James Seward, a Promising Young Painter, Reconstructs, With Eerie Hyperreality, Iconic Cinematic Embraces

The sincerity of each painting shows us that there is a generous portion of the artist that truly wants to believe, to hold on to these moments as genuine.

James Seward: ‘Embrace: Cinematic Moments’

Hudson River Museum, 511 Warburton Avenue, Yonkers, New York

February 2, 2024 – May 12, 2024

A very promising young painter whose show opens at the Hudson River Museum today, James Seward, is a bright outlier in the new art year. “Embrace” is the titular pretext for the show by Mr. Seward, who has in the past tackled iconic emotional moments from pop culture, such as smiles or tears. Mr. Seward is intent on portraying universal human gestures as they are played out on the stage of celebrity culture, press, or film, and the results are always engaging.

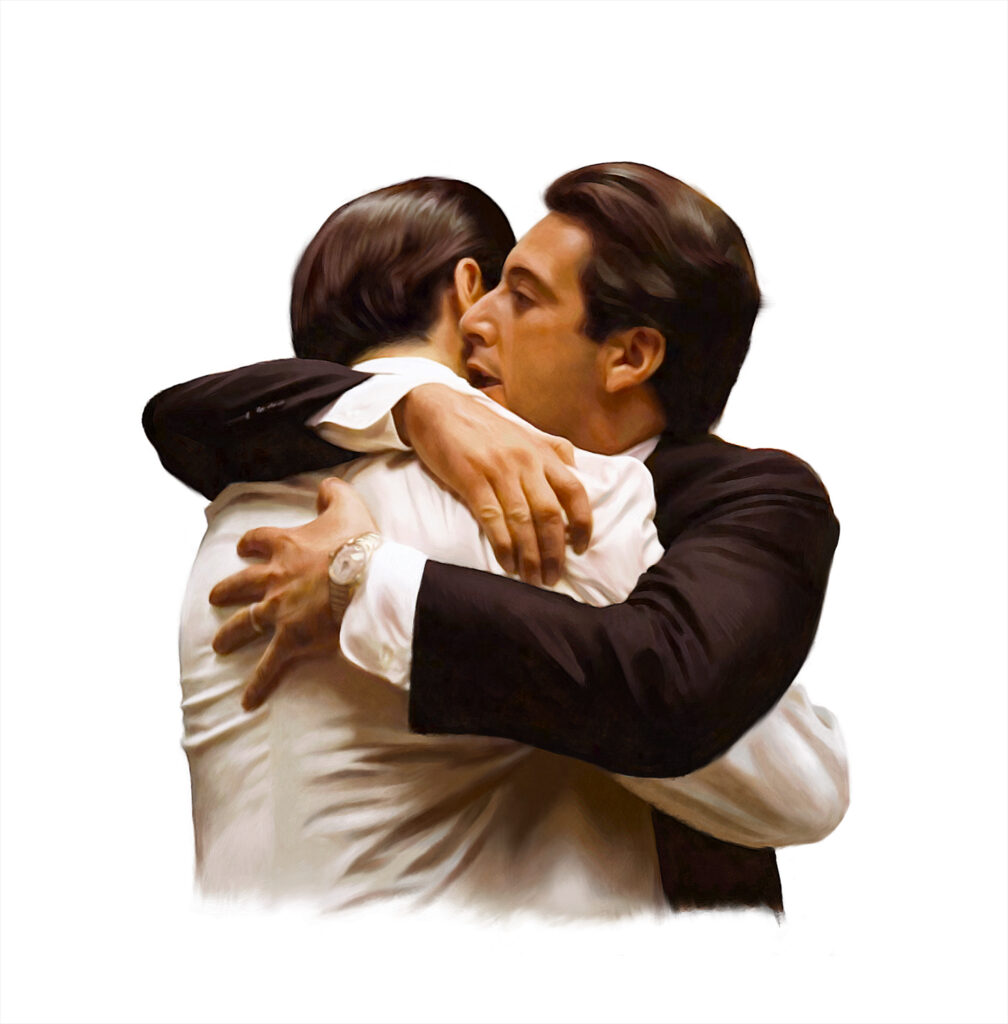

In this show, Mr. Seward tackles cinematic embraces. There are famous hugs from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “The Godfather Part II,” “Brokeback Mountain,” “12 Years a Slave,” “It’s a Wonderful Life,” “The Wizard of Oz,” and “The Farewell.” With a realism and polish that beggar belief, Mr. Seward reconstructs each embrace in exhaustive detail. Every costume fold and crease, every gestural nuance, every facial expression is present. For the films in Black and White, the same are reproduced in greyscale.

The results are paintings with an eerie hyperreality that nonetheless speak to the fun house that is contemporary culture. Mr. Seward officially states that each work directly portrays poignant moments of connection from films he loves and that each moment has a direct connection to his personal history. As such, they are a paean to the deep impact that portrayals of human connection have had on our lives, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Some do appear to be sincerely straightforward. There is the hug between “Chief” Bromden and McMurphy from “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest,” titled “You’re Coming With Me,” or the gathering around Solomon’s grandson from the closing scene of “12 Years a Slave,” titled “‘Please Forgive Me’ ‘There’s Nothing to Forgive.’” These are moments of deep emotion and closure, and we relive them as such.

However, other embraces Mr. Seward paints are not necessarily the ones we believe them to be. A subtle bait and switch is taking place, and it seems intentional.

Take the “bacio della morte” from “The Godfather II,” titled, “You Broke My Heart.” As one of the most iconic and chilling embraces in cinematic history, we are inclined to think that Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone has just finished giving the kiss of death to John Cazale’s Fredo Corleone. However, the embrace is from just before, when Michael tells his brother, “There’s a plane waiting for you.”

We are also told that Awkwafina embracing her grandmother from “The Farewell,” “Don’t Cry,” is the iconic hug where her dying matriarch says her goodbyes. Yet it more closely resembles Awkwafina’s tentative, and deeply ambivalent, first hug when her grandmother first receives her. Which one is it?

The same for the embrace from “Brokeback Mountain,” “What are you Doing Here?” which is not from any penultimate romantic moment, but from the moment where Jack realizes Ennis will never leave his wife for him. However accurate Mr. Seward’s portrayal of an exact filmic moment, we are primed to second guess ourselves and go down an ever-receding rabbit hole of recollection, re-enactment, and doubt upon viewing them.

With all this ambiguity astir in our press saturated noggins, the pretext for Mr. Seward’s slick realism becomes more evident. His subject is not reality but hyperreality, the purely fantastical realm of meticulously constructed images that mirror “real” life, the ways we respond to them, and the ways we second guess ourselves. He also highlights those moments where purely constructed narrative moments become emotional touchstones, the point where fiction becomes “real.”

Mr. Seward, who spent ten years as an assistant in the studio of Jeff Koons, learned from Mr. Koons’s hyper-perfectionist methods of painting, which include a computer-assisted method of color grading that sets the colors of an image before the brush even hits the canvas. When Mr. Seward struck out on his own, he brought Mr. Koons’s studio methods with him, and one imagines a touch of his cold, hyper-intellectual playfulness as well.

It’s not all refined technique and cynical expose, however. The sincerity of each painting shows us that there is a generous portion of Mr. Seward that truly wants to believe, to hold on to these moments as genuine. The fact that they are themselves painstakingly constructed and misleading is beside the point. In reproducing them, he shows us he also wants to surrender to them, to amplify their alleged universal resonance and significance.

Somewhere amid all the hyperbole, however, the dream becomes a maze, and sincerity gets supplanted by unease, if not melancholy. We want to believe and love the cinematic dream, but it’s hard to see straight. This internal struggle is central to what Mr. Seward is painting. It’s probably what makes him one of our first post-contemporary painters.