Dead at 98, ‘the King’ of B Movies, Roger Corman, Leaves Behind a Distinctive Legacy

The list of luminaries whose careers Corman set into motion would clog the works of a Hollywood ‘Who’s Who.’

Roger Corman, the American filmmaker affectionately known as “The King of the Bs,” has died at the age of 98. He leaves behind a distinctive legacy as a director and producer, and proved a man of quixotic tastes.

Corman crafted indelible drive-in schlock like “Attack of the Crab Monsters” (1957) and “Creature from the Haunted Sea” (1961), but cited among his favorite films Sergei Eistenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” (1925). Something of a hustler, both in terms of work ethic and pop savvy, he nonetheless saw to the U.S. distribution of films by Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa, and Francois Truffaut. A complicated man, our Roger.

Born at Detroit to a Catholic family, Corman attended Beverly Hills High School and then Stanford University. After serving in the Navy, he earned a degree in industrial engineering, but Corman’s time in that field was short-lived. Within a matter of days he quit his first job with a dramatic flourish, telling his bosses, “I’ve made a terrible mistake.” His next job was working the mailroom at 20th Century Fox.

Corman was incapable of sitting still. Pitching this idea here, learning on that set there, and putting up cold hard cash as a producer, he found his way into the director’s chair, helming a variety of genres: gangster flicks, Westerns, rock ’n’ roll exploitations, sagas about women vikings, and a World War II epic with a tagline that read: “They turned a white hell red with enemy blood.” “Ski Troop Attack” (1960) it was called. An aesthete he may have been during off hours, but Corman knew that sensationalism sold tickets.

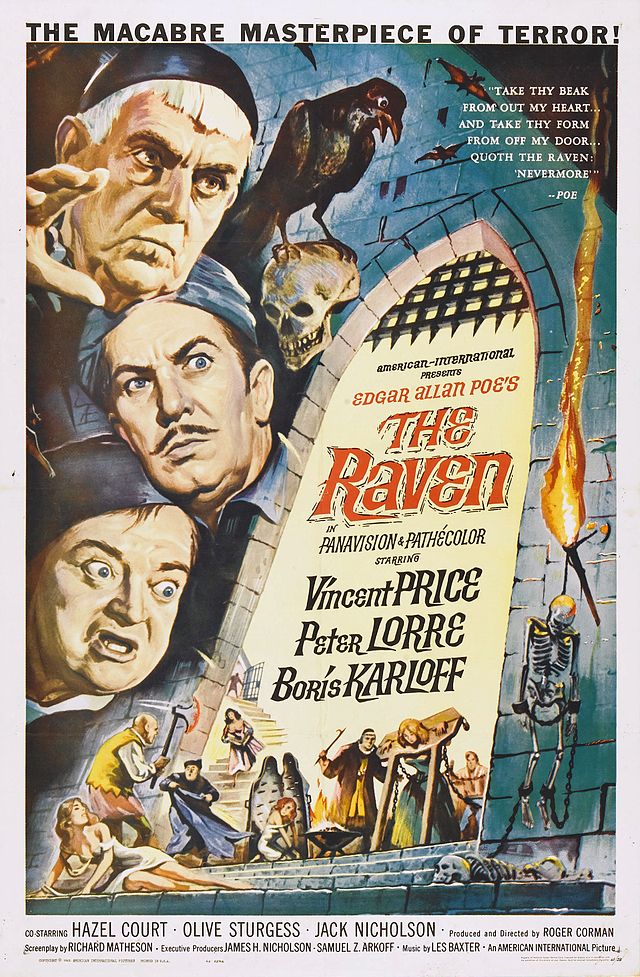

Corman is best known for working fast, working cheap, and working with Vincent Price. A series of period pictures based oh-so-loosely on poems and stories by Edgar Allan Poe proved profitable and cemented Price’s status as a horror icon. Of their seven collaborations, the best are “The Tomb of Ligeia” and “The Masque of the Red Death” (both 1964). The former benefits from location shooting at Castle Acre Priory in Great Britain; the latter, by its wild, almost campy existentialist swing.

Among the tributes that have come down since Corman’s passing is one that’s not much of a tribute at all. On X, the writer and director Paul Schrader cautions movie fans against getting “too sentimental” about Corman: “Roger was better at hyping his rep than at making good films or supporting good filmmakers.” Hyping his own rep is definitely something Corman was good at: You don’t write a biography titled “How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime” without knowing your own strengths.

Still, Mr. Schrader can’t separate his own bitterness from facts-on-the-ground. Corman supported a raft of movie people by (a) giving them a leg-up in terms of experience and (b) famously promising them that if “you do a good job … you’ll never have to work for me again.” The list of luminaries whose careers Corman set into motion would clog the works of a Hollywood “Who’s Who”; they include Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorcese, Jonathan Demme, Peter Bogdanovich, John Sayles, John Cameron, Joe Dante, and Alan Arkush. And those are only the directors.

If Corman helped an aging group of actors keep working during the latter stages of their careers in the 1960s — these included Price, Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre, Ray Milland, and Basil Rathbone — he also provided opportunities for young actors. Among them are Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, Dennis Hopper, Diane Ladd, Sandra Bullock, and William Shatner, star of “The Intruder” (1962). It was the only Corman movie not to turn a profit. The failure of this more personal effort convinced him to stick to what works at the box office.

Corman’s efforts as a producer and distributor contain enough byways to overtax the most diligent of obituary writers. He was awarded an Academy Honorary Award by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2006 and “Fall of the House of Usher” (1960), the first of the Poe adaptations, was cited as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the U.S. National Film Registry in 2005. Accolades will long roll in, but let’s hear from the man himself, summing it up in a typically economical manner: “I was a filmmaker, just that.”