Theaster Gates, Using the Brute Vocabulary of Things, Confronts Viewers at White Cube

As a functionalist and a formalist, his medium is his entire message.

Theaster Gates: ‘Hold me, Hold me, Hold me’

White Cube Gallery, 1002 Madison Avenue, New York, NY

January 26 – March 2, 2024

“Heavy” is a word that comes to mind when thinking about Chicago artist Theaster Gates. His sculptures, installations, and paintings, often made with reclaimed construction scraps and roofing material, have a way of singularly concentrating their mass and impact. You do not look at a work by Mr. Gates so much as you are confronted by it. Mr. Gates has developed a language using the brute vocabulary of things, producing works that can devour a room with their deafening silence.

Mr. Gates’s new show at White Cube probes the connections he mines between his lived experience and his materials. As a functionalist and a formalist, his medium is his entire message.

He is also an activist and a poet. Conducting a gallery walk-through of the show, Mr. Gates, who carries himself with the dignity of a former boxer, spoke in a voice that sometimes quivered with emotion. “Let’s gather around the piano” he said, taking that assembled crowd to an upright piano sitting atop a thick chunk of reclaimed marble plinth. It is entirely swathed in torch down roofing and sealed with silver bitumen paint.

Titled “Sweet Sanctuary, Your Embrace,” It’s a formidable sculptural object that Mr. Gates admits is a standing paradox. His late father, who was a roofer by trade, also loved music. He then explained how the piece embodies his desire to “hold on” to the memory of his deceased father even as he destroyed the piano’s original purpose.

It is also a tribute to Donny Hathaway, to whom his father listened often. Hathaway succumbed to paranoid schizophrenia while recording a series of duets with Roberta Flack, and their song “Be Real Black for Me” inspired the sculpture. A line from the song, “In my head I’m only half together…so hold me, hold me, hold me,” also inspired the title of the show.

As Mr. Gates explained, “I’m sealing this piano like a roofer, against leaks, just as my father would have done in his trade. But I’m also Donny Hathaway, using music to try and seal himself away from the demons in his mind. Just as I use my art to keep myself ‘half-together.’ It’s also me doing my best to seal in and hold on to the memories of my late father, which are already fading…”

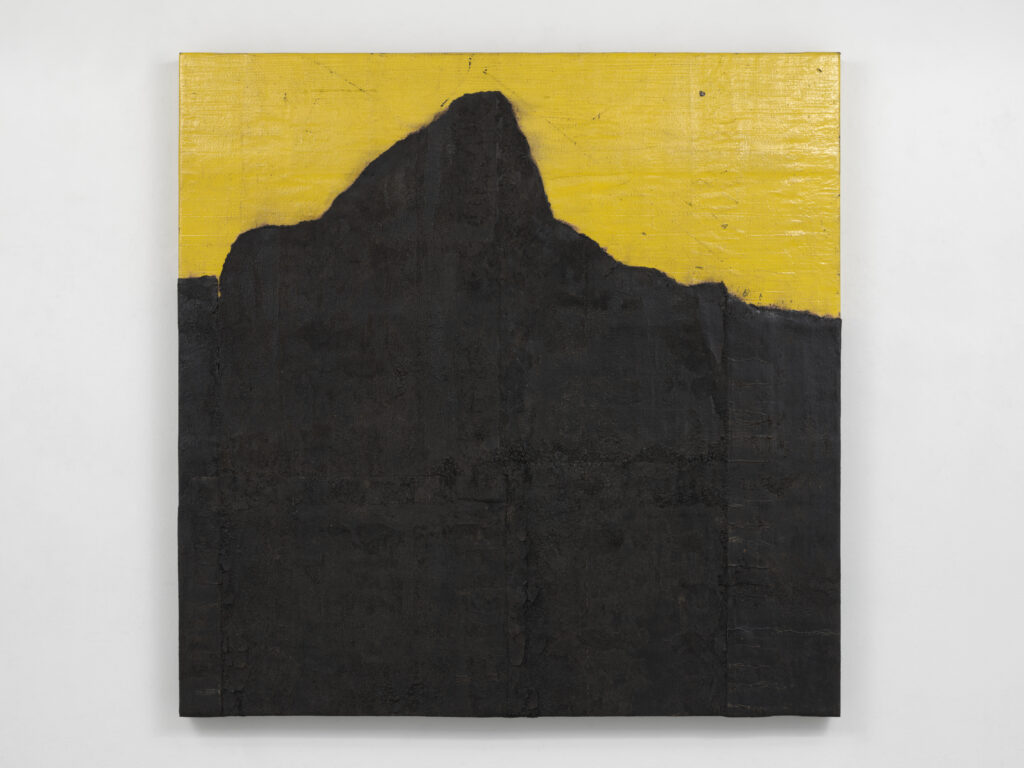

This theme continues with the other paintings in the room, such as “The Only Portrait I’ll Ever Know,” or the twin paintings “Hill” and “Plateau.” Though the works speak the language of abstraction handsomely and fluently, they have added allegorical heft brought by Mr. Gates’s uniquely organic methodology.

This richly layered dialogue between material, process, and lived experience is the fulcrum on which Mr. Gates’s art continuously hinges. His personal narrative, the experience of his fellow Black Chicagoans, his formalist and poetic ruminations on form and space: these all meld into the Möbius strip that is his practice, a loop that feeds itself.

Black history is an essential part of it. The second floor is a devoted tribute to publisher John Johnson, who is the original founder and publisher of Ebony and Jet magazines. Consisting of salvaged wall paneling taken from the Johnson’s corporate headquarters, Mr. Gates made the installations “to preserve the dignity of Black entrepreneurship.” Cardboard boxes with issues of the magazine form part of the installation. Taken as whole, it gives off the aura of a 1970s office suite, with an added note of melancholy.

Trained in both urban and religious studies, Mr. Gates began taking pieces of decayed infrastructure such as lathing, counter tops, and strips of flooring and incorporating them into his artwork early on. As his reputation grew, profits from sales funded larger philanthropic projects, such as the transformation of derelict South Side buildings into community and cultural centers. As such, Mr. Gates is counted among members of the “social art” movement.

He has since become a force in the contemporary art world, helming a considerable organization dedicated to both art and urban renewal. This has led to cynical claims from some corners that he represents art as virtue signaling entrepreneurship, a way to repurpose derelict infrastructure for art profit.

This is to miss the point entirely. As is evident from the viscerally impactful works in the show, Mr. Gates is deeply, if not soulfully, invested in his mission of art as transmutation and renewal. He does not choose his materials lightly, nor does he deploy them without thinking through their provenance. The thought and labor required to do so is obviously intensive.

“These materials are anything but free.” He told the room with all the solemnity of a Baptist preacher. “They are bought and suffered for.”