Vik Muniz Recreates American Icons With Shredded Fiat Currency, Questioning What Our Collective History Is Made Of

His witty send ups both enshrine and subvert images from our collective zeitgeist with the recycled debris of consumer culture.

Vik Muniz: ‘Scraps and Legal Tender’

Sikkema Jenkins, 530 West 22nd Street, New York, NY

Through April 27, 2024

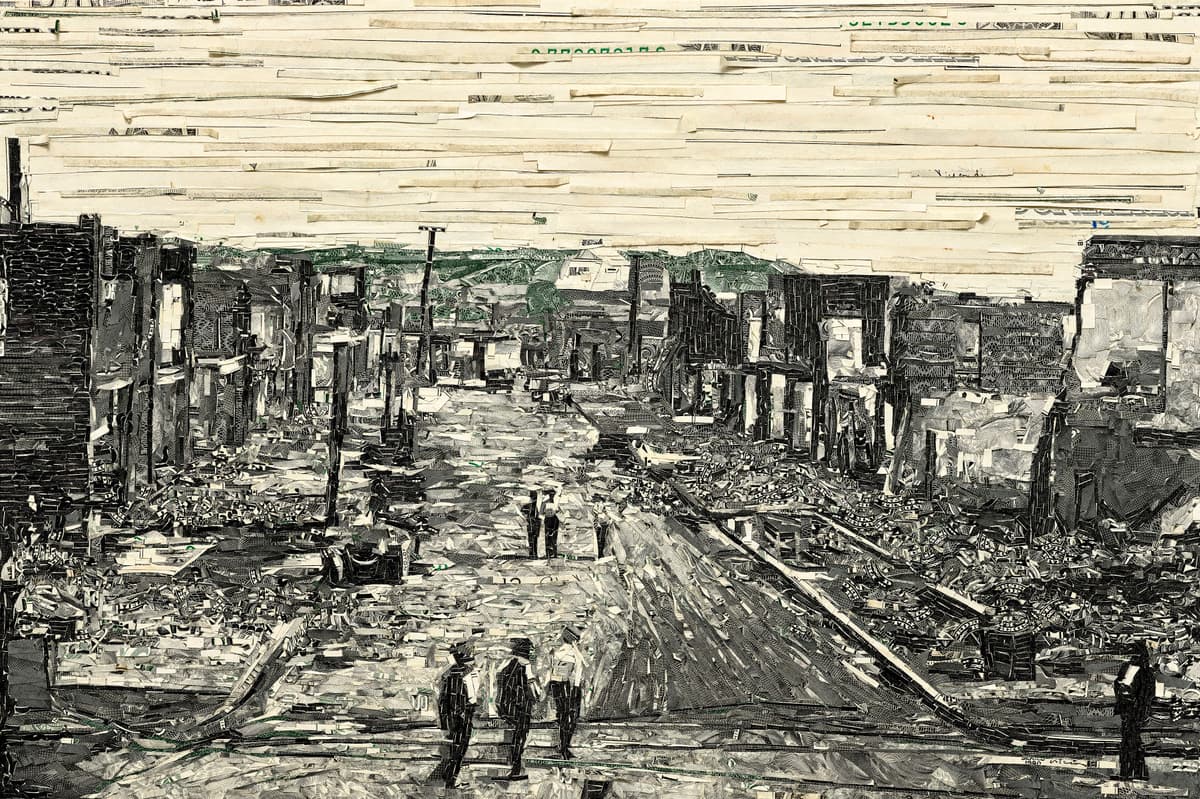

In his current show at Sikkema Jenkins, Vik Muniz repurposes iconic American images with shredded American currency. The Bald Eagle, Amelia Earhart, Sioux Chief Tashunka, and Frederick Douglas, among others, occupy the back room of the show. There is also a sobering reproduction of a historic photo which shows the aftermath of the 1921 Tulsa race riot.

As is usual in his tongue-in-cheek work, they raise questions about the very stuff our collective history is made of. Are the potent symbols of our allegedly free republic merely mirages made up of fiat currency? What is the relationship between race relations and legal tender?

Mr. Muniz has established a career recreating famous art works and photographs with unconventional and eclectic materials. He famously recreated Jean Louis David’s iconic “The Death of Marat” with trash.

A historic photo of Jackson Pollock in his studio was redone with poured chocolate, while he produced a double “Mona Lisa,” a sly reference to Warhol’s seriality, with nothing but peanut butter and jelly. His witty send ups both enshrine and subvert images from our collective zeitgeist with the recycled debris of consumer culture: mass images made with disposable or edible stuff.

Other images in this show, from his “scraps” series, show Mr. Muniz’s broader concerns along with snapshots of his private life. There is a portrait of his parents and his dog, all made with discarded and scavenged materials.

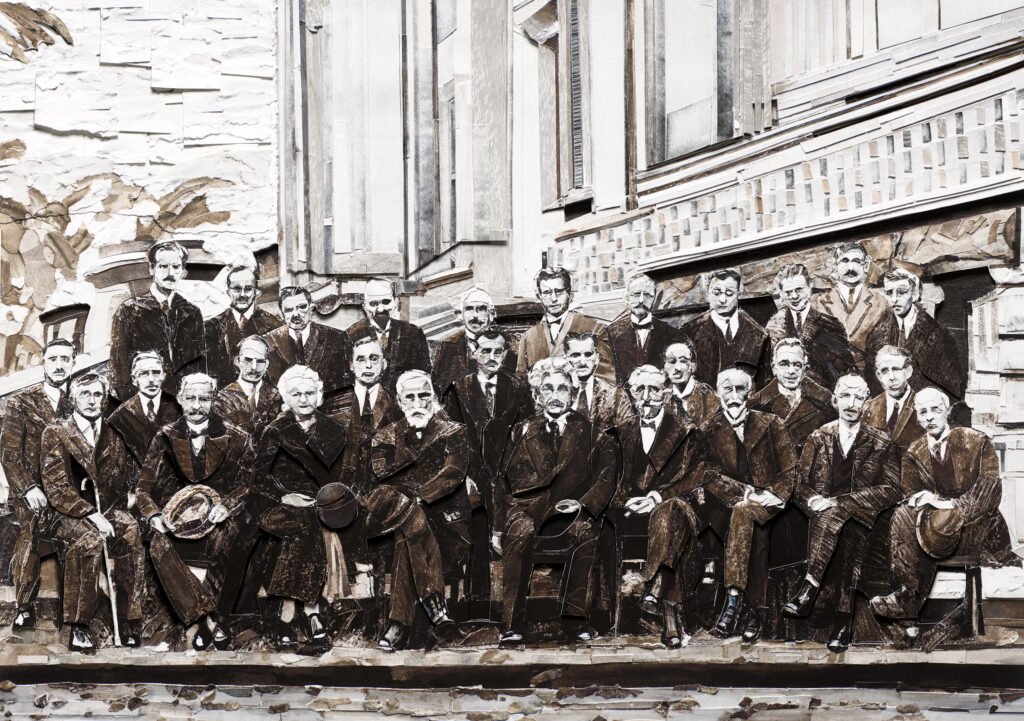

Other scrap works, such as the Hubble telescope’s awe-inspiring photo of the Horsehead nebula, or of the historic fifth Solvay physics conference, reflect a fascination with scientific issues.

This particular conference famously brought Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli and Schrodinger together to lay the groundwork for quantum theory. That this conference would fascinate Mr. Muniz makes sense given his obsession with materiality. Physics is about the basic building blocks of matter, while he is all about the building blocks of images.

Sometimes, however, the relationship between material and image is far more straightforward. His image of Tokyo, one of the world’s largest offenders in its use of single use plastic, reminds us what the metropolis is, in fact, made of.

In looking at a Muniz image something disconcerting happens. You are immediately struck by an image’s legibility yet can’t help but recognize that it is made from something else entirely. The recognition of the symbolic and the recognition of the material happen simultaneously.

It’s an understated method of telegraphing resonances between symbols and their discontents, resonances that might not otherwise come to light. Our system of currency and the way we cherish the bald eagle are seldom brought together in an image, though the connections are most decidedly there.

The process for creating these images begins in Mr. Muniz’s studio, where he starts by making rough abstracted mosaics or collages out of his chosen materials. In the case of this exhibit, scraps of different odds and ends and shredded American currency.

He then photographs these first efforts and prints them, piecing the photographic fragments into the image he is reconstituting. Often, the effect is similar to the pointillist photo realism of Chuck Close.

Mr. Muniz, who is not shy to call the Brazilian government of his childhood a dictatorship, says that he has long mastered the art of making social and political statements under a regime of extreme censorship. “Brazilians become very flexible in the use of metaphors. They learn to communicate with double meanings,” he said in a 2010 interview.

The wide range of subject matter, however, demonstrates that Mr. Muniz is very much a generalist. His process may have emerged from the bleeding edge conceptual vanguard of New York in the 1980s, where Mr. Muniz first cut his teeth, but his concern has always been mass culture and our collective and material relationship to it.

Mr. Muniz, who grew up poor in Brazil, was shot in the leg as a young man while attempting to break up a street fight. Money from his assailant — to avoid the pressing of charges — allowed him to move to New York City. He first settled at the Lower East Side, and then, at Brooklyn, where he lives and works to this day.

Mr. Muniz’s work with refuse is also an extension of his deep involvement with activism in his native Brazil. He advocates for a large underclass of poor waste pickers and recyclers known as the “Catadores,” who are collectively responsible for repurposing a huge amount of Brazil’s open landfills.

The award-winning documentary “Waste Land” stars Mr. Muniz and has made him a household name in his native Brazil. In it the artist photographs several Catadores while working alongside them, eventually transforming their portraits into classical “trash” paintings. Money from sales of these works was then given back to them, some of whom have lifted themselves out of poverty while continuing their advocacy.

Mr. Muniz’s prolific output and growing fame in his native Brazil have led some critics to criticize his work as merely clever sensationalism. The deeper and sharply ironic resonances of his work, though, are unmistakable in this show.

Beyond the very rarified concerns of what constitutes “high art,” Mr. Muniz shows himself to be what he has always been: a child from the slums of Brazil who refused to be thrown away.