NYU’s Grey Art Museum Invites Us To ‘Make Way’ for a Most Notable Parisian Art Dealer, Berthe Weill

For anyone interested in early Modernism, ‘Make Way for Berthe Weill’ is not only informative but rife with sterling and sometimes revelatory works of art. It’s an energizing exhibition.

Directly before entering a newly opened show at NYU’s Grey Art Museum, “Make Way for Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde,” viewers encounter a small picture of a big personality, a 1933 portrait of the exhibition’s namesake by a Czech artist, George Kars. Surrounded by an abundance of casually stacked canvases, Weill is depicted as bug-eyed and stolid, her black raiment and erect carriage connoting immovability as much as eccentricity.

Could this be someone who would title an autobiography “Pow! Right in the Eye”? You bet it is.

“Make Way for Berthe Weill” includes additional portraits of the art dealer affirming the case made by Kars. Édouard Goerg pictures Weill twice: in a freeform pen-and-ink drawing, she is seen in the company of an overbearing “art lover”; the second time, in oils, she’s in the presence of a similarly comported figure. In both cases, Weill has been shuttled to the periphery of the compositions, suffering the arrogance of capital and, if we take a cue from curator Anne Grace, the hubris of art critics.

Weill (1865-1951) had choice words for the latter. In a 1927 interview with the journal Cahiers d’Art, she harrumphed that critics “can only write nonsense.” Given that Weill was on good terms with the critic and collector Adolphe Basler — the gargantuan creature whose lumpish backside has been immortalized in “Portrait de Mademoiselle W” (1926) — perhaps it’s Georg’s enmity, more than Weill’s, that’s at the fore. Still, it’s not too much to conjecture that a woman who described herself as “stiff-necked, forbidding, and … difficult” has been accurately represented.

Via Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Annie White Townsend bequest

The first English-language translation of “Pow! Right in the Eye” was published in 2022 under the stewardship of the Grey Art Museum director, Lynn Gumpert, and the late art dealer Julie Saul. The current exhibition has been organized by Mses. Grace and Gumpert, along with the collections administrator at Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie, Sophie Eloy, and the director of the Berthe Weill archives, Marianne Le Morvan. For anyone interested in early Modernism, “Make Way for Berthe Weill” is not only informative but rife with sterling and sometimes revelatory works of art. It’s an energizing exhibition.

Weill was born into a Jewish family of modest circumstances at Paris in the city’s 1st arrondissement. Her father was a ragpicker; her mother, a dressmaker and housewife. Weill was the fifth of seven children and sickly by nature. The Weill kids all went off to work at an early age. Berthe was a teenager when she began apprenticing with art dealer Salvator Mayer.

Upon Mayer’s death in 1896, Weill opened an antique store with funds provided by her family and Salvator’s widow, Rachel. Business was rocky for reasons that were both economic and cultural. When she displayed a Henry de Groux painting, “The Mocking of Zola” (1898), in her storefront window as a response to the Dreyfus Affair, Weill suffered the taunts of not a few Parisians. She soldiered on: Weill was made of stern stuff.

Which isn’t to say she didn’t have help. Among her early benefactors was a Catalan industrialist, Pere Mañach, who would aid in renovating the young businesswoman’s living space on 25 Rue Victor-Massé into a working gallery. Mañach also tipped off Weill to the drawings and paintings of a young Spaniard by the name of Pablo Picasso, whom she subsequently provided with his first exhibition opportunity at Paris. The Weill family wasn’t thrilled with Berthe’s career plans: smart businesspeople rarely make art their trade. Hindsight being what it is, Weill was amazingly prescient in her tastes.

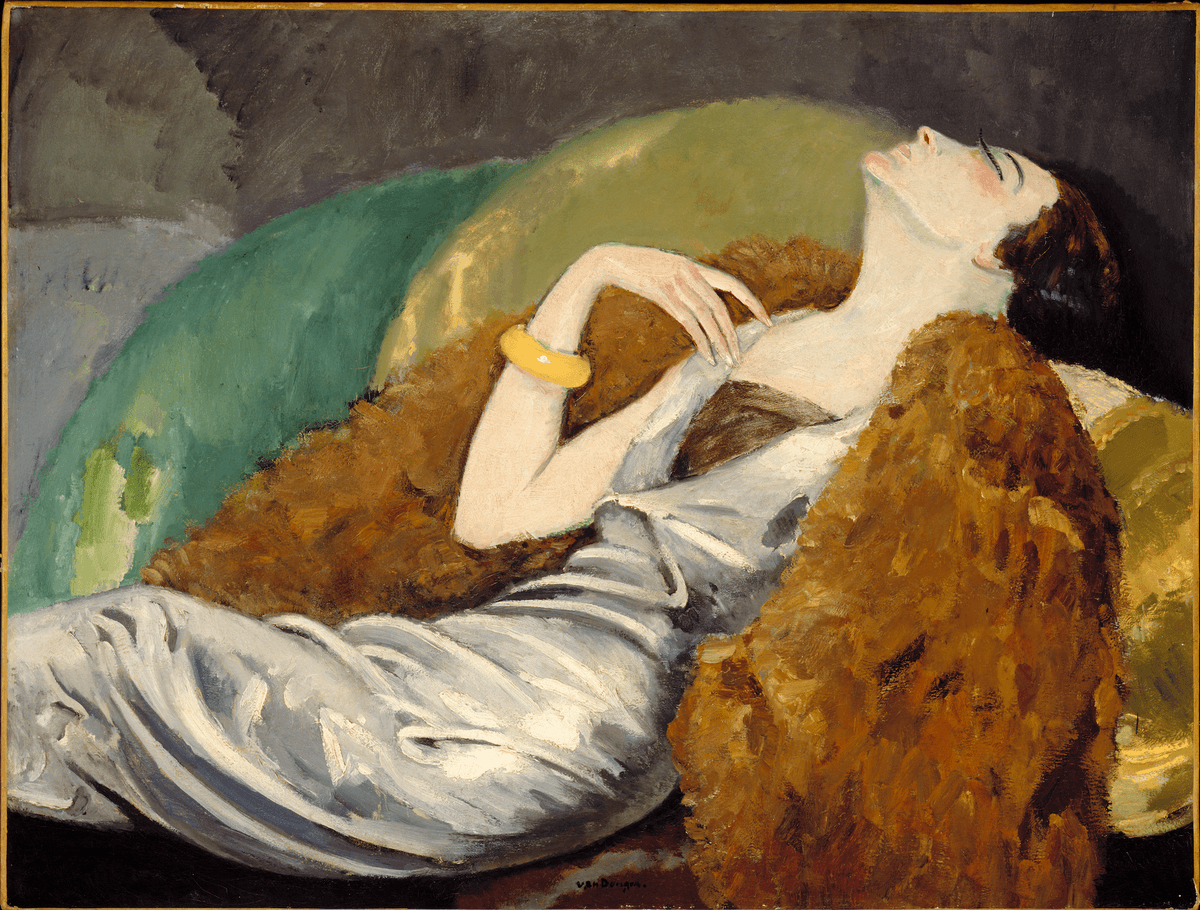

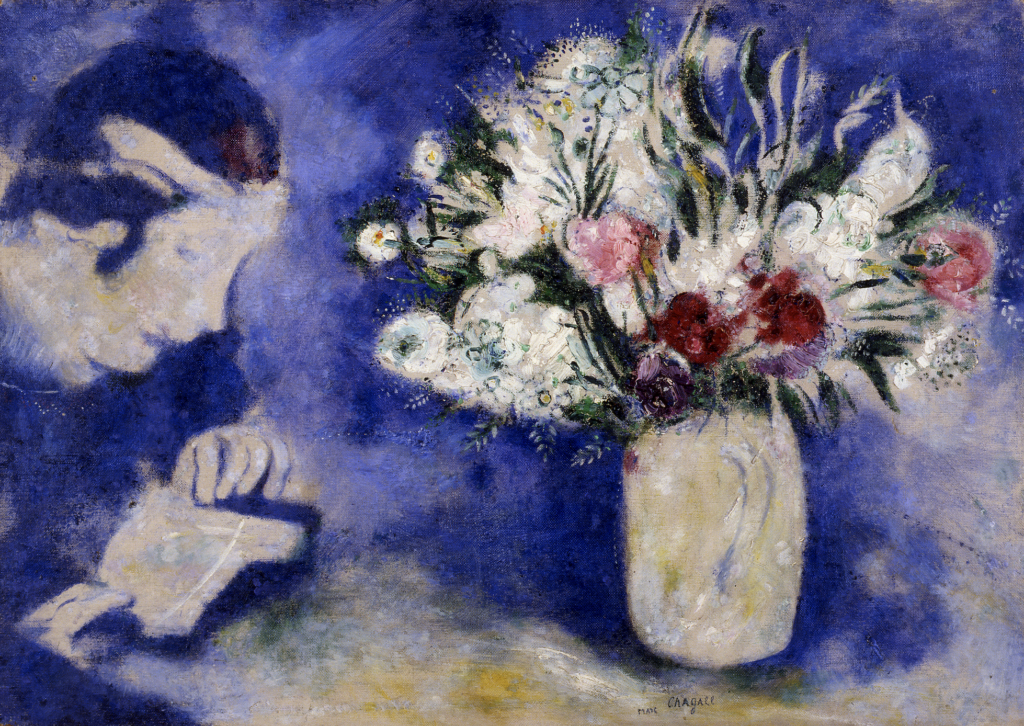

She was the first to sell a picture by Henri Matisse and gave Amedeo Modigliani his one and only solo exhibition. The French painter Raoul Dufy and the Dutch Expressionist Kees Van Dongen were similarly feted. Although taken to task by the French press for her daring to exhibit young artists, Weill kept on keeping on with a veritable all-star team of avant-gardists, including André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Francis Picabia, Georges Braque, Fernand Leger, Diego Rivera, and Marc Chagall. Back in the day, remember, these figures were ridiculed when they weren’t vilified. Weill took them seriously.

Lesser lights just as deserving of attention are featured at the Grey Art Museum, including Kars, Louis Cattaix, Charles Léandre, Simon Lévy, Jean Metzinger, and Jules Pascin, whose work has never looked as good as it does here. Weill also championed women artists like the model-turned-painter Suzanne Valadon and the Fauve-adjacent Émilie Charmy. The dealer would become an inveterate champion and a close friend of the latter. As if we needed additional proof that Weill was a tough cookie, Charmy paid homage to the dealer in the take-no-guff “Portrait de Berthe Weill” (1910-14).

It’s a good picture, but nowhere near as arresting as Charmy’s fierce and sexy “Autoportrait” (1906-07). The curators of “Make Way for Berthe Weill” are likely exhausted after having polished off this venture, and deserve the huzzahs they will enjoy over the coming months. But when they pick themselves up, energy remustered, may I suggest that Charmy be paid a similar tribute? Her work is new to a lot of us and, given its vitality, seems to merit a thorough accounting. The School of Paris is always a good draw. Charmy may prove that it is deeper than we know.