Blu-Ray Edition of Buster Keaton’s ‘Seven Chances’ Offers Opportunity To Focus on Another Big Name From Silent Comedy Era, Clyde Bruckman

Bruckman made a significant contribution to Keaton’s output during the 1920s and co-directed what is considered not only the comedian’s finest film, but one of the greatest films extant, ‘The General’ (1926).

Kino Lorber’s new Blu-ray edition of Buster Keaton’s “Seven Chances” (1925) includes a comedy short starring the Three Stooges, “A Brideless Groom” (1947). What does the stone-faced exemplar of slapstick have in common with the lowbrow shenanigans of the eye-poking trio? The answer is a man who had an important hand in shaping film comedy, Clyde Bruckman (1894-1955).

The era of silent comedy would be very different were it not for Bruckman. A former sportswriter, Bruckman’s earliest gig in the film industry was writing the intertitles for films at Universal Pictures. He moved to Warner Brothers in order to supply gags for Keaton and the two men proved like-minded. Bruckman made a significant contribution to Keaton’s output during the 1920s and co-directed what is considered not only the comedian’s finest film, but one of the greatest films extant, “The General” (1926).

Bruckman’s services were sought after. He directed four shorts that featured Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy at the beginning of their partnership and was a hired hand for Harold Lloyd. Bruckman helmed one of W.C. Fields’s finest features, “The Man On the Flying Trapeze” (1935), and earned glowing reviews from its star, a comedian known to not suffer directors gladly. Perhaps Fields found Bruckman an amenable cohort because Bruckman liked to tipple, a lot.

Drink ultimately got the better of him. Bruckman increasingly found himself relegated to less prestigious assignments. Inspiration, too, seems to have run its course. Bruckman continued to make a living by recycling Keaton and Lloyd routines for marginal talents like the Stooges and Abbott and Costello. Lloyd sued Bruckman several times over “wholesale infringements” and the gagman became desperate and demoralized. Borrowing a gun from Keaton, ostensibly for a hunting trip, Bruckman walked into a Santa Monica restaurant, entered the restroom, and shot himself.

Bruckman was the subject of a biography by Matthew Dessem, “The Gag Man; Clyde Bruckman and the Birth of Film Comedy,” and served as a point of reference on, of all things, an episode of “The X-Files.” So, yeah, Bruckman cribbed from “Seven Chances” for the Stooges, just as he repurposed the billiard game routine from “Sherlock Jr.” for their knockabout Hitler-spoof, “I’ll Never Heil Again” (1941). Appropriating from oneself is all well-and-fine, but Bruckman had to realize the gulf between the breathtaking originals and the cut-rate follow-ups.

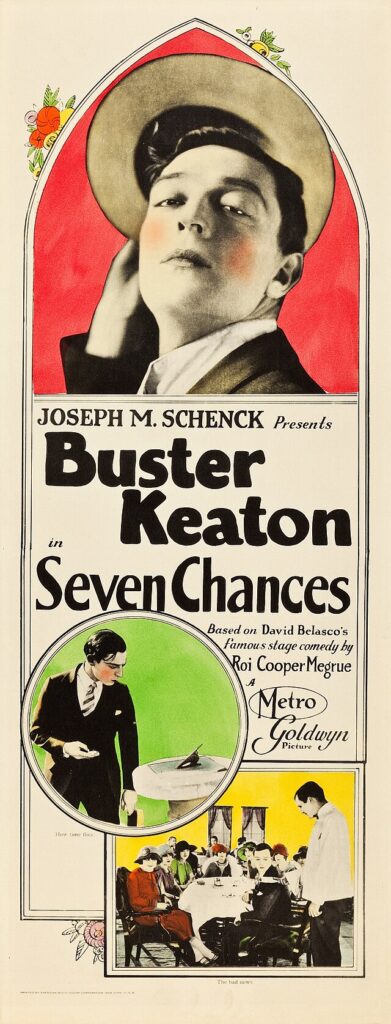

“Seven Chances” was a property that originated outside of Keaton’s purview. Studio executive Joseph Schenk — who was not only Keaton’s business partner, but his brother-in-law — purchased the rights to a hit Broadway play written by Roi Cooper Megrue. Schenk thought it a good vehicle for the comedian, but Keaton found it wanting. He agreed to film the adaptation all the same, largely because he owed Schenk money. The resulting picture proves that artistic skepticism and financial distress can be viable spurs for cinematic magic.

The plot is simple: Jimmie Shannon (Keaton) is a financier in desperate straits. When informed by his lawyer (Snitz Edwards) that he’s inherited $7 million from a distant relative, Shannon and his partner (T. Roy Barnes) breathe a sigh of relief. There is a catch, of course: the endowment is contingent upon Shannon being married by 7 p.m. on his 27th birthday. You’ll never guess what day it is when all-and-sundry receive the news. Another rub is that the better part of that day is gone.

Should the set-up ring a vague bell, it’s because the plot was the basis for Gary Sinyor’s “The Bachelor” (1999). The Renee Zellweger vehicle was a modest box office hit, as was the Keaton original. In artistic terms, however, “Seven Chances” can’t be beat. Although it’s marked by the brief use of ethnic stereotypes — a cultural given that Keaton undermined as much as coasted upon — the picture is a stunning, typical Keatonian endeavor in which slapstick and surrealism find a happy medium. It’s funny, it’s thrilling, and is never less than brilliant.

In other words: another Keaton masterstroke. We should all be so inspired.