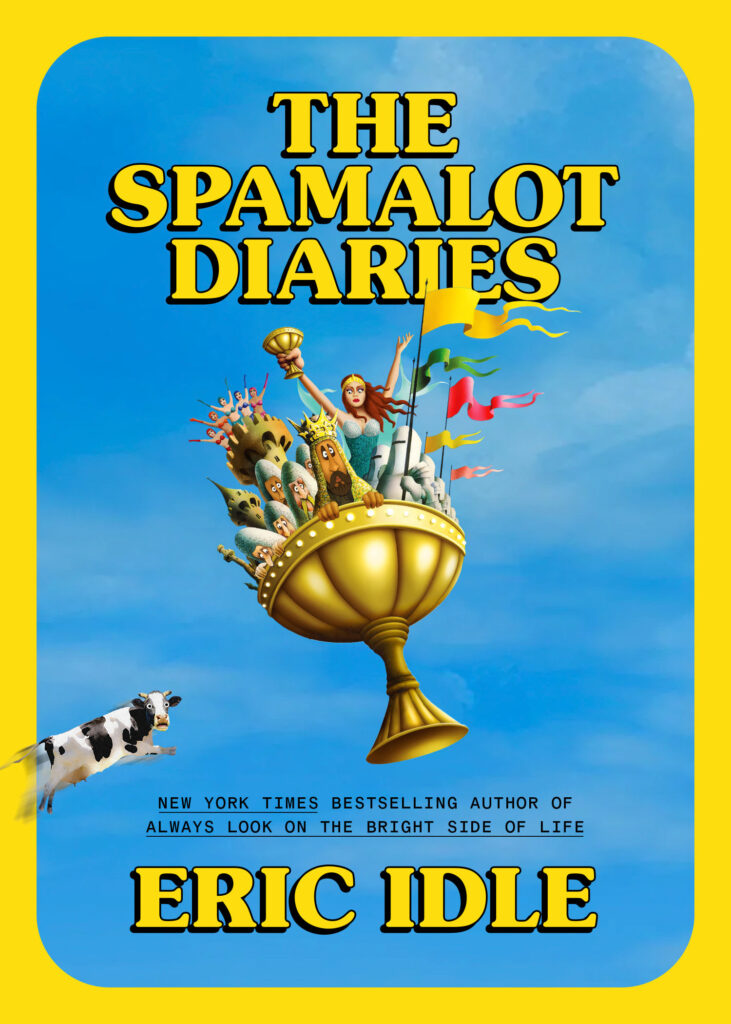

With ‘The Spamalot Diaries,’ Monty Python’s Eric Idle Details the Process of Bringing the Show to Broadway

Idle, working along with longtime musical collaborator John Du Prez and director Mike Nichols, was the engine in transforming a cult movie, ‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail,’ into a theatrical milestone.

Eric Idle in Conversation With Alan Zweibel

Symphony Space

October 8

What’s surprising about the new book by Eric Idle, “The Spamalot Diaries,” is how given the writer, actor, and comedian is to dad jokes. You know, those lame puns or we-saw-them-coming asides that are, according to the popular imagination, the exclusive purview of middle-aged men.

I mean, dubbing Wagner’s “The Ring Cycle” the “rinse cycle” or stating: “There is no over the top” in Las Vegas. “Only over the topless.” Oof. As Mr. Idle once had it in another context: “Say no more.”

It’s not always this way for Mr. Idle: Having seen him in various public programs over the years, I’ve laughed heartily and sometimes helplessly at his blessed nonsense.

Mr. Idle was one-sixth of the braintrust behind the British ensemble Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Working along with Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, he created any number of indelible characters and outlandish situations over the course of four television seasons, four feature films, and, not counting compilations, more than four but less than six albums. Within this relatively modest corpus a comedic tidal wave was born.

The standard line on the Pythons is that they were the comedic equivalent of the Beatles. In terms of chronology, there was a kind of passing of the karmic torch: the first episode of the Python television series appeared on BBC1 days after the release of the Fab Four’s final album, “Abbey Road.” The Beatles were fans of the irreverent comedy troupe — particularly George Harrison, who would later become a close friend to Mr. Idle.

Python and the Beatles shared senses of humor mined directly from the soil of their lonely island state. Somewhere, someone has concocted a Venn diagram connecting our heroes with William Shakespeare, William Hogarth, Edward Lear, and the Goon Show. The Pythons are as ineradicably British as cricket, spotted dick, and eating fried food out of yesterday’s newspaper. How on earth did they fare so well in America?

Naysayers will tell you that Python appeals to college-educated snobs, and they have a point: Few entertainers have been as brazen in flaunting their IQs. Yet rarely do the educated classes bare their naughty bits with as much audacity. When the Public Broadcasting System began running the television series in 1974 and their second motion picture, “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” (1975), hit these shores — well, there was no turning back.

“Holy Grail” is a hodgepodge of a picture — “Life of Brian” (1979) and the underrated “Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life” (1983) are more assured — but it has proven remarkably resilient in terms of maintaining a fanbase. The film was the basis for a Broadway play, “Spamalot,” and, though a different creature altogether, the stage show improved upon its model. Mr. Idle, working along with longtime musical collaborator John Du Prez, was the engine in transforming a cult movie into a theatrical milestone.

“The Spamalot Diaries” is culled from journal entries and sundry emails detailing the genesis, shaping, and mounting of the Broadway play. As such, it reaffirms the collaborative nature of the theater. Messrs. Idle and Du Prez worked in conjunction with director Mike Nichols, choreographer Casey Nicholaw, a host of stagehands, a bevy of money-men, and a cast of ardent Python devotees. Try ironing out the kinks in that conglomeration.

“Spamalot” did boffo box office and reigned at the Tonys as Best Musical. The majority of “The Spamalot Diaries” underlines the give-and-take of the creative process and the pitfalls of adapting a well-known and beloved property. Although Mr. Idle maintains a jaunty spirit throughout the book, he does, at times, exhibit frustration and sometimes despair.

Mr. Idle was often at loggerheads with Nichols, a friend whose perfectionism was a blessing, a wild card, and a bother. The erstwhile director was more a maven of the Broadway stage than Mr. Idle, and he was perpetually trying to massage the anarchic side of Python into something more mainstream. Mr. Idle writes of how Nichols achieved a fleeting state of happiness upon slotting “Spamalot” as a meditation on the British class system. For Mike, Mr. Idle writes, “everything must have meaning.”

To each his literal own, I guess. Mr. Idle’s book segues, at times, into his personal travails with health and family — being a living legend doesn’t always correlate with physical and emotional tranquility — and is prone to the egregious dropping of names. He’s earned the right to do so, I guess, and there’s no gainsaying the ultimate triumph of “Spamalot” or, for that matter, Mr. Idle’s contribution to the broader culture. “The Spamalot Diaries” offers a peek into one dad’s brain.