‘Giants,’ at the Brooklyn Museum, Samples Decades of Black Art Collected by Alicia Keys and Swizz Beatz

The collection is impressive, even if the presentation seems a bit too flat, too crowded, and a tad too hagiographical towards its sponsors.

‘Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys’

Brooklyn Museum of Art, 200 Eastern Pkwy, Brooklyn, NY

February 10, 2024 – July 7, 2024

Giant is the key word for the Brooklyn Museum show “Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys,” which lavishes 98 works by 36 artists across the museum’s main floor, featuring African American, Afrocentric, or African artists across the globe collected by the superstar power couple. The show, spanning historic pieces from the 1950s and works as recent as 2017, gives a broad sampling of Black art.

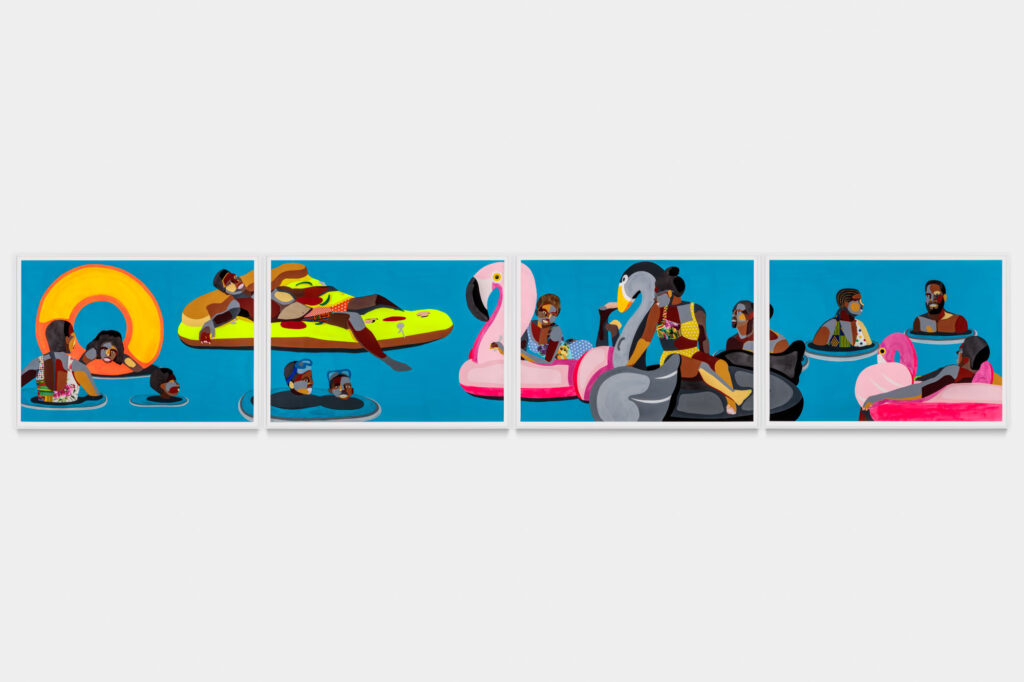

The collection, as to be expected, is geared towards issues of Black representation, especially in contemporary fine art. Take the 2018 painting by Derrick Adams, “Floater 74,” which portrays Black men, women, and children relaxing in a pool. The artist was cognizant of a paucity of images in fine art, and in the culture at large, of Black people at leisure, especially in the water. There were many depictions of labor, struggle and protest, and plenty of representations of sportsmanship, but where were they relaxing?

Mr. Adams’ playful and colorful quasi cubist style — using paint, fabric and collage — engages with stereotypes of black labor, freedom of assembly and leisure, all in a way that has been described as “radical.” There is certainly a tension being created between the brightly cheerful surfaces of his work and its social subtexts.

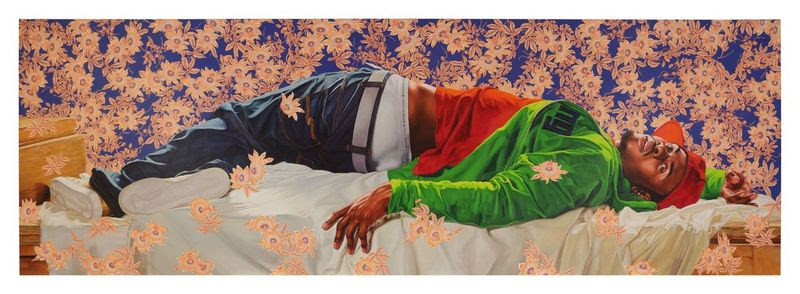

Among the highlights of the show is a massive painting by Kehinde Wiley, who is probably most famous for painting President Obama against a wall of greenery. Here, Mr. Wiley contributes an enormous canvas, “Femme piquée par un serpent.” A whopping 25 feet long, it dominates its chosen room with Mr. Wiley’s usual theme: the replacement of white subjects from historical artworks with ones that are Black.

This painting takes the writhing nude woman from Auguste Clesinger’s 1847 marble sculpture of the same title — a masterpiece of French neoclassical kitsch portraying his patron’s young mistress — and replaces her with a young Black man, wringing out all of its attendant queer and racial ironies. It’s a joke he’s painted before, and it feels a bit thin as the basis for a painting on this monumental scale, not unlike a film billboard. Then again, given the source material, it’s only fitting.

Given the massive extent of the collection, there are some unexpected surprises. Their collection of Barkley L. Hendricks, for instance, who is known mostly for his incredible portraiture, is represented here with a collection of 14 of his seascapes and landscapes, all in oval, circular, or unusually shaped frames. They are painted with Hendricks’s usual unerring and fanatical attention to detail, and their presence here is a declaration.

The lion’s share of the painting is figurative, though there are some interesting exceptions. Nina Chanel Abney’s “catfish” is an ironically blatant commentary on the interrelationship of sex and commerce, done with an almost caricaturist modernism. It’s just angry and blatant enough to crackle.

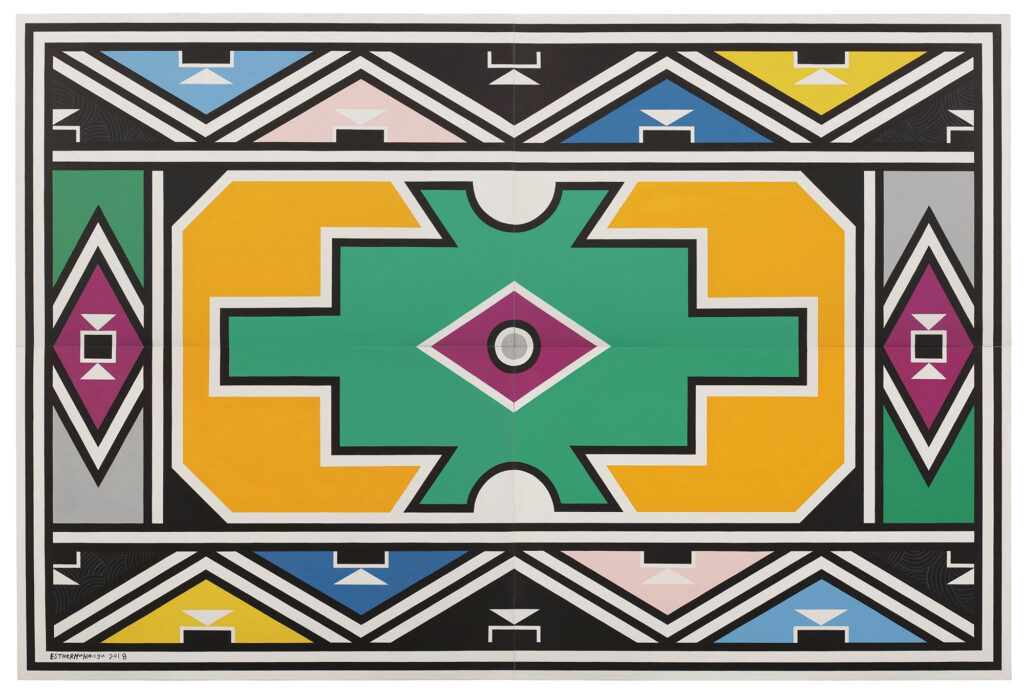

Equally pleasing are Esther Mahlangu’s abstracts based on traditional South African Ndebele house painting, drawing a much-needed connection between the abstraction of patterned indigenous and African folk art and the abstract modernism of 20th-century Europe and North America. It answers the haunting question one might have before a Josef Albers, Picasso, or Paul Klee when one asks, “Where have I seen this before?”

There is plenty of photography too, walls devoted to the historic and iconic photography of Gordon Parks, including famous shots of Muhammed Ali, the iconic portraits of Kwame Brathwaite, and the unflinching street and fashion photography of Jamel Shabazz. In a show this size however, it almost feels tacked on, like an index added to an already massive book. It deserves its own show.

Sculpture is scarce except for the always charming and surreal Nick Cave, who provides a silver suited man being swallowed into a furry circular vortex. The standout sculpture of the show, however, is Arthur Jafa’s “Big Wheel,” a monster truck tire hanging from the ceiling and sheathed in elaborately patterned chains, which packs a visual impact worthy of Theaster Gates.

Layers of conceptual and symbolic nuance are there as well: Mr. Jafa is riffing on Missisppi’s monster truck culture, as well as the State’s more ominous legacies of slavery and anti-Black violence.

Altogether the collection is impressive, even if the presentation seems a bit too flat, too crowded, and a tad too hagiographical towards its sponsors. Every artist in this show is important, the issues are topical and continue to resonate, and there has indeed been a paucity of Black faces in Western art history. The show and the collection itself exist to rectify this very problem, and to that end it succeeds.

Not that deeply serious shows of African American and Afrocentric art are lacking at New York City. Last year we had Barkley l. Hendricks’s astounding portrait retrospective at the Frick Madison, a major show of Njideka Akunyili Crosby at David Zwirner, and Mark Bradford’s massive gallery-wide show at Hauser and Wirth Chelsea. The upcoming Met blockbuster “Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” which opens at the end of next February, promises to be historic.

That “Giants” seeks to edify and uplift with its wealth of relevant contemporary Black art is obvious. Overall, however, the ensemble feels crammed together, less of a nuanced show and more of a wunderkammer for 21st-century pop royalty.