Three Sets of Rare Tracks From Peggy Lee’s Many Musical Journeys Now on Offer

There can be no doubt that the best-run estate of a major legacy recording artist is that of Lee, with that of Elvis Presley also a contender.

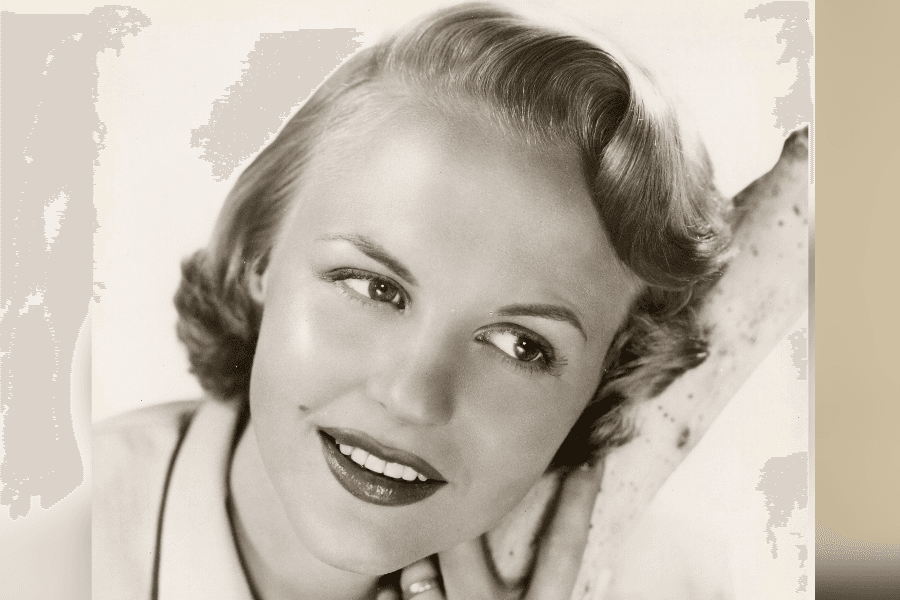

Peggy Lee

‘From The Vaults’

Available on Streaming Services

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines,” Ralph Waldo Emerson famously said, adding, “With consistency, a great soul has simply nothing to do.”

It turns out that Emerson was one of the favorite writers of a great jazz, pop, and blues singer, Peggy Lee (1920-2002), who was also a highly accomplished composer. I was thinking about Emerson’s line while listening to three sets of rare tracks by Lee that are now available on “From The Vaults.”

First off, an observation: There can be no doubt that the best-run estate of a major legacy recording artist is that of Lee, with that of Elvis Presley also a contender. The great lady’s granddaughter, Holly Foster Wells, has been doing a commendable if not spectacular job keeping Lee’s music out there; every year or so, there’s an important new release.

In the last two years alone, she gave us excellent, expanded new editions of two classic albums, “Norma Deloris Egstrom” and “I’m a Woman.” Now, Ms. Foster Wells has given us a triple treat in three separate digital collections of scarce material — a total so far of 37 tracks — that are available on Spotify, Apple Music, and other streaming services.

The first volume covers seldom-heard tracks from between 1944 and 1948, Lee’s early years as a solo singer following her career-establishing stint as a band “canary” with Benny Goodman’s orchestra. The second takes us up to the end of her first tenure at Capitol Records, in 1951, and the third covers 13 songs “making their streaming debut” that were recorded between 1951 and 1972.

It’s worth pointing out that these are all from Capitol’s vaults. Lee’s five years at Decca Records, 1952 to 1957, are not represented, but it seems likely that Ms. Foster Wells will provide us with some rarae aves from those sessions in the near future.

As Emerson exhorted, Peggy Lee was not about to be beset by a foolish consistency; to look at the rough outline of her career, we would expect her to follow the musical trajectory shared by the other female singers of her approximate generation, from Ella Fitzgerald to Rosemary Clooney, who started as big-band vocalists and graduated to become stalwart supporters of what gradually became the Great American Songbook, the music of Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, and Hollywood.

Lee’s journeys here, though, are all over the musical map; the so-called standard songbook is a starting point rather than a final destination.

Among other delights, Lee sings a great “You Can Have Him” from one of Irving Berlin’s lesser-known shows, “Miss Liberty” (1949), a lyric doused with irony in that the singer is loudly declaring precisely the opposite of what she actually wants.

Of Lee’s own songs, there’s “What More Can a Woman Do” (1944), a very old-fashioned ode of female subservience — perhaps even more than most, even though it was written by a woman. The legendary Joe Williams later recalled that he positively melted when he heard Lee sing this.

“Don’t Be So Mean To Baby” (1946) is also about a downtrodden dame, but at least it’s lightened by some playfully coy cuteness. Another lesser-known original, “Happy Music” (1950), written with her then professional and life partner, guitarist Dave Barbour, is frankly not one of her better efforts, but it’s a kind of a hip polka, and fun in a two-beat kind of a way.

Many tracks find Lee experimenting with different musical genres: “The Mill on the Floss” (1950) anticipates the folk music boom of a decade later, while Benny Carter’s “Rock Me to Sleep” (1951) is an early example of a mainstream pop singer doing a jump blues.

Other tracks point to future milestones in her own career: “”I Love You But I Don’t Like You” and “Would You Dance With a Stranger” (both 1951) are lightly swinging sambas that anticipate her breakthrough “Latin ala Lee!” album of 1960. Conversely, “Maybe This Summer” (1965) is an excellent reading of the Italian bossa nova “Estate” that makes one wish she’d done another Brazilian-style package later on.

“Once in Lifetime (Only Once)” (1950) is a sort of ersatz gypsy aria — Barbour plays a violin-like intro on his guitar — that Lee would later rework into a klezmer-style number called “I Hear The Music Now” with help from a grandiose, minor key arrangement by Gordon Jenkins.

Lee discographer Ivan Santiago discloses in his song notes here that both tunes were inspired by a relatively obscure opera overture, “Raymond or Le secret de la reine” (1851), by a prolific French composer, Ambroise Thomas. “Ev’ry Time” (1952) is an early version of a song most of us grew up hearing Jayne Mansfield sing in a madcap 1956 music biz spoof, “The Girl Can’t Help It.”

Lee also gave an early boost to two aspiring songwriters represented here. “Uninvited Dream” (1957) is relatively undistinguished Brill Building fare by a young Burt Bacharach. It’s considerably enhanced by Lee’s vocal and Nelson Riddle’s excellent arrangement, which is possibly better than the song deserves. “Didn’t We” (1969) is an early success by Jimmy Webb. At this juncture, Bacharach’s greatness was still ahead of him, but even at 23, Mr. Webb’s was already there.

Three surprising incarnations of songbook standards turn up on the third volume: “This Could Be the Start of Something Big” (1963) is a piano-centric arrangement that Billy May apparently did in homage to composer Steve Allen, an excellent pianist as well as songwriter and television pioneer.

Then there’s a highly original — and somewhat endearing — attempt to update the 1927 “Me and My Shadow” (1969); on “I’ll Be Seeing You,” she does precisely the opposite, digging deep into the inherent melancholy of this 1938 ballad and showing us that a classic song doesn’t need to be updated to keep it relevant and powerful.

In fact, Peggy Lee’s entire career shows us precisely that.