With ‘Grandiloquent,’ Comedian Gary Gulman Recounts His Time Growing Up Awkward

Few high-profile comics acknowledge their thirst for affirmation, or the past and ongoing challenges informing it, as transparently or relentlessly as Gulman does in his new one-man show.

Entertainers can be extremely needy people, and none more so than standup comedians, who both mine and risk personal humiliation in the pursuit of that instant gratification provided by an audience’s laughter and applause. Yet few high-profile comics acknowledge their thirst for affirmation, or the past and ongoing challenges informing it, as transparently or relentlessly as Gary Gulman does in his new one-man show, “Grandiloquent.”

Since gaining national recognition more than 20 years ago on a reality TV series, “Last Comic Standing,” Mr. Gulman has documented his bouts with depression and anxiety; his television specials include “The Great Depresh,” and he wrote a memoir called “Misfit: Growing Up Awkward in the ’80s.” The latter was an obvious springboard for “Grandiloquent,” which kicks off with an homage to a rather more famous title, “The Monster at the End of This Book,” an early childhood classic exploring fear through the eyes of Grover, the duly beloved Muppet.

Reading plays a central role in this 90-minute show, in fact, and in the acute self-doubt integral to Mr. Gulman’s mental health struggles. In the late ’70s, his father, who had split with the comedian’s mother years before, apparently insisted that his son — the youngest of three — repeat the first grade, notwithstanding the kid’s superior academic performance.

Mr. Gulman had been in the top reading group in his class, an accomplishment that is marked here repeatedly — and with a gusto that will remind anyone whose children have attended elementary school of certain parents who boast at parties about what color-coded or otherwise noted milestones their own little geniuses have achieved.

Granted, Mr. Gulman’s memory of his prowess is used here for comedic effect — as are the literary and cultural references he spreads liberally through this piece, ranging from “Moby-Dick” to psychologist Abraham Maslow to Mookie Blaylock, a basketball player whose name was considered by members of Pearl Jam for their band moniker. At the preview I attended, Mr. Gulman departed from the script, as I assume he usually does, to jokingly chide audience members who didn’t seem to pick up on a few other conspicuous allusions.

There’s often a fine line between mocking and indulging in snobbery, but Mr. Gulman generally avoids crossing it both by virtue of his flagrant insecurity and by simply being funny. Recalling his intense relationship with his single mother — “basically she was my first wife,” he quips — he observes, “Some moms greet adversity with poise … Barbara Gulman greeted adversity with, ‘Uh oh, uh oh, that’s all I need.’”

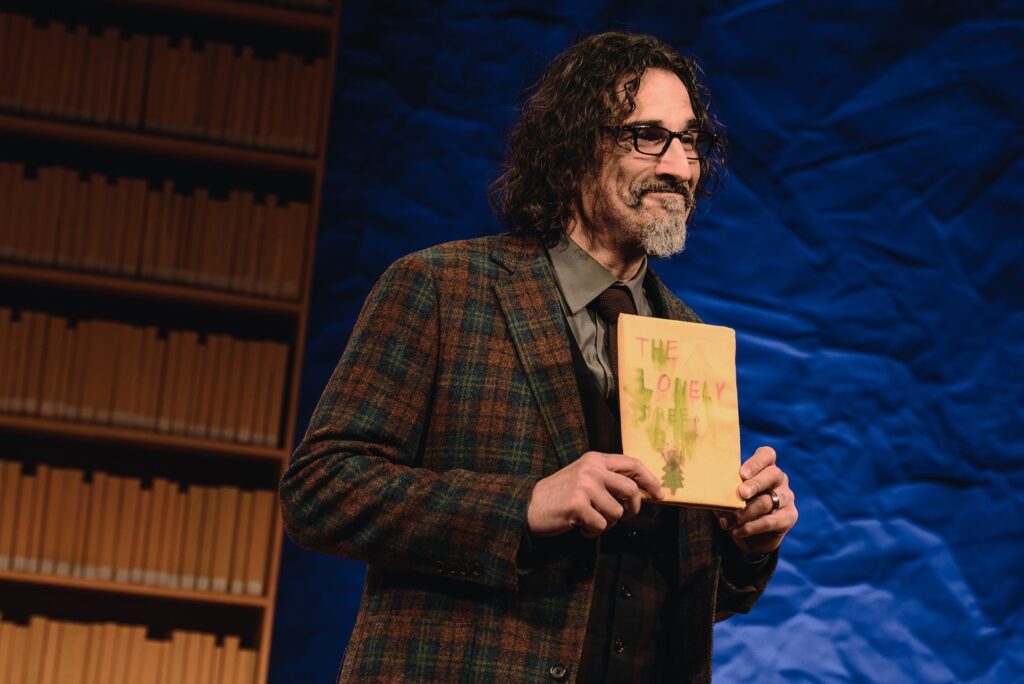

We learn that when Mr. Gulman’s father brought to a publisher a book his son wrote for a second-grade project, called “The Lonely Tree,” the professional advised him to “rush this kid to an early childhood development specialist, because I haven’t seen an allegory this unambiguous since ‘The Chronicles of Narnia.’” It’s suggested that the work should be subtitled, “A Cry for Help.”

Throughout, director Moritz von Stuelpnagel accommodates Mr. Gulman’s wry delivery — cannily halting at points, then suddenly razor-sharp. “Grandiloquent” lags a bit toward the end, as the performer and writer evinces his enduring need to prove himself intellectually by re-enacting a “three-hour lecture on the grunge era,” his response to his wife’s simple question about a song. The segment actually takes only several minutes, but it feels longer.

There are also twinges of self-pity, though they’re mitigated by self-awareness and a sense of genuine, growing resolve. “I’m not sure we owe our pain and suffering any gratitude,” Mr. Gulman muses; if his own inner monsters are clearly more complicated than Grover, he has at least found a productive way of dealing with them.