Hold That Tile: The Art, Life, and Loves of Carol Janeway Are Finally Reprised in a Biography and Catalog Like Few Others

It’s the full scoop on a ceramicist who startled Manhattan culture in the 1940s and pioneered the modern art of decorative ceramic tiles, jewelry, furniture — and custom doorknobs for Marilyn Monroe.

‘The Art of Carol Janeway’

By Victoria Jenssen

Friesen Press, 468 pages.

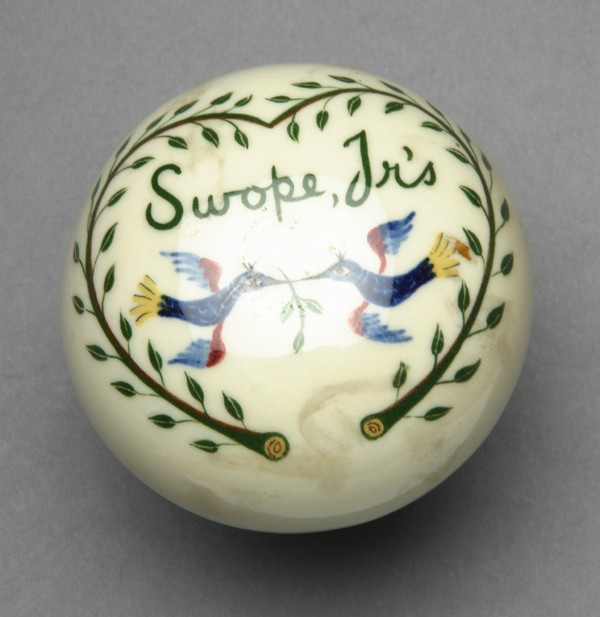

Carol Janeway was a ceramicist and artist who had a successful career in Manhattan. At its height, in 1940s and 1950s, she produced hand painted ceramic tile, ceramic jewelry, buttons, decorative ceramic fixtures and furniture, painted wheel thrown ceramics — including a commission of plates for Wedgewood — and celebrated chess and checker sets. She produced gouache paintings. All were much sought-after in their time.

Now — finally — the artist and her art are the subject of an important book, reprising her vast oeuvre and remarkable life, to which her biographer, Victoria Jenssen, devoted years of work. It’s an unorthodox, weighty, but highly readable tome — a combination of catalog, biography, and personal tribute, with hundreds of illustrations of Janeway’s work and photographs of the artist herself.

Self-taught, Janeway created signature animal motifs with a deft simplicity and folksy charm. They blended well with her era’s modernist aesthetics. Her tiles still grace the fireplace surrounds, kitchens, and doors of many a New York brownstone. Her ceramics and tiles were also a feature of one of the luxury gift shops, Georg Jensen Inc., between 1942 and 1950.

So in vogue were Janeway’s decorative items that Marilyn Monroe acquired five of her doorknobs to decorate a three-bedroom Mexican-style house. Yet Janeway has also been a bit of a mystery, which sparked Ms. Jenssen’s 15-year biographical odyssey. Intrigued after finding a pile of Janeway tiles owned by her parents, Ms. Jenssen began to piece together Janeway’s life and oeuvre.

Ms. Jenssen began by looking up relatives, friends, collaborators and correspondents. She traced Janeway’s beginning as a ceramist, during which period she had to borrow kiln space. Ms. Jenssen followed the story to Janeway’s years as a artisan running her own Manhattan production studio. What emerges is a reconstruction of the milieu a unique figure in 20th century art and artisanal ceramic craft. It is also an exhaustive catalog of her output.

The biography also portrays a fascinating period in Lower Manhattan. Janeway was a figure in the post-war politics and bohemian culture of the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village. She was a friend and colleague of prominent painters, printmakers, poets, writers, scholars, film makers, and activists. She would eventually fight alongside Jane Jacobs for the preservation of Milligan and Patchin Places.

Janeway was the wartime muse and lover of the Russian-French sculptor Ossip Zadkine, who sculpted the ceramist’s portrait, now in bronze, and Janeway was photographed by surrealist filmmaker Maya Deren. Ms. Jenssen paints Janeway as a Brooklyn-born, educated beauty who enjoyed social attention, and relished in self-mythologizing.

The artist spoke with a New York society drawl. Equally at home in the Bohemian Village as she was with society ladies of the Upper East Side, Janeway was a self-promoter. Her relationship with Georg Jensen, Inc., began when she marched into the store unannounced and pulled two of her decorative ceramic tiles out of her purse. This sparked a relationship with the import retailer that lasted over a decade.

Janeway’s face graced newspapers and magazines. Commissions for her wares soared. By the 1950s, she would produce a how-to ceramics book, “Ceramics and Potterymaking for Everyone.”

Along with her talent for self-promotion, Janeway had a knack for stormy liaisons with older mentors. Her relationship with Zadkine ended abruptly and is described here for the first time. Her daughter, Kiske, born in Soviet Moscow in 1935, was her only offspring. She was interviewed extensively for the book.

Ms. Jenssen’s exploration of these details gives a more complete portrait of the woman, not just the artist. Janeway sprayed clear lead glaze on her ceramics and by 1950, had retired, diagnosed with lead-poisoning. Jenssen suggests her quirky behaviors may be attributed to the lead. She lived another 39 active years before succumbing to mouth cancer and pneumonia.

Ms. Jenssen’s unconventional approach is less straight-ahead biography and more of a painstaking forensic reconstruction, during which she went through receipts, correspondence, diary entries, catalog orders, and archives, then painstakingly cross-referenced the information.

The result is a delightfully detailed biography-cum-catalog, bursting with salient and entertaining tidbits about Janeway’s life interspersed with archival photographs of her expansive output. Janeway’s ceramics were always striking, and her career was intriguing. This labor of love restores a neglected artisan to her rightful place in the annals of American 20th-century craft.