Irish Repertory Theatre, With ‘Beckett Briefs,’ Stages Three Short Works by the Master Playwright

The Beckett classic ‘Krapp’s Last Tape,’ which includes a master class in acting from F. Murray Abraham, is featured along with ‘Not I’ and ‘Play.’ Irish Rep’s producing director, Ciarán O’Reilly, expertly helms the collection.

For a master class in acting that takes less than a minute of your time, check out F. Murray Abraham peeling a banana in Irish Repertory Theatre’s new staging of “Krapp’s Last Tape.” That Samuel Beckett classic is the last and most famous of three short plays the company is presenting as “Beckett Briefs,” and it’s well worth the price of admission on its own.

That’s not to dismiss the entertainment value of the other two, even shorter pieces featured in “Briefs.” Expertly helmed by Irish Rep’s producing director, Ciarán O’Reilly, this collection poses the burning existential questions that inform Beckett’s work with a grace and buoyancy that serve both its playful absurdism and its fundamental, exquisite bleakness.

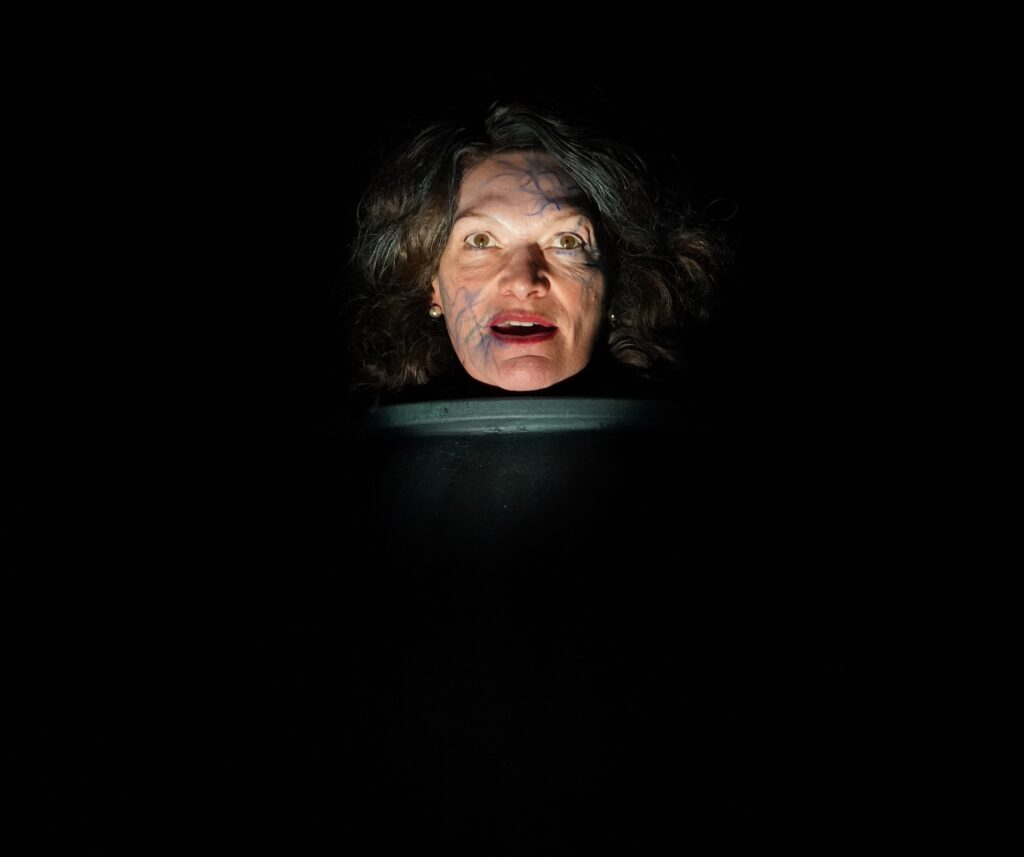

Charlie Corcoran’s scenic design and Michael Gottlieb’s lighting set a foreboding tone; the show opens with a woman’s mouth materializing out of total darkness, several feet above the stage. Those in the know will immediately recognize the play as “Not I,” and its sole character as an old woman who, after having been mute for more than 70 years, has suddenly found her voice.

The actress Sarah Street conveys the comical and plaintive aspects of this woman’s plight, born of early abandonment and trauma; there are more than a dozen references to the “buzzing” in her head, and she also points to “something begging in the brain” and “something she had to … tell.” Ms. Street’s bright, sometimes shrill tone lends the necessary urgency to her frantic rush of observations and queries.

There are three characters in the second selection, “Play,” and we see their entire heads whenever they’re speaking, while their bodies are obscured behind a set of funereal urns. Like Sartre’s “No Exit,” “Play” introduces us to three souls, a man and two women, trapped together in the afterlife; in this case, they were intimately acquainted on Earth, where one woman was the man’s wife and the other his mistress.

There is again an air of desperation, at once funny and creepy, along with a pronounced sense of futility: Each head is illuminated only when the character speaks, or when they speak in unison, at which point their appeals become mostly unintelligible. Ms. Street plays the mistress, identified in the script as “W2”; here her voice takes on an effectively jarring perkiness, sliding neatly into the character’s periodic, strident peals of laughter.

Kate Forbes’s W1, in contrast, is stern and matronly, and ripe with indignance, while as M — the unfaithful husband — Roger Dominic Casey adopts the accent and manner of a louche, working-class Brit. His lines are punctuated, tellingly, with hiccups; plainly, this chap was ill-suited to manage any pair of women, let alone these two.

Krapp has long forsaken such relationships. We meet the 69-year-old man in his cluttered den, which like the scatologically named character himself stinks of disrepair. Costumed by Orla Long in tattered clothes, Mr. Abraham spends his first minutes onstage in silence, broken only by grunts and groans — some mildly approving, as when he appraises that banana, with a look of bemused wonder suggesting the discovery of a lost gem — that pose a marked contrast to the rapid-fire verbal cascades in the other plays.

That contrast continues once Krapp starts speaking — and listening, to recordings he made decades ago, when the rot of cynical resignation that has since consumed him was beginning to set in. Just as, at 39, he dismissed the “young whelp” he once was, the elderly Krapp sneers at his musings in early middle age, with their lingering wisps of romance and ambition, their mooning over women’s eyes.

Mr. Abraham’s vigorous but measured delivery — the play allows him a much wider range in terms of tempo and dynamics than the other pieces — also emphasizes, piercingly, how much of Krapp’s humanity remains intact, in spite of himself. Some of the most moving moments are non-verbal, such as when he bows his head and cradles the tape machine while his younger voice recalls, with unabashed lyricism, a tender encounter with a woman — a far cry, clearly, from the occasional visits from a “bony old ghost of a whore” that now constitute his love life.

It’s an enduringly hypnotic and haunting portrait of a life squandered, painted without judgment or counsel. And like the other plays in “Briefs,” it’s presented here with a mix of gentle reverence and panache that puts those virtues front and center.