‘Gods of Mexico’ Is Fine Cinéma, but Don’t Go for the Vérité

Marketed as a documentary, the debut feature by Helmut Dosantos is rife with artifice: Every event seen during the course of the picture has been staged.

“Art,” Pablo Picasso stated famously, “is a lie that makes us realize truth.” All art forms, to one degree or another, trade in fiction — that is to say, the shaping of experience through means that are separate from it. Even mediums that seem to promise verisimilitude, such as photography, have long proved susceptible to manipulation, fabulation, and, sometimes, deceit.

“Gods of Mexico,” the debut feature by Helmut Dosantos, is being marketed by the good folks at Oscilloscope Laboratories as a documentary — which it is, I suppose. Mr. Dosantos and his crew spent a considerable amount of time setting up shop in far-flung corners of the country. Their mission? To chronicle “local cultures that express a unique relationship with their environment.” The purview of the film is, in its emphasis, distinctly anti-globalist.

“Gods of Mexico” is divided into sections with titles that touch upon the poetic (“Windrose Rhapsodies”), the mythical (“Huitzilopochtli,” the Aztec god of sun and war), and the topographical (“North,” “East”). “White” and “Black” bookend the movie, corresponding to the colors of their subjects: the cultivation of salt and the digging of coal.

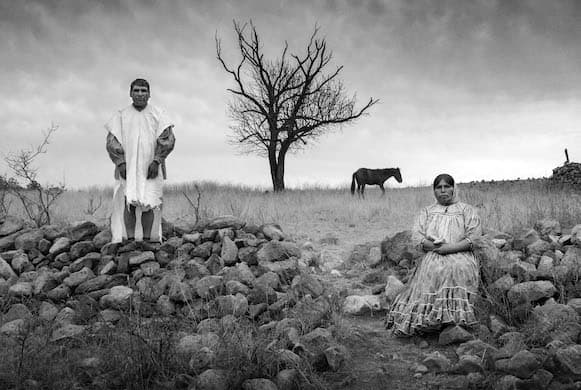

Narration is notably absent; dialogue is overheard and rare. Enrico Ascoli, an artist whose metier is sound, amplifies, distills, and clarifies the ambient noise of a given moment, making it evocative of greater forces at work. Color is used in conjunction with black-and-white shots, and time sometimes slows to a crawl. The mid-section of the film is dedicated to portraits in which the sitters hold a pose and confront the viewer for up to 30 seconds at a time.

“Gods of Mexico” is, in so many words, not a typical travelogue. There’s no attempt to ground the viewer in terms of history, narrative, or character. Linearity and scholarship are jettisoned in the cause of pure sensation. Do you want an immersive experience? Mr. Dosantos obliges: This is a picture that washes over the viewer and, truth to tell, it’s pretty seductive. A variety of cinematographers worked on the film, including the director himself, but the results are uniform in their sumptuousness.

How much of a document “Gods of Mexico” might be — that is to say, how true it is to what we see — is a concerning question. Early on in the film, as we watch men prepare ground for the gleaning of salt, the camera is situated in ways that invite head-scratching. The same is true as we follow a group of miners during the final moments of the film. It becomes clear that the scenes aren’t filmed head-on so much as choreographed. We’re made privy to vantage points that strain at the limits of cinéma vérité.

As it turns out, Mr. Dosantos has a pretty elastic idea of just what it is that constitutes vérité. In an article published in Vox, Zaki Lawrence extols the director’s “breaking [of] documentary norms.” It is there that we learn that “Gods of Mexico” is rife with artifice. Every event seen during the course of the picture has been staged: All of the participants were asked how they would best be represented on camera. Does Mr. Dosantos, pace Picasso, realize truth?

The section of the film dedicated to citizens of Mexico — the farmers, fishers, traditional doctors and iguana hunters — is particularly problematic, not least because we are aware of just how contrived each tableau is. The camera, by virtue of being present, instills self-awareness; holding still for it only presses the point. Is a “portrait of a nation through its land and peoples” well-served by meta-manipulation? Perhaps.

How much pleasure is derived from Mr. Dosantos’s stunning film will depend, in significant part, on the viewer’s willingness to privilege beauty over truth. It’s hard to argue with the merits of doing so when watching the film. Only in retrospect does ‘Gods of Mexico” nag at the conscience.