Living by the Sword: MoMA Dips Its Toe Into a Master of Chanbara

Director Kenji Misumi dedicated himself to ‘sword fighting’ pictures. Offers to direct more elevated fare fell on deaf ears. Like American oater auteurs Delmer Daves and Bud Boetticher, Misumi was to the genre born.

Do you want to talk movie franchises? Let’s talk movie franchises. Any and all that come rolling off the tongue — James Bond, “Star Wars,” “Star Trek,” and Rocky — are easily matched, and maybe trumped, by Zatoichi. This mainstay of Japanese entertainment, a blind masseuse who’s an ace hand with a swift sword, has been the subject of at least 26 films as well as a television series that ran 100 episodes. Harry Potter, “Fast and Furious,” and the Marvel Comics crew are pikers in comparison.

Although this series of films, from “The Tale of Zatoichi” (1962) through “Zatoichi: Darkness Is His Ally” (1989), was helmed by a variety of directors, two men vie for the top spot at six pictures apiece: Kimiyoshi Yasuda and Kenji Misumi. While Yasuda has his admirers, Misumi’s got the cred, in large part because of his dedication to chanbara, or “sword fighting” pictures. Offers to direct more elevated fare fell on deaf ears. Like American oater auteurs Delmer Daves and Bud Boetticher, Misumi was to the genre born.

Of course, it takes more than dedication to pull off a good movie. As someone who can’t claim to have dived deeply into Misumi’s oeuvre, I have dipped a toe into its waters and have come away suitably impressed. Not all auteurs are equal, but some are more equal than others — particularly when wielding a sharp implement. The Museum of Modern Art is helping to spread the word with “Kenji Misumi’s Sword Trilogy,” a set of films that will run March 27-April 2.

Kenji Misumi was born at Kyoto in 1921. His father was a Kobe businessman; his mother was a geisha who plied her trade in the pleasure district. Although dad contributed financial support to raising the boy, he didn’t want any direct part in child-rearing; neither did mom. Misumi was raised by an aunt, worked in her restaurant, and attended business school. His real love, though, was chanbara. Telling the elder Misumi as much resulted in his allowance being cut. As luck would have it, a random contact made at Auntie’s diner led to a job at Nikkatsu Studios.

Military service intervened. Misumi was captured by Russian soldiers and spent close to three years in a Siberian prison camp. Upon returning to Japan in 1948, he picked up the ball at Nikkatsu. Misumi worked as an assistant to Kōzaburō Yoshimura, paid attention on the set, and was soon assigned his own projects. His first film, ”Tange Sazen: The Moss Monkey’s Jar” (1954), was a smash. From that point on, Misumi worked steadily up until his death from liver failure in 1975. He was 54.

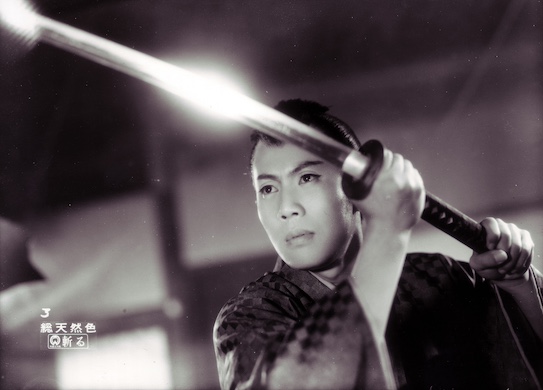

The odd film out in the current MoMA series is “Ken (The Sword)” (1964), being a rarity in Misumi’s oeuvre: the only picture that takes place in a contemporary setting. In this case, it’s a university club dedicated to kendo, a modern martial art predicated on 19th-century precedent. Our protagonist is Jiro Kokubu (Raizō Ichikawa), an unbeatable force on the team and a man whose abiding stoicism is both the envy and the bane of his peers. Not even the come-hithers of a statuesque Eri Itami (Yukiko Fuji) are capable of rattling Jiro. Well, maybe they do rattle him a bit.

“Ken” flits between being a schoolroom drama, a coming of age story, and a sports movie. While there are moments of levity peppering the story, the overall mood is tense and weighted; ultimately, tragedy strikes. Misumi used close-ups as intensively as Sergio Leone, but was also adept at group scenes, handling their back-and-forth with almost balletic aplomb. He’s witty as well: Take note of how a standing fan acts as a fig leaf for Jiro when Eri is most brazen in her seductions.

At a swift 71-minutes, “Kiru (The Sword Cut)” (1962) can’t qualify as an epic, but its elemental structure nonetheless encapsulates several decades, complicated territorial hostilities, family betrayal, and hail-fellow-not-so-well villainies. Ichikawa is on hand again as Shingo, but “Kiru” is, in the end, overshadowed by the ladies.

The movie opens in a jolting fashion as a female assassin (Shiho Fujimura) chases and then kills her mistress under the opening credits. Not long thereafter, a nameless young woman (a feisty Masay Banri) holds off a cadre of warriors by means of a take-it-or-leave-it striptease. Misumi blocks the scene in a manner that is as droll as it is obvious.

“Kenki (Sword Devil)” (1965) is the best of the bunch, what with its mystical portent, stunning deployment of Japan’s natural landscape and the color cinematography of Chikashi Makiura, who drapes the proceedings in warm and fulsome tonalities. The organizer of the exhibition, curator Joshua Siegel, ropes in Gary Cooper and Clint Eastwood as reference points and the analogy holds, martial arts movies being the Eastern equivalent of our Westerns.

Ichikawa, this time round, is Hanpei, a tight-lipped, lower-class loner mocked by his peers. After endearing himself to the reigning shogunate as a gardener with the greenest of thumbs, Hanpei takes up the sword and becomes a mercenary. As ever, Misumi keeps an economical hand on the plot’s machinations: Not a scintilla of celluloid gets wasted.

Michiko Sugata is on hand as the love interest, and though this is very much a guy’s movie, it’s her voice that brings “Kenki” to a close. As for the MoMA program, it’s bound to prompt interest for movie fans who relish genre films for how closely they hew to their limitations and how deftly they expand their possibilities. In that regard, “Sword Trilogy” can’t help but beg for a fuller presentation of Misumi’s oeuvre.