The Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers: New Books Focus on the Comedy Teams’ Odd Brothers Out

The biography of Shemp Howard works to correct the record set largely by Moe Howard, while Zeppo Marx is shown to have been much more than an eternal fifth wheel and a punchline.

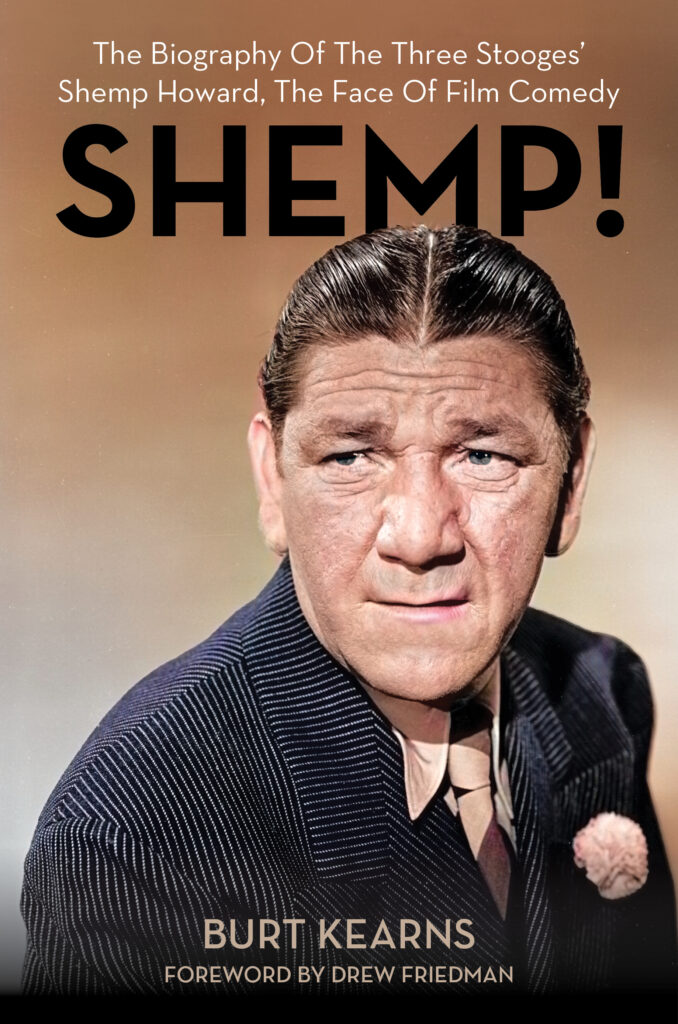

‘Shemp!’

By Burt Kearns

Applause Books, 280 Pages

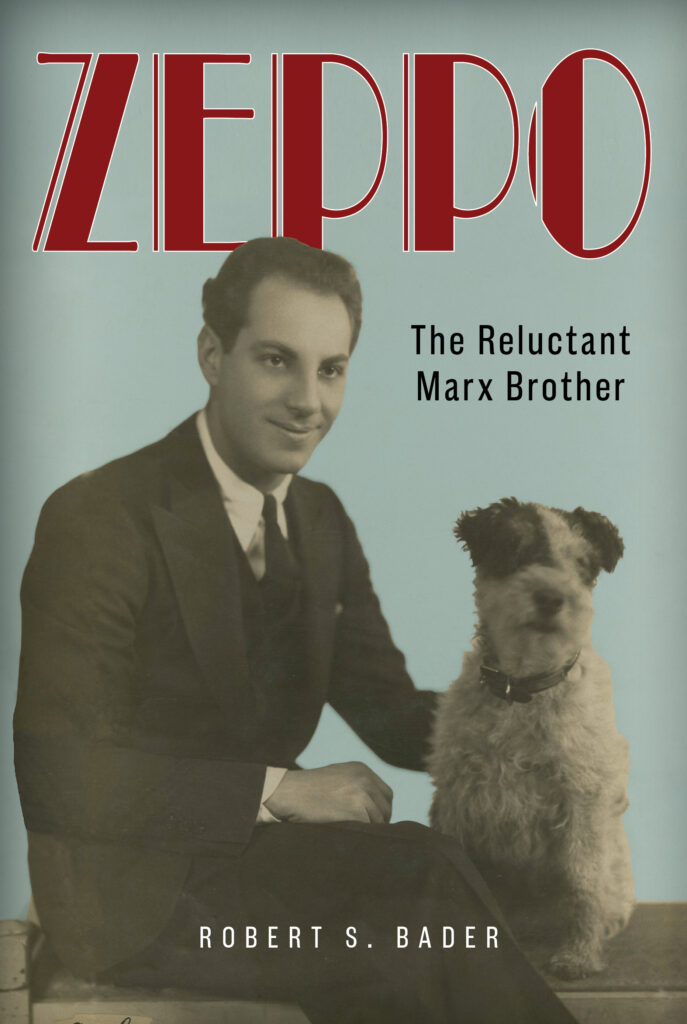

‘Zeppo: The Reluctant Marx Brother’

By Robert S. Bader

Applause Books, 368 Pages

With the near simultaneous appearance of “Shemp!” and “Zeppo: The Reluctant Marx Brother,” a classic comedy maven could wonder why a biography of Harry Ritz might not have also been published. A triumvirate of yiddishe brother acts: The mind boggles.

Then again, the Ritz Brothers haven’t left a dent in the popular imagination, while the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers are performers who, in one form or another, persist as public figures to this day. The two new books focus on the odd brothers out in each team.

Shemp Howard (1895-1955) — by some lights, “the ugliest man in Hollywood” — started his career not as a stooge but as a boob. As detailed in Burt Kearns’s exclamatory paean, the first public notice of Howard as a performer was in the April 16, 1924, edition of Variety, where he was listed as one of “two boobish looking saps.” The other sap was Shemp’s brother Moses Hurvitz, now known to history as the bullying and indomitable Moe.

The “stooge” was an established theatrical trope by the mid-1920s, being a member of an ensemble that would pop up in a skit or be planted in the audience to interrupt or augment the proceedings — invariably to the benefit of the lead. Moe and Shemp were stooges to Ted Healy, a singer and comedian who was a significant commercial draw both in vaudeville and on the Broadway stage. Healy’s brand of knockabout comedy would be a decisive factor in shaping the stage and movie schtick of the Howard brothers.

Mr. Kearns sets out to right the historical record set largely by Moe Howard. The author allows that Howard’s memory at the time of the writing of his autobiography may have been affected by the vagaries of age. He also intimates that Moe wasn’t beyond embellishing facts or doling out calumnies. In terms of germinating their roustabout act, Mr. Kearns insists it was Shemp who was the model, the star, and the man who first spied the comic violinist and future Stooge, Larry Fine. Moe’s attempts to claim the career highground were vindictive in intent, if not necessarily in word.

Once he split from the Stooges in 1932, Shemp had a good thing going as a character actor. He rarely stopped working and though comedy was his forte, he was given a few dramatic roles. The high point of the solo career came at Universal Pictures, in which Shemp held his own against comedic scene stealers like W.C. Fields, Lou Abbott, and Mary Wickes. When younger brother Jerome was felled by a stroke and could no longer perform as Curly, Shemp rejoined the Stooges to memorable effect in a series of increasingly ragtag comedies.

Howard died in a taxi on the ride home after attending a prize fight. The doctors listed the cause as a heart attack; the family insisted it was a stroke caused by a blood clot in the brain. Mr. Kearns suggests that Shemp’s death was accelerated due to physical stress caused by an accumulated 40 years of being slapped, bopped, and poked — and so, too, were the deaths of Curly and Larry. A chapter titled “Who Killed Shemp?” is prefaced by a comment about Moe “carrying around some sense of guilt.” Fans of the comic trio have been given much to moot over with Mr. Kearns’s biography.

If Shemp has become the focus of an enthusiastic, if highly quixotic, fanbase, then the popular legacy of Zeppo Marx (1901-79) is that of an eternal fifth wheel and a punchline. As part of the Marx Brothers, Zeppo was a distant satellite around which careened the antics of Groucho, Chico, and Harpo. The youngest of the bunch — Zeppo was born a good decade after his siblings — he was drafted into the act after another brother, Gummo, was inducted into the Army. The machinations of a prototypical stage mother, Minnie Marx, could not be denied.

Author and filmmaker Robert S. Bader has spent more than a few years dedicating himself to all things Marx. He wrote “Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage” in 2016; in 2022, he was co-author of the autobiography of Susan Fleming Marx, “Speaking of Harpo,” and put together a PBS American Masters film, “Groucho and Cavett.” Mr. Bader insists that the blandest brother deserves his own bio because “if the story of the Marx Brothers is a triumphant showbiz tale, Zeppo’s is a dimly lit film noir based on a gritty crime novel.”

Just how seedy, seamy, and underhanded was the man born Herbert Manfred Marx? In an interview with the Observer, Mr. Bader mentions that Zeppo “never killed anybody, as far as I know.”

Young Zeppo proved adept at hooliganism — jimmying the stray car for a joyride was but a moment’s work for the mechanically minded adolescent. He had a short-temper and was prone to fisticuffs — a tendency Zeppo didn’t outgrow after becoming a public figure. Even as old men, Groucho, Chico, and Harpo would open the newspaper to read about Zeppo’s latest high-profile scrap, and they weren’t happy about it. Nor did they like reading about Zeppo’s repeated appearances in front of grand juries weighing mob-related doings.

Zeppo kept company with more than a few disreputable characters and, as such, had some pull. After leaving the Marx Brothers, he became a Hollywood agent renowned for giving has-beens a second chance and newbies impressive shots at stardom: Among his finds were Fred MacMurray, Ray Milland, and Barbara Stanwyck.

All the while he took to playing serious games of bridge, possibly setting up a burglary ring, and gambling — lots of gambling. Harpo’s son, Bill Marx, wrote that Uncle Zeppo “wasn’t into the action to ‘win’ the contest. He just wanted to beat the crap out of you.” There have been more lovable rogues.

Marx led a far-reaching life. Should you be in need of a new party game, replace “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” with “Three Degrees of Zeppo Marx.” You will, I guarantee it, end up at some perplexing endpoints, including gangsters Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, and Bugsy Siegel; Vice President Spiro Agnew; pop crooner Frank Sinatra; the advent of roll-on deodorant; and — no, I’m not kidding — the Enola Gay.

Mr. Bader has done his due diligence in terms of research but doesn’t make a fetish of the facts. That, and he writes with a sly sense of humor. How close does he come to illuminating a man who remained an enigma to his brothers, his wives, and his two sons? “Narcissism, self-indulgence, and selfishness,” Mr. Bader concludes, “permeated all aspects of Zeppo’s life after he left the Marx Brothers.”

Say this for Zeppo: the five films in which he co-starred with Groucho, Chico, and Harpo are considered their finest, and no less an eminence than Cary Grant extolled Zeppo’s virtues as a straight man and fashion plate. Grant’s opinion will, I predict, remain in the minority for readers of this exemplary book about a difficult and driven man.

Correction: 1979 was the year Zeppo Marx died and 2016 was the year Robert S. Bader wrote “Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage.” The years were incorrect in an earlier version.