Iranian Tyranny and Examples of Resistance Inspire Amir Reza Koohestani’s ‘Blind Runner,’ Now Being Staged in North America for the First Time

For Koohestani, running is more than a metaphor. The athletic pursuit became therapeutic following the Iranian government’s violent crackdown on demonstrators in the country’s Green Movement.

“There are two kinds of runners: those who run to clear their heads and those who run to think.” So posits a character in “Blind Runner,” a one-act drama by an Iranian writer and director, Amir Reza Koohestani. In the play’s North American premiere, now being staged at Brooklyn’s Saint Ann’s Warehouse, the line, like all the others, is spoken in Farsi, with English supertitles provided for those who don’t understand the Persian language.

For Mr. Koohestani, running is more than a metaphor, though he uses the sport lavishly in that capacity throughout the play. The athletic pursuit became therapeutic following the Iranian government’s violent crackdown on demonstrators in the country’s Green Movement, which protested the re-election of President Ahmadinejad in 2009. As the playwright explains in a program note, “Running was an alternative to the demonstrations that were no longer being held and the freedom that had left us again for the umpteenth time.”

For “Runner,” Mr. Koohestani also drew inspiration from specific examples of tyranny and resistance — notable among them the death in 2022 of Mahsa Amini, after that young woman was arrested by so-called morality police for defying the Islamic government’s rigid dress code, and the subsequent imprisonment of female journalist Niloofar Hamedi, whose report on the incident helped spur the “Woman, Life, Freedom” slogan and movement.

Ms. Hamedi, who had also covered sports and incorporated running into her life behind bars, and her husband, a marathon runner who has made use of that pursuit in a campaign for his wife’s release, were apparently role models for the play’s two central figures: an imprisoned female political activist and her spouse, neither of them named, respectively played by Iranian actors Ainaz Azarhoush and Mohammed Reza Hosseinzadeh.

The third character, also played by Ms. Azarhoush, is identified as Parissa; she is the literal blind runner, having been shot in the eyes while taking part in a demonstration. Formerly a marathoner herself, Parissa is now training at Paris; the prisoner’s husband, we learn, will serve as her guide on a mission — involving crossing the Channel Tunnel — that’s quite possibly even more perilous than whatever activism landed his wife in jail.

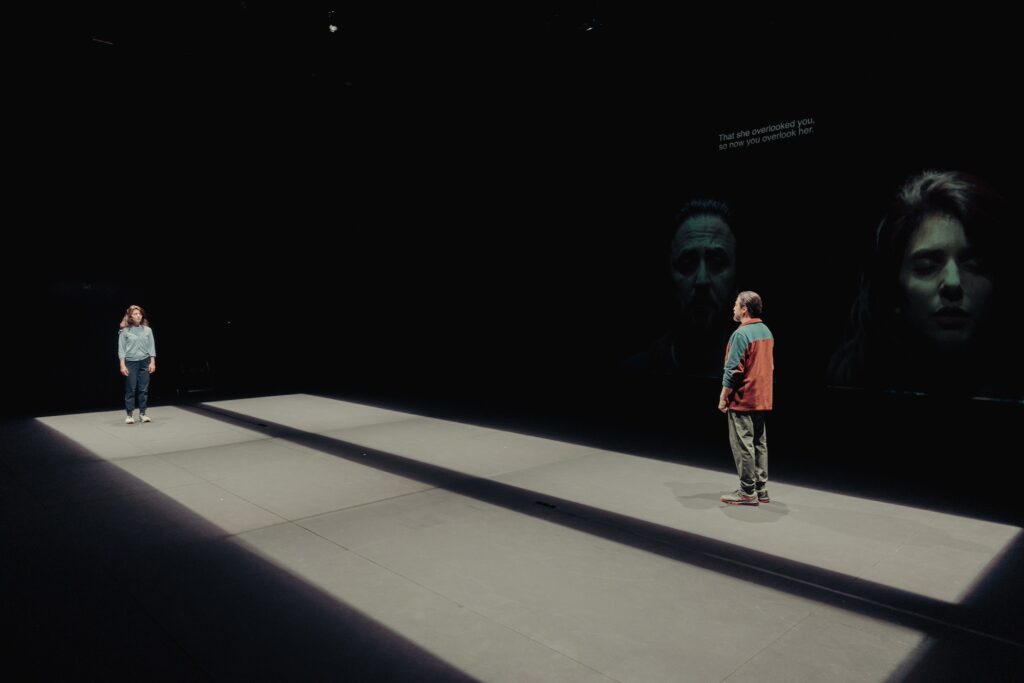

Parissa’s sex is a key factor here. The prisoner has encouraged her husband to join this other woman in a collaboration that’s inherently, profoundly intimate. This is emphasized by having the performers jog across the stage in various directions that are either reflected or contradicted by Yasi Moradi and Benjamin Krieg’s alluring video design.

Both Mr. Koohestani and the Iranian-born company staging this production, the Mehr Theatre Group, are known for bringing a cinematic sensibility to their work, and repeated closeups of the delicately beautiful Ms. Azarhoush and the more scruffily endearing Mr. Hosseinzadeh underline the nuances in the acting and the dialogue.

“We breathe in and breathe out together,” the husband says at one point; he’s describing his interaction with Parissa, but he and his wife do much the same in sequences that are made even more sensual — almost erotic at points — by music provided by Philip Hohenwarter and Matthias Peyker.

There are other moments that hardly pulse with carnal or emotional intensity. Standing together against Éric Soyer’s stark set and either facing each other or, more often, the audience, Mr. Hosseinzadeh and particularly Ms. Azarhoush can deliver their lines in a low key that would likely register better on screen than it does here.

This sense of subtlety can be more effective when Mr. Koohestani is addressing the wife’s plight. “I’m not here with you,” her husband says at one point. “I don’t know what’s going on.” She could be speaking not just for political prisoners but for all the women who have led restricted, oppressed lives since Iran’s revolution more than 45 years ago when she responds with: “Can’t you imagine?”

Mr. Koohestani does not, in fact, address this issue in great detail; “Blind Runner” is at its most pointed when the subject shifts to migration, and Parissa, who appears to have drawn international attention, observes that she has received better treatment than so many others seeking refuge. “I don’t want to steal this recognition from them,” she insists.

Granted, there is plenty of intersection between migrants and women who have suffered similarly to the female characters in “Blind Runner,” and in countless other ways. Throughout the production’s run, St. Ann’s will present a series of programs titled “Unseen Iran: A Celebration of Iranian Art & Culture,” which will no doubt reflect — like the play does — how they have also managed to persevere.