Happily, for a Book on a Weighty Subject, ‘The Avant-Gardists’ Has an Author With a Sense of Humor

Sjeng Scheijen keeps up a convivial tone throughout the book. Given the time-frame and circumstances under discussion, this isn’t easy: ‘The Avant-Gardists’ is, in significant part, a story of almost unutterable naivete.

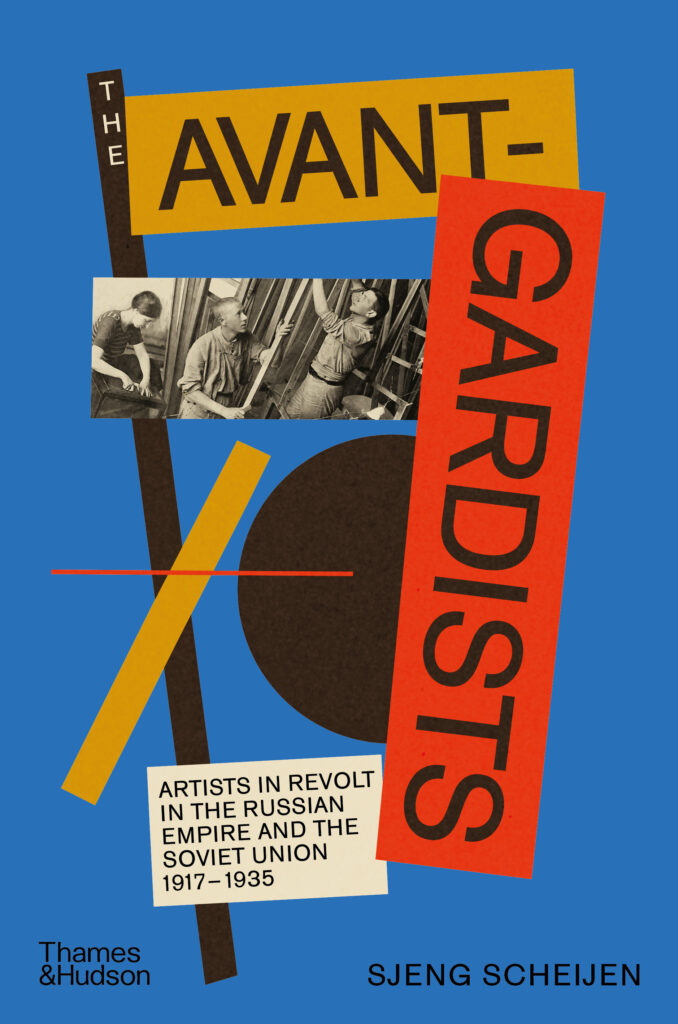

‘The Avant-Gardists; Artists in Revolt in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union 1917-1935’

By Sjeng Scheijen

Thames & Hudson, 504 Pages

Art historians aren’t, by general reputation, a funny lot, nor does the average art historical tract brim with wit. Yet within two pages of a new book, “The Avant-Gardists; Artists in Revolt in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union 1917-1935,” it is clear that the author, Sjeng Scheijen, has a sense of humor.

In an introduction titled “Why We Paint Ourselves,” the independent scholar and curator takes us to Moscow on September 14, 1913. Two days prior, the painter Mikhail Larionov had announced in a newspaper interview a challenge to the status quo: He planned to paint his face and walk the length of a major Moscow thoroughfare, Kuznetsky Most. Larionov encouraged men to join him by “weav[ing] ribbons of gold and silk into their hair” and to shave off half of their beards. Not forgetting the ladies, he advised them to join this event with breasts bared.

No partial beards or naked bosoms were seen that day and the public response was, let’s say, meh. Still, in the weeks that followed, Larionov and a coterie of pals continued with this kind of stunt and ultimately did manage to raise hackles. The press pitched in with admonitions. Upstanding members of the bourgeoisie attacked the provocateurs physically and tried to forcibly remove their make-up. A film was made, “Drama in the Futurists Cabaret no. 13,” the screening of which, Mr. Scheijen writes, “showed—to everyone’s relief—some exposed women’s breasts.”

To everyone’s relief — or, at least, to those of us who are taken with the byways of 20th-century art — Mr. Scheijen keeps up this convivial tone throughout the book. Given the time-frame and circumstances under discussion, this isn’t easy: “The Avant-Gardists” is, in significant part, a story of almost unutterable naivete. Headstrong personalities like Larionov and Wassily Kandinsky got caught up in a torrent of political and social upheaval. They thought they were ready for it; they weren’t.

The Russian avant-gardists — or, as they were commonly referred to, the futurists — welcomed the October revolution, but without giving much thought to its theoretical underpinnings or possible ramifications. Mr. Scheijen writes of how “this set of brilliant, talented crackpots, libertines and hard-working gadabouts ended up in the stifling morass of Stalinism.”

Post-tsarist Russia made for a giddy sense of possibility and an unavoidable battle of wills and egos. Two of the main players of “The Avant-Gardists” are pioneering abstractionists Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin. Malevich was prone to grandiosity; Tatlin to paranoia. Each man cultivated his own followers. Both were capable of acting like children. The story of how these paragons of Modernism behaved during the mounting of a 1915 group exhibition titled “0.10” is a farce worthy of the Three Stooges.

Mr. Scheijen takes us through the awkward romance between the “proletarians of the brush” and a revolutionary state, underlining that the only commonality they truly shared was a nihilistic anti-traditionalism. By 1922, the Leninist regime had begun to call into question the tenets espoused by our heroes. A decade later, the state introduced a new policy for art, that it “was to become a form of social mobilization, a means of promoting loyalty to the regime among the people.” Goodbye, modernism; hello, Social Realism.

The writing was on the wall. “I am unable to see the works of expressionism, futurism, cubism and other ‘isms’ as the greatest manifestation of artistic genius … they give me no joy whatsoever”: Lenin’s takedown of modernism was, in fact, printed directly on a wall at a 1932 exhibition, “Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.” Some members of the avant-garde tucked in their tails and accepted an increasing marginalization; others bent over backward to serve the state. And then came Stalin and his purges of “any elitist or cosmopolitan tendencies….”

Toward the end of Mr. Scheijen’s book, there is a reproduction of a charcoal portrait of Tatlin by his then-girlfriend, Alexandra Korsakova. The picture was rendered in 1953, a good three decades after the revolution and the year of Tatlin’s death. The visage is a veritable death’s head, the facial features swathed in darkness and the eyes open wide and clearly haunted. “Without riddles…,” Tatlin told a friend in his last days, “there will be no art.” “The Avant Gardists” is a sobering story told well and told roundly. It is likely the best overview of the era we’ll have for some time.