Jazz Records Produced for the Armed Forces in World War II Provide a Unique Snapshot of a Nearly Lost Time

This was a period when almost all of the key styles of jazz were flourishing and vibrantly interacting with each other, and when musicians were prohibited from making records by their union.

‘Classic V-Disc Small Group Jazz Sessions’

Mosaic Records

Listening to an amazing new package from Mosaic Records, “Classic V-Disc Small Group Jazz Sessions,” brings to mind a familiar image from science fiction movies: Picture, if you will, a land beyond time, or, rather, a nebulous place where all time exists at the same time, where you’ll see an ancient Roman chariot parked next to a double-decker bus, a pyramid situated next to a 20th century skyscraper, and more of the same.

The 260 tracks captured in these 11 CDs come from the years 1943 to 1948, which are sort of a moment beyond time in the history of jazz, the absolute midpoint, stylistically if not chronologically. This was a moment when almost all of the key styles of jazz were flourishing at the same instant and vibrantly interacting with each other.

Swing was surely king, as they used to say, but it was also the moment when the world first rediscovered the great pioneers of early New Orleans jazz, many of whom were still playing at peak levels. At the same time, the music soon to be known as modern jazz was emerging — not slowly or subtly but dramatically, with great tumult.

Yet, if you were only listening to commercially issued recordings at the time, you were almost certainly not aware of all this musical activity. For roughly three key years, 1942 to 1944, musicians were prohibited from making records by their union, led by the autocratic Caesar Petrillo, who effectively kept all card-carrying members out of the studio at this crucial moment.

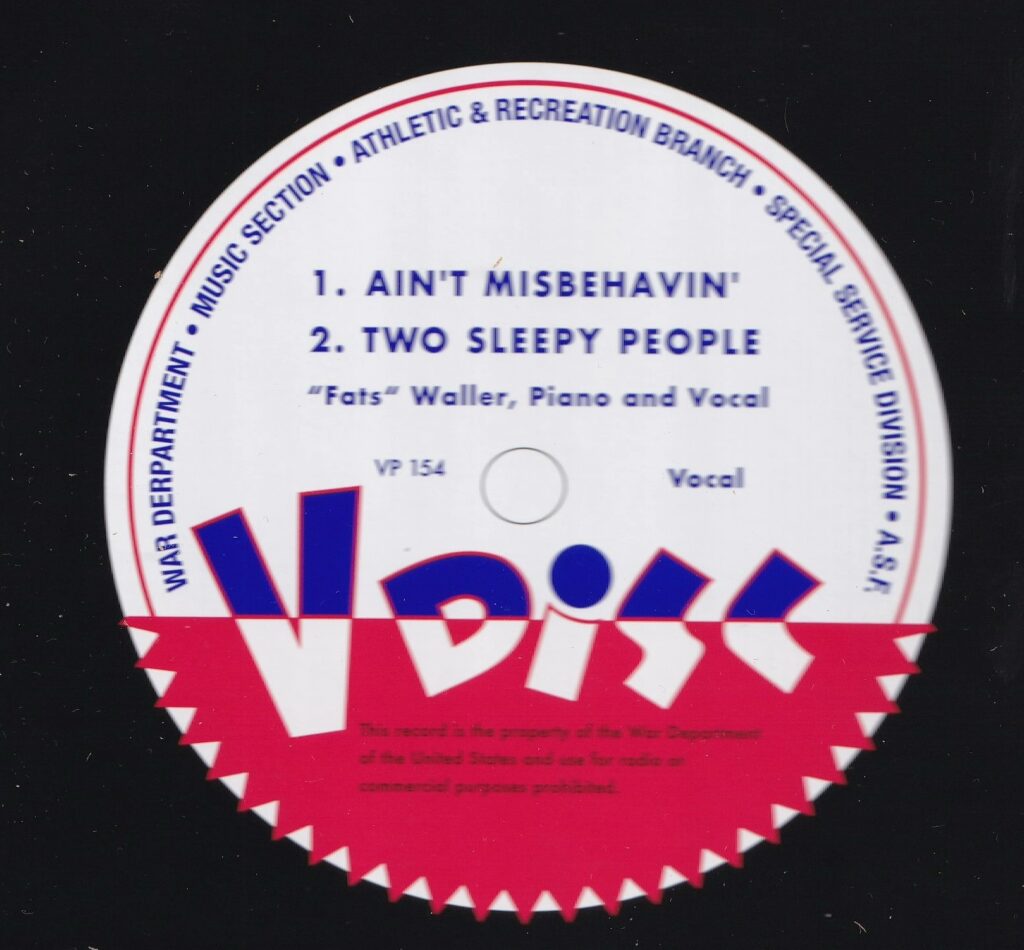

Fortunately, at the same time, a small coterie of jazz-loving producers and critics, including one of my own mentors, “Metronome” magazine’s George T. Simon, got together with the stated aim of creating special recordings of all kinds of music — jazz and everything else — for the express purpose of making records that would be distributed only to servicemen.

The recordings they created are notable, and not just because they were virtually the only sessions produced in those peak years of World War II. For one thing, they were masterminded by true jazz cognoscenti with the aim of producing the best music possible, rather than the usual music business goal of creating hits and capturing market share.

For another, these V-Discs, as they were called, were pressed as 12-inch 78s, meaning that many of the performances were substantially longer than conventional 10-inch 78s, a unique luxury for jazzmen at the time.

The drawback of the longer playing time was that the original V-Discs, distributed amongst the Armed Forces, were often of very low fidelity and had a compressed, “crunchy” sound. Perhaps the single most surprising aspect of this new set, produced by Scott Wenzel, is that the audio is awesome. Engineers Nancy Conforti and Shane Carroll achieved this by drawing from a wide range of sources, including original master acetates as well as exceptionally clean copies of the released discs.

As a result, the performances sound at least as good as standard commercial discs of the late-78 era, and they reflect all the subgenres of jazz that were prevalent in this time. Just for the trumpet players alone, “Classic V-Disc Small Group Jazz Sessions” is exceptional: We start with the Crescent City pioneer Bunk Johnson and progress to the mighty Louis Armstrong, for whom Johnson essentially tried to take credit.

Along the way there’s the dazzling Roy Eldridge, the lyrical Bobby Hackett, the powerful Billy Butterfield, the dynamic Charlie Shavers, the idiosyncratic Muggsy Spanier and Wild Bill Davison, and, near the end, the exceptional Clark Terry, who, like Dizzy Gillespie, managed to be both a modernist and a populist. He’s found here on his first-ever date as a leader, in 1947, playing a relaxed version of the classic Charlie Parker blues “Billie’s Bounce.”

What goes for trumpeters is possibly even more so for pianists, and the package is worth the price for the rare tracks by Fats Waller and Art Tatum, not to mention Lennie Tristano. There’s also a subsection of “chamber jazz” groups that were obviously modeled on the very popular King Cole Trio, starting with some scarce and excellent tracks by Nat King Cole’s own classic threesome with guitarist Oscar Moore and bassist Johnny Miller.

There’s the Loumell Morgan Trio, which was more concerned with vocal harmony and abundant jive; the Page Cavanaugh Trio, with virtuoso guitarist Al Viola; the Erskine Butterfield Trio; the Vivian Garry Trio; and some remarkably Cole-ish piano from the 17-year-old André Previn, working with Cole’s own sometime sidemen bassist, Red Callender, and guitarist Irving Ashby.

The delights of this set are far too numerous to delineate here, and thankfully the “Jazz Lives” blogger, Michael Steinman, has supplied us with a comprehensive annotation. I’m particularly taken with a tantalizingly brief set of trumpet-piano duets involving Bobby Hackett and Joe Bushkin. There’s also a stylish session directed by arranger-composer-bassist Bob Haggart featuring a variation on “What Is this Thing Called Love” that anticipates Tadd Dameron’s “Hot House,” and some amazingly precise trio interplay between drummer Gene Krupa and saxophonist Charlie Ventura.

Even aficionados will be surprised by the abundance of great jazz singers here, including the legendary Mildred Bailey near the end of her career and the emerging Jo Stafford, at the start of her own. We are also treated to some of Connee Boswell’s finest solo work, as well as excellent tracks by big-band vocalists in different settings, like Helen Ward, Martha Tilton, and Betty Roché.

While there are some lesser-known players here, such as the excellent Brazilian singing pianist Dick Farney, a.k.a., Farnésio Dutra e Silva, the standouts include excellent tracks by two of the biggest names in American music.

Louis Armstrong has a beautiful reading of “I’m Confessin’” and a standout duet with Jack Teagarden titled “Jack-Armstrong Blues” (1944), and there are two terrific four-minute standards by Ella Fitzgerald with an all-star ensemble, “I’ll See You In My Dreams” and “I’ll Always Be In Love With You.” They are substantially better than anything she was recording for Decca in these years.

Yet if there’s one track that captures both the solemnity and the irreverence of the war years and the V-Disc program, it’s “Uncle Sam Blues” by Hot Lips Page, which begins with an unforgettable reference to the national draft: “Uncle Sam ain’t no woman / But he sure can take your man.”

During my program on KSDS this week I am presenting a three-hour program of some of my favorite tracks from this new package. You can listen to it here.