The Notebooks of Charles Burchfield, an Heir of Thoreau and Whitman, Showcase the Painter’s Metaphysical Longings

Though his work is included in important collections and has been the subject of museum exhibitions, Burchfield doesn’t carry the high profile of his friend Edward Hopper.

“We have been amusing ourselves the last few evenings telling the temperature by counting the notes of the tree-crickets” wrote the American painter, Charles Burchfield, on September 1, 1938. “The formula,” he mentions in a parenthetical comment, is “the number of notes in 13 seconds, added to 42.” Can someone from the American Meteorology Society confirm or deny this methodology? Burchfield found it “remarkably accurate.”

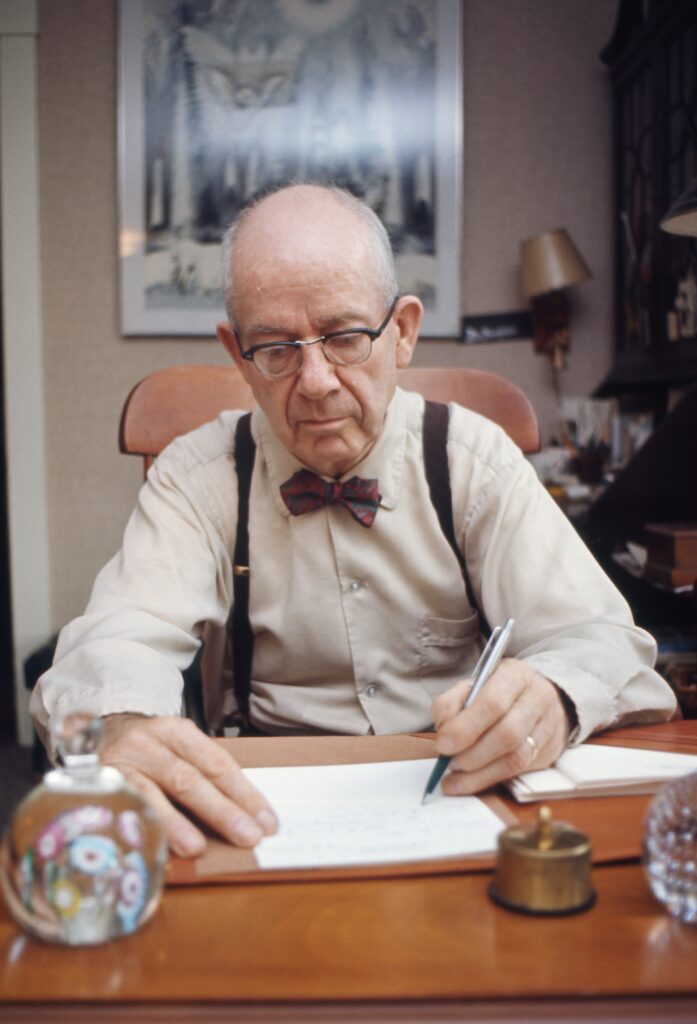

The above is an excerpt from the artist’s 72 notebooks, a lifelong pursuit that would eventually number 10,000 pages. In 1993, the State University of New York at Purchase published “Charles Burchfield’s Journals: The Poetry of Place,” a book in which a SUNY Buffalo professor of English, J. Benjamin Townsend, culled the entries to a mere 740 pages.

The poet Ben Estes has gone a step further by editing the count to 174. The resulting volume, “The Sphinx and the Milky Way; Selections from the Journals of Charles Burchfield,” published by the Song Cave, will neither tax your bookshelf nor burden one’s backpack. It’s a welcome effort.

That is if you’re familiar with Charles Burchfield (1893-1967). Though his work is included in important collections and has been the subject of museum exhibitions, Burchfield doesn’t carry the high profile of his friend Edward Hopper.

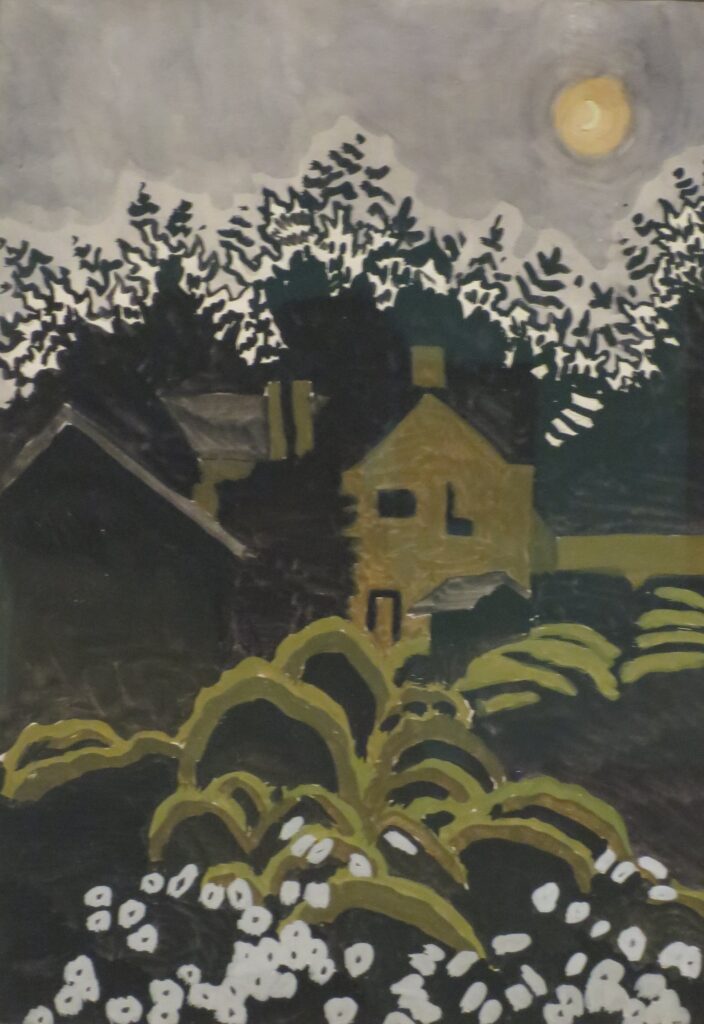

Though they shared a certain ascetic purview, Burchfield was given to more metaphysical longings based upon an abiding communion with nature. He was heir to the essayist Henry David Thoreau, the naturalist John Burroughs and the poet Walt Whitman. “I want to praise and exalt nature,” Burchfield noted, “as [Whitman] has done in ‘Leaves of Grass.'”

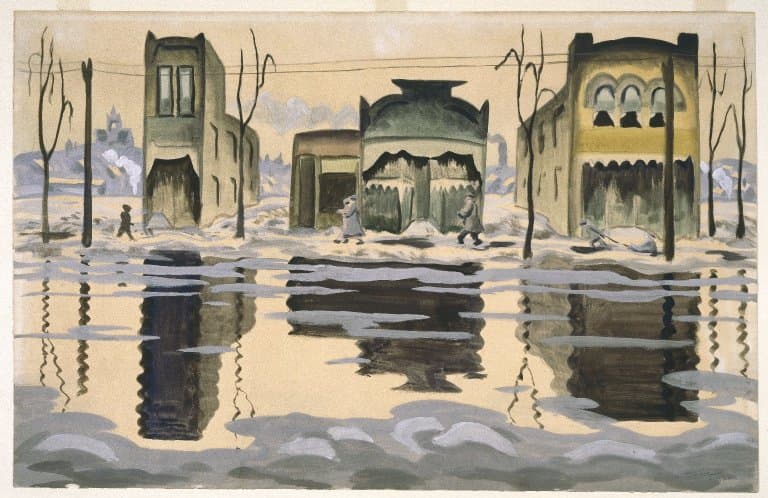

In her introduction to “The Sphinx and the Milky Way,” the Head of Collections at Buffalo’s Burchfield Penney Art Center, Nancy Weekly, writes of how “Burchfield lived at the cusp of change, as 19th-century idealism faced rapid industrialization.” Though he saw the effects of encroaching urbanization and even mulled traveling to Mars — “it will be a glorious human achievement, but I hate it!” — Burchfield maintained a guileless wonder.

He could be entranced by a single leaf from an oak tree or the intellectual machinations of a tiger-swallowtail butterfly. “A lovely creature,” he wondered, “What goes on in his brain?” The empathy within Burchfield’s observations can catch the reader up short.

Yet, then, there are bad days. Burchfield was prone to “soul destroying” depression, frustrated by having to work in order to support his art and equivocal about organized religion, though he did ultimately join the Emmanuel Lutheran Church — largely, one feels, at the behest of his beloved and devout wife, Bertha.

He was often riddled with self-doubt and leery of theorizing: “The ever recurrent idea that art should speak to the mass of the people … [is] dangerous to the artist who allows it to permeate his consciousness even to a small degree.” Burchfield would likely bristle at the inclusive prerogatives of our current crop of tastemakers. “One must always be on one’s guard.”

Burchfield’s journal — or, at least, the samples excerpted here — is notably bereft of humankind. True, the stray person is mentioned — “B” shows up regularly, his children are glanced upon, and a newspaper boy is bemoaned because of his “unutterably horrifying” transistor radio — but the natural world predominates.

In that regard, the entries are very much like his notably unpeopled paintings, examples of which punctuate the text. What else might you expect from a man who pondered “the agonizing mystery of Infinity” upon considering pussywillows, dandelions, and hemlock?

“The Sphinx and the Milky Way” throws a divulging and, in the end, amenable light on Burchfield’s achievement and will prove vital to any serious art library.