As ‘Frankenstein’ Edges Toward Its Centennial, Universal Studios Offers a High-Definition Restoration

What is there left to say about this seminal horror picture? At a time when practically anything that draws breath is labeled ‘iconic,’ here’s a film that has earned the honorific.

Universal Studios has just released a steel book edition of James Whale’s “Frankenstein” (1931) that is being touted as an “ultra high def 4-K restoration.” For what occasion this gussied-up package has been manufactured isn’t clear, though the marketing folks at Universal likely have something in mind for the 100th anniversary of the film a mere seven years from now. The current set has a handsome black-and-white illustration by a comic book artist, Alex Ross, that will be hard to top.

What is there left to say about this seminal horror picture? At a time when practically anything that draws breath is labeled “iconic,” here’s a film that has earned the honorific. Popular culture is unimaginable without the precedents set into motion by Whale’s movie: a scientist playing God, a patchwork monster, a hunchbacked assistant, villagers wielding torches and pitchforks, and — a particular favorite of mine — a Mitteleuropean locale populated by an abundance of Englishmen.

Mary Shelley’s novel — the subtitle of which, it behooves us to remember, is “The Modern Prometheus” — was filmed three times before the founder of Universal Studios, Carl Laemmele Jr., signed off on doing so. Two of the silent versions have been lost, but not the 1910 edition made under the auspices of Edison Studios. At 16 minutes in length, it makes swift work of “Mrs. Shelley’s famous story.” The monster, as portrayed by Charles Ogle, dissipates into the ether upon seeing itself in the mirror.

At this date, it’s difficult to get a sense of the sensation Whale’s “Frankenstein” caused upon its initial release. Contemporary viewers will note that the credits, in true patriarchal fashion, cite the author as “Mrs. Percy B. Shelley.” Yet that doesn’t account for the trigger alert we’ve already sat through — a segment in which actor Edward Van Sloan comes out from behind a curtain to advise us that “if any of you feel that you do not care to subject your nerves to such a strain, now’s your chance to uh, well — we warned you!”

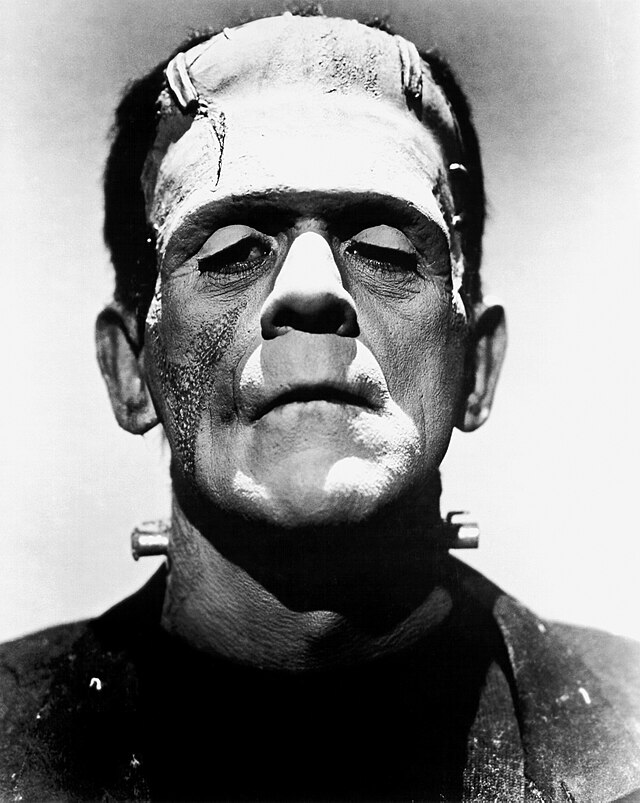

The screenplay for “Frankenstein” was based on a stage adaptation by a British poet, Peggy Webling, and subsequently massaged by a variety of hands, including the director originally pegged to helm the picture, Robert Florey. When Universal gave Florey the boot, it did the same for the actor he had screen-tested, Bela Lugosi. When Whale got the assignment, he spied an actor in the studio commissary and thought him a perfect monster. And so William Henry Pratt, known professionally as Boris Karloff, signed on for the role.

The 42-year old Karloff had been kicking around Hollywood for a while. “Frankenstein” was his 82nd film, and it was a game changer. Although Karloff had been gaining more prominent parts — his role as a convict in Howard Hawks’s “The Criminal Code” (1931) was particularly noteworthy — his take on Shelley’s “hideously ugly creation” not only garnered the journeyman actor stardom, but immortality. Karloff considered the monster “the best friend I’ve ever had.” The life of an actor can be hard; the soft-spoken Briton was grateful for his Frankensteinian stroke of good fortune.

How well does the film hold up? There are slack patches of logic in an already fanciful plot, and Whale’s fondness for British archetypes — here seen in the guise of a blustering Frederick Kerr as père Frankenstein — can be trying. But the director sustains a strong sense of mood, an effort in which he received immeasurable help from set designers Charles D. Hall and Kenneth Strickfadden. Colin Clive is unconvincing when romancing Mae Clarke, but he’s as manic as he needs to be when he’s in the laboratory sinning against nature.

As for Karloff: His performance as a murderous and misunderstood monster has become more heartbreaking over time. He would reiterate the role two more times, in Whale’s defiant sequel, “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935), and Rowland V. Lee’s Expressionistic “Son of Frankenstein” (1939). Yet there’s something to be said for first impressions. “Frankenstein” will be haunting our imaginations for years to come.