‘Bizarro Defined’: Salt Lake City’s Gilgal Sculpture Garden Beguiles as an Art Destination

The park, created by a Mormon outsider artist, today serves as a respite for those who prefer the sacred when leavened with a dollop of quirk.

Salt Lake City has any number of attractions that should pique the interest of seasoned travelers. The hub of the Mormon Church and self-avowed site of “wholesome activities,” Temple Square, has limited access due to an ongoing “seismic upgrading.”

Tracy Aviary, though, located in expansive Liberty Park and one of only two accredited aviaries in the United States, is open for business. A number of natural splendors are available just a short drive outside of the city proper. And then there’s the world’s greatest bookstore, Ken Sanders Rare Books. Then again, I came of age in the place. My bias is a matter of local pride.

Among the more curious destinations of a city known to be curious by gentiles — that is to say, those who don’t belong to the Mormon faith — is squirreled away in a side street not a stone’s throw from a high-end shopping emporium, Trolley Square, and around the block from a cornerstone of Salt Lake gastronomy, Hires Big H drive-in.

Though there are many historic sites that mark the trek made by Mormon pioneers and their establishment of a religious center, none are as odd as the Gilgal Sculpture Garden.

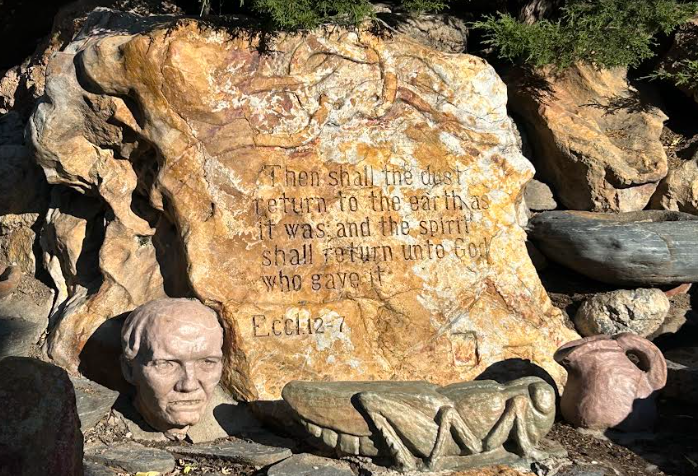

The name of the sculpture garden will strike a chord to those familiar with the Hebrew Bible. In the Book of Joshua, Gilgal is the location at which the Israelites camped after crossing the Jordan River. The travelers gathered stones — twelve of them, to be precise — and set them up as a memorial to the miracle-dotted trek.

Depending on where you park your bookmark — here in the Book Of Samuel; there in the Book of Deuteronomy — Gilgal takes on different guises. Thomas Battersby Child, Jr. (1888-1963), a building contractor and a Bishop at the local ward of the Latter-Day Saints Church, went with the Book of Joshua.

Gilgal is also mentioned in the Book of Mormon as one of the cities that suffered divine retribution upon the crucifixion of Christ.

Mix the Old Testament, the Book of Mormon and then add myths culled from antiquity and you have an art destination that is, devotionally speaking, a little bit of this and a little bit of that.

The park’s signal sculpture is a sphinx that bears the likeness of Mormon church founder Joseph Smith. This particular homage to a scion of American spiritualism is, to pinch a phrase from Winston Churchill, a riddle, a mystery and an enigma.

Child was making a sincere declaration of faith upon crafting the Smith sphinx, but that hasn’t stopped internet wags from classifying it as “bizarro defined” or “patriarchal cult art.”

The Gilgal Sculpture Garden is, admittedly, far removed from the artwork that predominates at the Church History Museum just a few miles away. No neoclassical artist, Mr. Child, and not a lick of training either.

He just up and started shaping stone at the age of 57, sometimes with the help of Utah sculptor Maurice Brooks and often with tools that weren’t to the metier born — most predominantly, an oxyacetylene torch. Like most outsider artists, Child used what he had on hand.

Among the other sculptures on display are a shrine to Child’s wife Bertha, an oversized agglomeration of disembodied body parts that is King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream and a totem that is a lumpish combination of Assyrian reliquary and Chinese scholar’s rock.

After Child’s death, his visionary haven went largely unattended, frequented mostly by teenagers needing an isolated space to smoke weed.

Thanks to funding from Salt Lake County, a local arts foundation and the LDS Church, the Gilgal Sculpture Garden was brought up to snuff in the year 2000 and now serves as a public park, as well as a respite for those who prefer the sacred when leavened with a dollop of quirk.

Child averred that “you may think I am a nut, but I hope I have aroused your thinking and curiosity.” In that regard, his legacy is set in stone.