy Letts and the late Sam Shepard come to mind. John Jiler, who wrote and is the sole speaking performer in “The Rosenberg/Strange Fruit Project,” is far less well-known, but he has been prolific — particularly as a writer, winning awards and acclaim for his plays and nonfiction prose.

Since the late aughts, Mr. Jiler has unveiled three one-man shows; “Rosenberg,” the third, previewed off-Broadway at 59E59 Theaters last summer and is now being produced there. The new play requires its sole performer to juggle numerous historical characters, central among them Robert Meeropol — born Robert Rosenberg, the younger son of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were executed on charges that they had spied for the Soviet Union when he was just 6 years old.

Robert and his elder sibling were adopted by another man featured as a character in the show: Abel Meeropol, the schoolteacher and poet who wrote lyrics and later co-wrote music for “Strange Fruit,” the lyrical, harrowing account of a lynching made famous by Billie Holiday. As an adult, Robert followed in the path of his birth parents and adoptive father, advocating for various progressive causes including the establishment of Julius and Ethel’s innocence.

“Rosenberg” is littered with other colorful and significant figures, from Holiday and the sociologist and civil rights champion W.E.B. DuBois to the judge who sentenced Julius and Ethel to death, Irving Kaufman, and the Texas Republican who during Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration became the first woman to serve on a presidential Cabinet, Oveta Culp.

Staged against David L. Arsenault’s spare set, with columns holding props that help Mr. Jiler distinguish between characters — a Brooklyn Dodgers cap for young Robert, who ages throughout the show; an American-flag scarf that Oveta can literally wrap herself in — the play is essentially a series of monologues, most of them engagingly written. Mr. Jiler is careful to temper his indignation with humor and whimsy, and certainly the range of personalities here offers rich opportunities for the right performer.

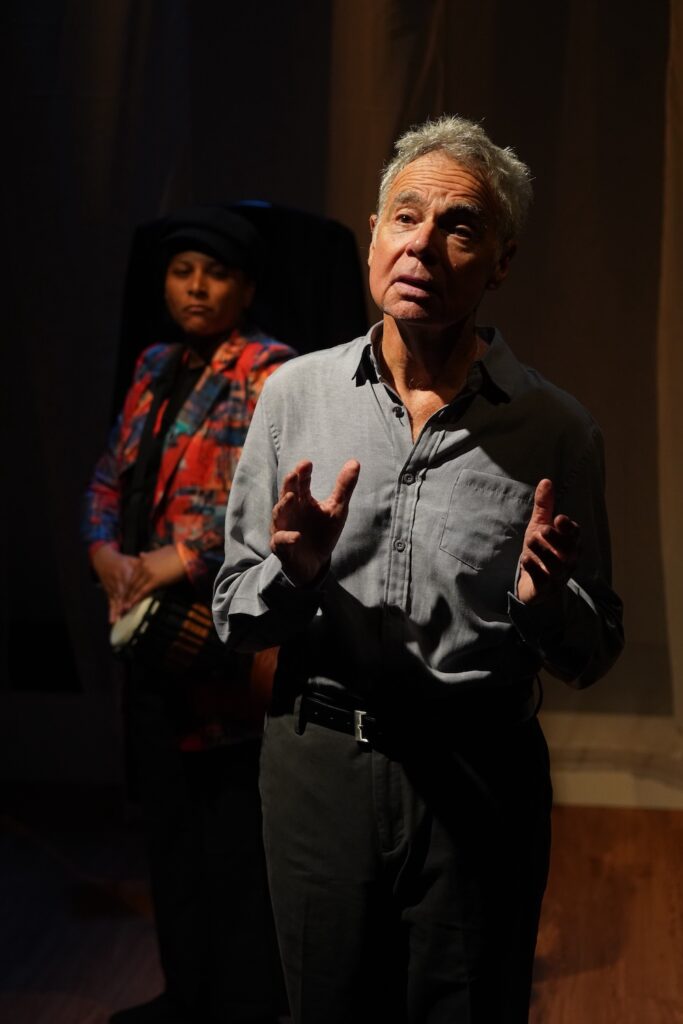

The problem, sadly, is that Mr. Jiler is not that performer. I’ll admit that I haven’t seen him in previous productions, of either his own work or other plays, but here, at least — under the guidance of Margarett Perry, an accomplished director — he exudes a self-consciousness that’s evident from the moment he greets the audience, before he has even tried on another role.

This quality proves less of a liability when Mr. Jiler is playing Robert, a part that allows him to evolve into a passionate but somewhat awkward young man from a forlorn child. Yet even in this case, the performance, while endearing, has the feel of a drama class exercise: Mr. Jiler imbues the character with an exaggerated restlessness and physical tics — rubbing his head, for instance — that linger as he grows older and more confident.

Elsewhere, Mr. Jiler’s acting simply doesn’t measure up to the agility and wit that inform much of his writing. He’s accompanied onstage by the clarinetist “Sweet” Lee Odom, who offers strains of jazz and klezmer to drive home the outsized participation, and suffering, of Black and Jewish citizens in the struggle for social justice.

Toward the end of “Rosenberg,” Mr. Jiler turns up as Lewis F. Powell, Jr., who prior to joining the Supreme Court in 1972 emerged as a key supporter of corporate interests. Delivering a speech plainly modeled on the Lewis Memo, which proposed a political strategy for promoting those interests, the actor finally summons a fire and menace worthy of his writing.

Alas, it’s too little and too late, even for a piece that clocks in at less than 80 minutes. Given the fascinating material here, that’s a shame.