There’s More Than Meets the Eye at ‘Rear View’

The array of artworks at LGDR’s new digs on East 64th Street — the show clocks in at around 60 pieces — are diverting in their variety and quality. Do some cherry-picking, and you should walk out happy.

One might wonder whether Sir Mix-A-Lot will be attending “Rear View,” the inaugural exhibition at LGDR’s new digs on East 64th Street. The erstwhile rapper, you’ll recall, caused a stir some 30 years ago with “Baby Got Back,” his rambunctious paean to the female form. Given his predilections, Mr. Mix-A-Lot would likely sit up and take notice of the gallery’s announcement for the show, dominated, as it is, by “Etude de Fesses” (1884), a painting by the 19th-century Swiss artist Félix Vallotton.

Surely, a New York gallery wouldn’t stoop so low as to shamelessly pique our collective prurience by mounting anything even remotely lubricious? The gallery’s venue — a Beaux Arts-style townhouse that once housed the vaunted Wildenstein Gallery — wouldn’t allow for anything quite that tawdry. Having been restored to its original condition, the new LGDR is palatial. It’s a classy place.

To be fair to the organizers of “Rear View,” Vallotton is also represented with “Liseuse de dos” (1915), an image that is considerably less aggressive than “Etude de Fesses,” depicting, as it does, a young woman reading as seen from behind. It’s still a sexy picture — her shoulder is bare and its vantage point turns the viewer into a voyeur. Even at its most restrained or inelegant, “Rear View” reiterates that “no nude, however abstract, should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling.”

That quote comes from the British art historian who wrote the invaluable treatise “The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form,” Kenneth Clark. New Yorkers can decide for themselves if it’s true that when a work of art, according to Clark, fails to elicit an erotic response the corresponding piece must be considered “bad art and false morals.”

“Rear View” takes as its basis the notion of the rückenfigur, a German term that translates into “back figure.” The prototypical example of the genre is Caspar David Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (circa 1818). The good folks at LGDR rightfully emphasize the “estimable history” of the nude as it pertains to world art. The corresponding array of artworks — the show clocks in at around 60 pieces — are diverting in their variety and quality. Do some cherry-picking, and you should walk out happy.

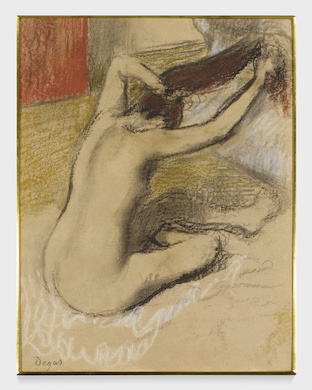

Which is to say that for every descent into immaculately limned kitsch (John Currin’s “Nude in Convex Mirror”), avant-gardist nonsense (Yoko Ono’s “Film No. 4 (Bottoms)”), or anything-goes assemblage (Michelangelo Pistoletto’s “Agenda 2030”), there are fine or, at least, signature pieces by Edgar Degas, Aristide Maillol, Rene Magritte, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, Pearlstein, George Tooker, Andrew Wyeth, and Giorgio de Chirico. A handful of contemporary artists have been asked to contribute as well, some by commission; these include Jenna Gribbon, Eric Fischl, Danielle McKinney, the estimable Seth Becker, and the eternally cack-handed Francesco Clemente.

Any instructor of drawing will tell you that the back of the torso is among the most difficult portions of the anatomy to draw, given its relative paucity of pronounced features. In that regard, special attention should be made to a quartet of works-on-paper by Paul Cadmus, wherein the male back is brought to nuanced realization by the adept use of cross-hatching. Jared French is similarly attentive to the sloping contours of the back in “Prose” (circa 1948), a Surrealist reverie delineated through pointillist means.

Barkley Hendricks’s “Pat’s Back” (1968) evinces the streamlined realism for which he is rightly celebrated (and shamelessly imitated), and reminds one that a dozen or so of his portraits will be on display alongside those of Bronzino, Van Dyck, and other stellar mainstays at the Frick Collection come this fall. Something to look forward to.

Domenico Gnoli, a painter little known on these shores, would be a good match for a similar comparative installation. Gnoli’s two sizable canvases, “Back View” (1968) and “Curly Red Hair” (1969), owe as much to the Renaissance as they do to Surrealism and Pop Art. That, and the pictures bring a punning wit to “Rear View” that will, I think, amuse most New Yorkers even as they don’t quite fit the predilections preferred by Sir Mix-A-Lot. You can’t have everything.