Arriving From Across the Pond, Jez Butterworth’s ‘The Hills of California’ Is Theater at Its Best

The production is the playwright’s first on Broadway since 2018’s ‘The Ferryman,’ another London import that also featured the luminous Laura Donnelly and a star director, Sam Mendes.

On Broadway, it’s shaping up to be a big season for stage mothers. In just a couple of months, audiences will have the opportunity to see Audra McDonald tackle Mama Rose, the Medea of musical theater, in a new revival of “Gypsy.” Also, a new character that’s every bit as substantive and painfully mesmerizing is making her New York debut right now.

That would be Veronica Webb, the matriarch at the center of Jez Butterworth’s magnificent, devastating “The Hills of California,” which arrives after earning Olivier Award nominations for Mr. Butterworth and leading lady Laura Donnelly across the pond. The production is the playwright’s first on Broadway since 2018’s “The Ferryman,” another London import that featured the luminous Ms. Donnelly, Mr. Butterworth’s offstage partner, and earned Tony Awards for best play and for its star director, Sam Mendes, who also helms “California.”

Those credentials alone may not prepare you for the technical mastery and emotional wallop of this play and Mr. Mendes’s production, set in the coastal town of Blackpool in northwestern England. Over two hours and 45 minutes, minus an intermission and a brief pause — Mr. Butterworth’s works are not known for their brevity — “Hills” shifts between 1955, when we watch Veronica try to groom her four young daughters into an Andrews Sisters-like singing act, and 1976, when those daughters, now grown women, essentially wait for their mother to succumb to cancer.

“Hills” was inspired in part by Mr. Butterworth’s family history, including the death of his sister from cancer more than decade ago. Yet the play also explores a subject that’s at once topical, particularly in the context of show business, and timeless: the exploitation of women, and the vicious cycles that can make women themselves seem complicit or unsympathetic to their sisters.

As “Hills” focuses on sisters by blood, and their mother, the dynamics here are especially fraught. Veronica, whom we meet as a widow in her late 30s — we never see her as she is dying, though her pitiful condition is revealed through her daughters’ descriptions and reactions — comes across at first as steely and hyper-efficient. A relentless taskmaster to her girls, who are drilled not just as performers but as Andrews Sisters historians, she also runs a boarding house, designed to sprawling, dilapidated splendor by Rob Howell, another “Ferryman” alumnus.

Grandly titled the Seaview Luxury Guesthouse and Spa — a running joke is that there’s no view of the sea — the resort is divided into guest rooms named after American states, reflecting Veronica’s aspirations. “I want them to live,” she says of her daughters. “To soar.” Like many such women, and men, Veronica does not see herself as trying to prosper vicariously through her children; she is utterly devoted to them in her fashion, however misguided her methods or goals may be.

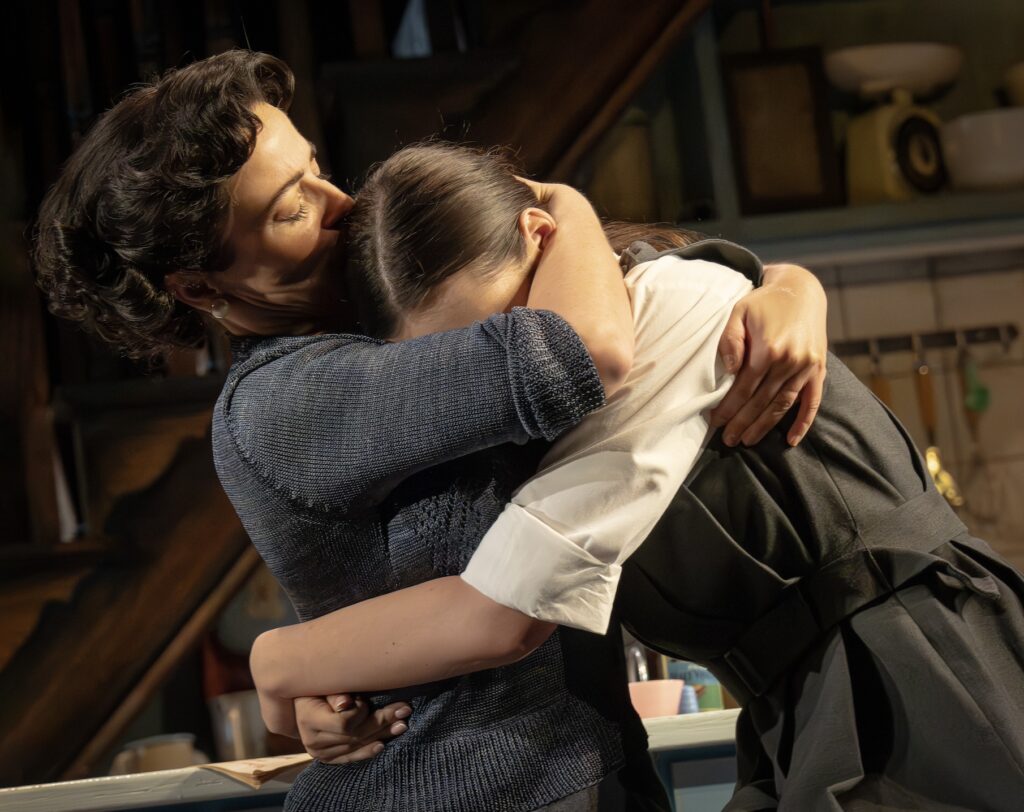

This is made shatteringly clear in a pivotal scene in which a talent agent, an American man, arrives to audition the girls — and decides he is only interested in one of them. The passage delivers one gut punch after another, as Ms. Donnelly brilliantly evokes a storm of ambition, fear, and guilt, while David Wilson Barnes, as the visitor, delivers some of the coolest, most subtle menace I’ve ever witnessed, on stage or off.

Ms. Donnelly also plays the chosen daughter, Joan, as an adult, who has managed to make it to the United States — although not through a path Veronica had envisioned — and returns only after two decades of no contact with her mother, sounding like a Californian and sporting an elaborate hippie wardrobe. Making a dramatic entrance to a cleverly selected Rolling Stones classic, she elicits mixed reactions from her siblings; the virginal Jill, who has remained at home with Veronica, is rapturously grateful, while Gloria, as caustic as Jill is angelic, fairly boils over with resentment.

If the sisters, who also include the feisty but sensitive Ruby, seem to fit neatly contrasting personality types, the dialogue and the superb performances — by Helena Wilson, Leanne Best, and Ophelia Lovibond as, respectively, Jill, Gloria, and Ruby — flesh out the characters beautifully as their complicated history is uncovered. Richard Lumsden, Bryan Dick, and Richard Short are equally nimble and affecting as an assortment of men who figure into their lives, most of whom offer empathy, along with some comic relief.

The four actresses cast as the young sisters — Nancy Allsop, Sophia Ally, Lara McDonnell, and Nicola Turner — are likewise excellent, though I doubt their character arcs will leave any aspiring performers with stars in their eyes. Both in spite of that and in part because of it, “The Hills of California” is essential viewing for anyone who loves theater.