Based on Actual Events, ‘Vladimir’ Traces Life in Russia Under the Leadership of Its Violent, Corrupt President

Playwright Erika Sheffer sustains an air of suspense that’s predictably well served by director Daniel Sullivan and his fine cast, who deftly mine the play’s ample humor.

One of the most compelling new plays of last season, “Patriots,” traced the rise of Vladimir Putin and featured the Russian leader as a principal character. In Erika Sheffer’s “Vladimir,” now having its world premiere off-Broadway, the title figure never appears onstage, but Mr. Putin’s presence is as constant as it is menacing.

Ms. Sheffer, whose own family moved to America from the Soviet Union in 1975, made an auspicious debut a little more than a decade ago with “Russian Transport,” which followed Russian Jewish immigrants forced to confront moral questions when a visiting relative offered a shady path to prosperity. In “Vladimir,” the action unfolds at Moscow in 2004, as Mr. Putin is, by dubious means, elected president — we see him first appointed to that office, by an enfeebled Boris Yeltsin, in a prologue set in 1999 — and sets about entrenching and expanding a leadership marked by violence and corruption.

One woman, it seems, is determined to stand in his way: a fearless journalist named Raisa Bobrinskaya. Like the real-life investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya, who was assassinated in 2006, Raisa — or Raya, as she is called here — has earned both acclaim and dangerous enemies through her work, including her coverage of the second Chechen war. When we first meet Raya, she is recovering from injuries apparently sustained on the job; suffice it to say it won’t be the last time her health suffers in the play, with the government implicated.

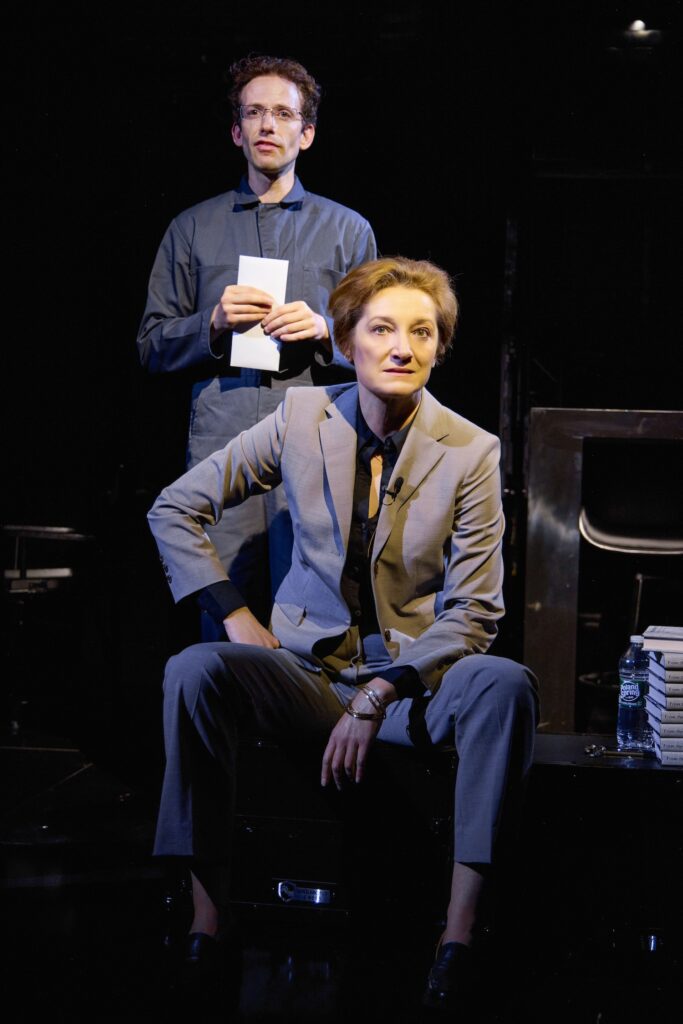

Played with a quiet but fierce dignity by Francesca Faridany — who speaks in a tight, hoarse voice that conveys both weariness and resolve — Raya approaches her profession with the all-consuming zeal of a martyr. Her editor at a Moscow newspaper, Kostya, is more pragmatic; wittily portrayed by the Broadway star Norbert Leo Butz, he also has an acute social conscience, but possesses a keener sense of self-preservation, not to mention a taste for worldly pleasures.

With Mr. Putin tightening his grip, and the paper’s editorial integrity looking increasingly vulnerable, Raya and Kostya are drawn in opposite directions: He’s tempted to take a job at a state-run television station, while she learns about an American company that has just received the largest tax refund in Russian history and, smelling a rat, wants to pursue the story.

A financial analyst named Yevgeny becomes Raya’s source; inspired by a whistleblower who died in a Russian prison in 2009 at the age of 37, Sergei Magnitsky, he is reluctant to get involved at first. When Raya accuses him of apathy, he insists, “I’m not apathetic, I’m afraid.” She responds, “You think you’re afraid, because you’ve been trained to be.” Yevgeny counters, “What’s the difference between thinking you’re afraid and actually being afraid?”

The dialogue remains crisp and thoughtful as Raya’s investigation and Kostya’s career path lead to more inner turmoil for both. Another story lifted from past headlines, the Beslan massacre of September 2004 — in which Chechen militants stormed a Russian school, leading to the deaths of more than 300 people, including more than 180 children — exacerbates their feelings of conflict: Kostya is repulsed to learn his employers may be concealing an advance warning, while Raya is haunted by the prospect that people she had seen as victims could be capable of such monstrous actions.

Ms. Sheffer makes these quandaries vivid, and sustains an air of suspense that’s predictably well served by director Daniel Sullivan and his fine cast. David Rosenberg’s gentle, noble Yevgeny, who still carries the scars of the anti-Semitism he suffered as a youth, gets a clever foil in his character’s American boss, Jim, a crass businessman who has learned to play down his own Jewish heritage just as he’s buried his scruples. Jonathan Walker is convincingly brash in the latter role, and like the other actors, he and Mr. Rosenberg deftly mine the play’s ample humor.

Mr. Walker is one of several performers who juggles other roles. They also include Erik Jensen, who exudes casual cynicism as an old friend of Kostya’s who has become a Kremlin official; Olivia Deren Nikkanen, tender but sturdy as Raya’s concerned daughter; and Erin Darke, bitter and moving as a young Chechen woman who lingers in the journalist’s thoughts long after she has left the field.

“I’m helping, I’m doing something useful,” Raya protests, during one of a few scenes in which this woman climbs inside her head; the reporter is, of course, trying to convince herself as much as anyone else. She might as well be attempting to move a mountain, but in this briskly absorbing play, her dedication is something to behold.