The Enduring Power of a Master of Refined Understatement, Isamu Noguchi

Shows at London and New York explore different aspects of this unique artist’s masterful 20th-century career, which spanned America and Japan and included sculpture, installation, design, and landscape architecture.

Isamu Noguchi

‘Subscapes’

The Noguchi Museum

Long Island City, New York

‘This Earth, This Passage’

White Cube Mason Yard

London, U.K.

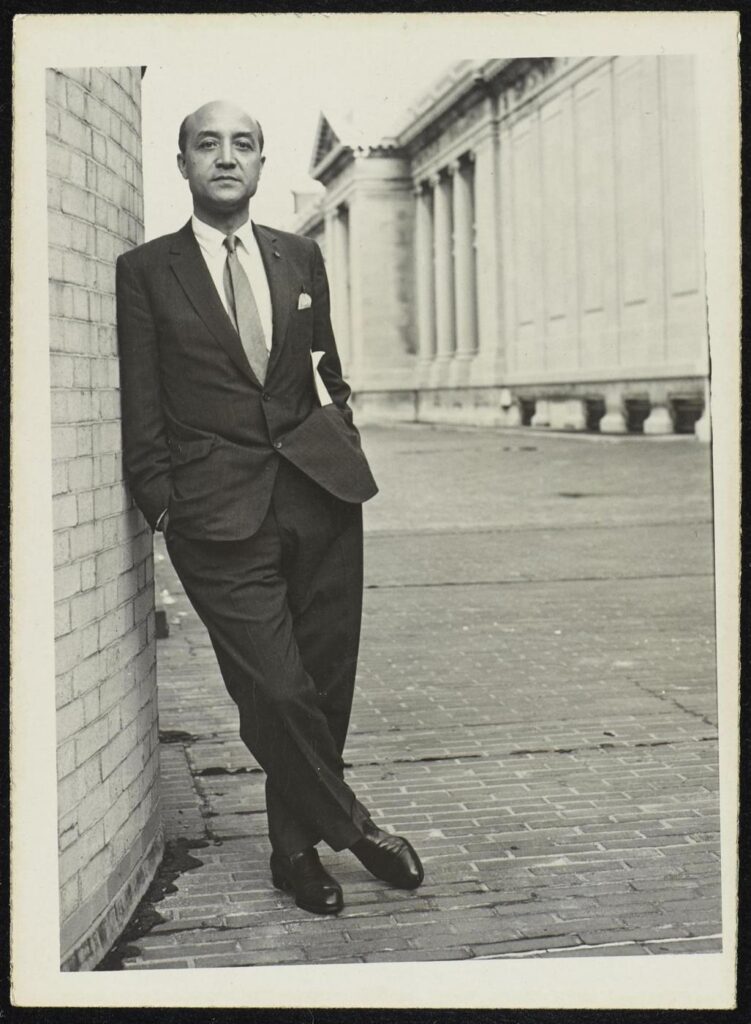

It must be stated that I feel a deep personal connection to the work of Isamu Noguchi. I never knew him personally, of course, but my mother Shinko, a well-known California ceramist in the traditional Japanese style of Shoji Hamada, declared him her favorite sculptor. Known for his rough-hewn stone, metal, and wooden forms, Noguchi had mastered a quality she called Shibui, the Japanese aesthetic of refined understatement.

Noguchi is currently the subject of two shows, one now on at the Noguchi Museum in Queens, titled “Subscapes,” and another opening Friday at London’s White Cube gallery, “This Earth, This Passage.” Both shows explore different aspects of this unique artist’s masterful 20th century career, which included sculpture, installation, design, and landscape architecture.

“Subscapes” explores Noguchi’s continued fascination with negative and “unseen” spaces. Noguchi’s forms have always had the uncanny ability to hold space in intuitive and novel ways, molding the emptiness around them even as they boldly proclaim themselves.

“This Earth, This Passage” at White Cube was curated with an eye to Noguchi’s ideas surrounding embodiment — such as his set design with Martha Graham — showing how his conceptions of the body have been central to his work across many stylistic iterations.

Understatement doesn’t quite cover the enduring power of Noguchi’s work, which grew organically out of a struggle with his materials. He consistently sought to unearth an essential quality in his sculptures, a quality he referred to as “gravity.” His work also grew out of his displacement between two cultures, as an artist who never truly felt at home in either America or Japan.

Noguchi’s aesthetic mission began with a struggle against his own imitative ability. As a young pre-med student, he attended an evening sculpture class at Columbia, and was immediately smitten. He showed an incredible facility with representation and was able to recreate nearly every sculptural style.

Dissatisfied with this surface engagement, Noguchi repaired to Paris. There, he worked with Constantin Brancusi, a gruff Romanian whose mission was to uncover an elusive non-representational essence of form. Noguchi would work with him for six months as the only studio assistant he ever accepted.

Noguchi was extremely fortunate in the connections he made. Early on he developed a life-long friendship with R. Buckminster Fuller, whose far-flung futuristic ideas would influence Noguchi’s later suggestions for landscape and garden installations, some of which are now being recognized as an early precursor of land art. He was also associated with the New York School and was friendly with Willem De Kooning.

The critic Clement Greenberg, though, was dismissive, referring to Noguchi’s early work as too refined and too tasteful. The comment stung, and Noguchi retreated to Japan, as he would many times throughout his life, to feed from Japanese aesthetic sources, such as Kyoto’s rock and gravel Zen gardens. While there, his avant-garde New York sensibilities would chafe against Japan’s deeply traditional aesthetics, where his famed paper sculptural lamp ideas were dismissed by a Japanese manufacturer as “too bizarre.”

I am sadly not at London for the White Cube show, but I was prompted to visit Noguchi’s spiritual home at the Queens Museum, which is the only museum set up by a living artist at New York City to house his own artistic practice.

Visiting the Noguchi Museum last Saturday, I was reminded of the profound influence he has had on my thinking about form and space. He was central to my decision, upon my mother’s death, to forgo a traditional carved headstone and source a large, natural piece of granite to mark her resting place instead. I’m sure they both would have approved.

There is a primordial voice, a natural beingness inherent in natural materials that Noguchi addressed. Situating his whole life between New York’s art world and Japan, he stands as a unique embodiment of both artistic cultures.