Robert Storr, the Bad Boy of Curating, Is Back, With a Large Group of Misfits, To Induce ‘Retinal Hysteria’

The show runs the gamut from murkily abstract, to the savagely cartoonish, to the downright surreal.

‘Retinal Hysteria,’ curated by Robert Storr

Venus Over Manhattan

39 Great Jones Street & 55 Great Jones Street, New York, NY

Until January 13, 2024

Robert Storr may have retired recently, but he has kept his reputation as the bad boy of curating.

A painter, academic, and curator, Mr. Storr has had a storied career at the highest echelons of the art world. Among his many positions at leading institutions, he has served as senior curator at the Museum of Modern Art, was dean of Yale’s school of art, and was the first American-born curator of the Venice Biennale.

As a critic Mr. Storr came to prominence 20 years ago with his landmark catalog essay for a show of new art at the Stedelijk museum in Amsterdam, titled “Eye Infection.” Curated by Jan Christian Braun, Storr championed the show’s jabs at the canons of ‘good taste’ in contemporary art as he saw them.

With art that was often difficult, confrontational, or downright grotesque, Mr. Storr’s essay introduced American audiences to works that presented a distinct sort of challenge. It wasn’t so much a protest against good taste as it was a rallying cry to not fall into aesthetic complacency.

Mr. Storr also championed art that picked and worried at areas of human life which were frankly uncomfortable. Mr. Storr looks for artists who actively plumb the murkier areas of human experience, consequences be damned. The results are always interesting, if not, occasionally, downright disturbing.

“Retinal Hysteria,” which is currently at the Venus Over Manhattan gallery on Great Jones Street, presents itself as a sequel of sorts to the landmark show 20 years ago. This time, the show has rebooted itself with tongue in cheek sensationalism. The accompanying show text is printed in lurid tabloid format — the National Enquirer comes to mind — its headline blaring “Storr to Purists: Kiss My Aesthetics”.

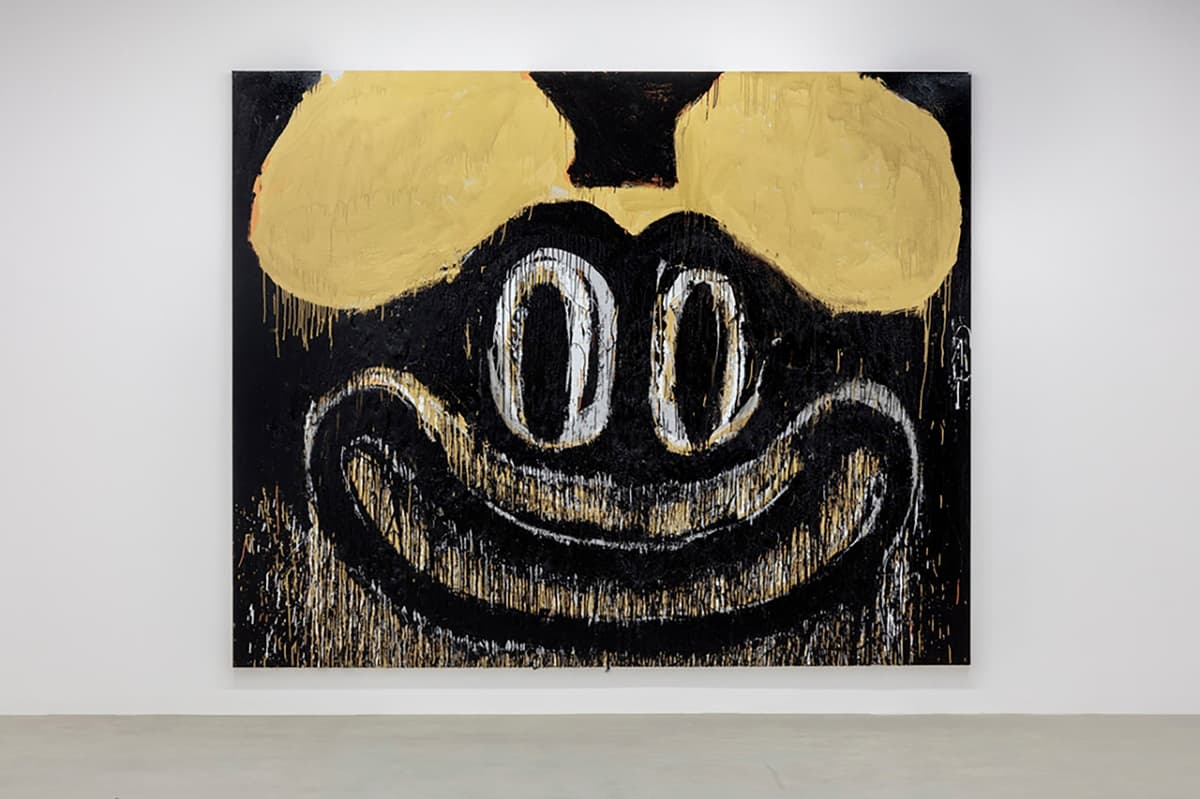

As promised, the bulging line-up of 45 artists is anything but pure. The show occupies both gallery spaces on Great Jones Street, running the gamut from murkily abstract, to the savagely cartoonish, to the downright surreal. Mr. Storr doesn’t disappoint eyeballs that are looking for a jolt.

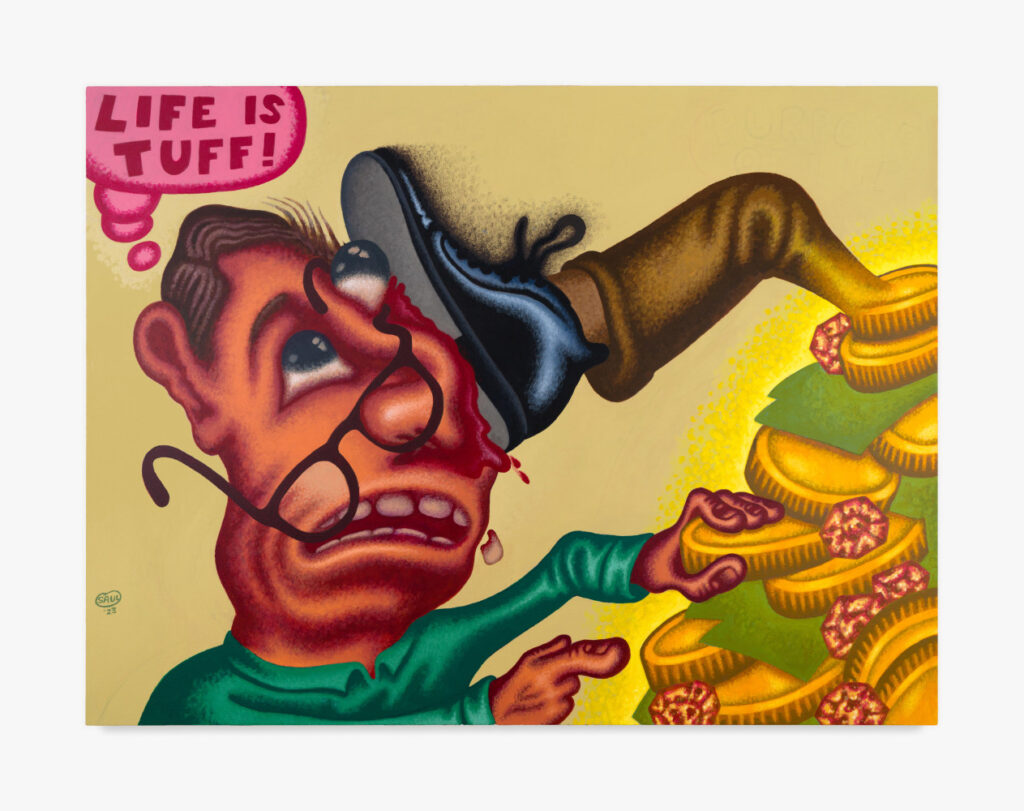

Some artists from the first show have returned, such as the cartoonishly ominous Peter Saul. His painting shows a man reaching for a gold coin that has magically sprouted a leg kicking him in the face. Ed Paschke’s “Accordion man” shows us an accordion player with a sinister grin, oversized hands, and an oddly shrunken head. David Lynch comes to mind.

Mr. Storr also features extremely well-known artists expressing themselves in less than characteristic ways. Louise Bourgeois, for instance, provides three rare drypoint etchings of contorted female figures, but in bright blue, a departure from her mostly monochrome work. Art Spiegelman provides several amorphous pages of doodles, which include meditations on Superman and fascism.

Most astonishing is a mural-sized ink drawing by Kara Walker, “Epoch Fail,” which is as roughly painted and hyper dramatic as her iconic silhouettes are coolly ironic. It portrays a cloud of unruly and bloodied babies exploding out of a central mother figure. The racial subtext, always strong in Ms. Walker’s work, suggests generations born into endless turmoil.

If there is any critique of the show, it is that it is too much. 45 artists is an astonishingly large group of misfits to corral into two rooms. It clashes and overwhelms, to the point that hysteria seems to be an actual state the show aims to instill. Yet Mr. Storr has an eye for work you can’t look away from, which is to say that almost all of it is compelling.

More catholic critics have accused Mr. Storr of rebellion for rebellion’s sake. Yet the uncomfortable and downright grisly have been a part of great art at least since Goya painted Saturn horribly devouring his son, or Grünewald’s ghoulish but brilliant “Pietas.”

We might also remember Picasso grafting African masks onto the filles de joie of Avignon, or Bourgeois’s giant and creepy sculptural spiders. At the show’s opening, Mr. Storr frankly stated that having an affinity for an artwork is hardly the sturdiest measure of its worth.

“Like is a relatively weak emotion to have in relation to art” he said. “There is work in this show that I don’t necessarily like, that is irritating, provocative, and unsettling. But I have noticed it, and that signals to me it is substantial and strong.”

_____________

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the circumstances of Mr. Storr’s rise to prominence as a critic.