A Searing New Film, ‘The Seed of the Sacred Fig’ Portrays the Oppression and Fear of Living Under the Iranian Powers That Be

Director Mohammad Rasoulof’s masterly focus on a divided family echoes the passionate appeals of women and young people everywhere, though the film is firmly rooted in the struggles of the Iranian people.

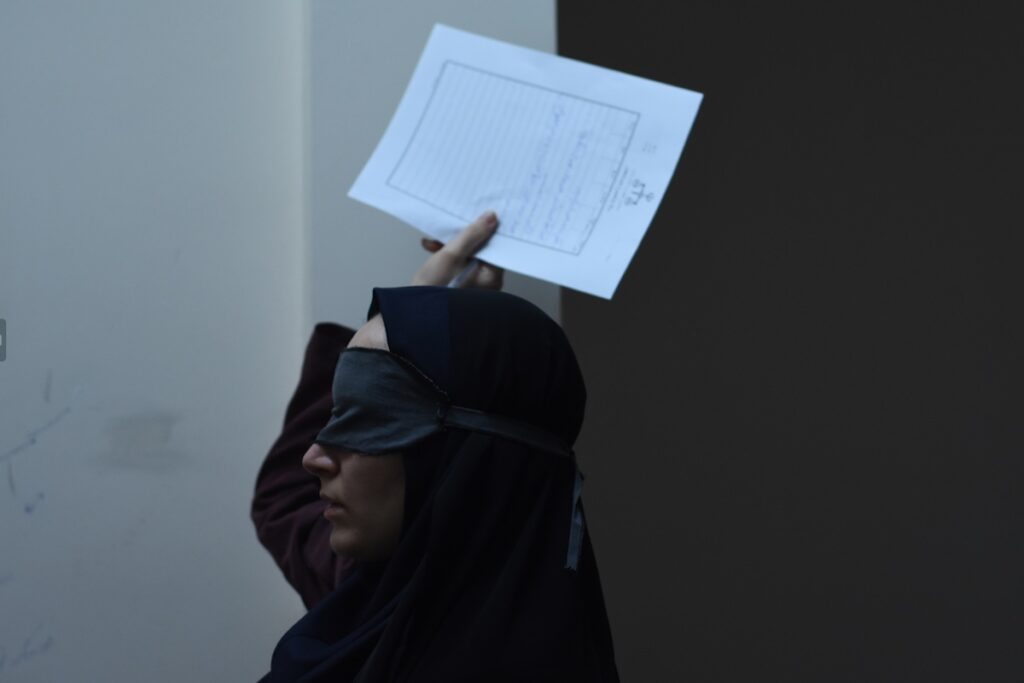

The 2022 death of a young Iranian woman, Mahsa Amini, after apparently wearing her hijab incorrectly and the resulting protests that rocked the country provide the new Iranian film “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” not just with its backdrop but also with its metaphorical inquiry: How can a family survive on the suppression of expression, or, in other words, on secrets and lies? It’s an incisive question given trenchant treatment by writer/director Mohammad Rasoulof, who fled Iran this year before appearing at the Cannes Film Festival in May for the movie’s world premiere.

An atmosphere of oppression and fear permeates the film from its very start. Husband and father Iman has been promoted to investigator in Tehran’s Revolutionary Court, with the hallways of the office building in which he works lined with eerie, lifesize placards of government officials. Despite a higher salary, his new position comes with clear downsides: Because court officials are often threatened he is given a gun as protection, while his wife Najmah and daughters Rezvan and Sana must conduct themselves with utmost moral rectitude and humility. The girls’ social media use comes in for particular scrutiny, as does an outspoken friend, Sadaf.

Even though Iman works for a shadowy, repressive institution, he is not a wholly unsympathetic character. When a work colleague urges him to sign a death sentence indictment, he responds that he hasn’t read the accused’s file and thereby feels he cannot endorse the judgment. His family continues much as before, with the girls largely unaware of what his job entailed prior to and since his promotion; housewife Najmah wishes for a dishwasher and the girls desire thinner eyebrows and tighter-fitting overgarments. The real change comes when the unrest begins.

As footage of the protests and riots that followed Mahsa Amini’s killing at the hands of the government airs on television, Najmah and her daughters take up opposing sides regarding the events, with the mother agreeing with the government’s stance and reaction and the sisters condemning the suppression of outrage and criticism. It’s on social media where the most graphic imagery of the brutal crackdown can be viewed, and director Rasoulof makes ample and potent use of real-life footage from the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising.

When Sadaf is struck with pellets while in the streets, Mr. Rasoulof presents us with a poignant yet disturbing scene of Najmah administering first aid to the girl’s face. This scene is soon followed by a similar one: of Najmah cutting her husband’s hair, shaving him, coloring his beard, and moisturizing his skin. The contrast couldn’t be clearer: Iranian women can expect to be shot in the face for the slightest transgression, while Iranian men require women’s obedience and lavish attention at all times.

An argument between older sister Rezvan and her father during a family dinner brings to the forefront the debate over patriarchal superiority. While they occasionally dispute details specific to Iran, the characters’ dialogue could have been lifted from any dinner table across the world. Mr. Rasoulof’s masterly focus on a divided family echoes the passionate appeals of women and young people everywhere, though the film is firmly rooted in the struggles of the Iranian people, particularly women, against the authoritarian forces of the Islamic Republic regime.

This domestic drama/familial divide, exacerbated by the turmoil happening just outside their windows, soon becomes a canyon of distrust after Iman’s firearm goes missing, jeopardizing his job. He believes someone in the family has taken it, while his wife alternates between thinking that he could have misplaced it or suspecting Rezvan. Mr. Rasoulof’s twist on the “Chekhov’s Gun” rule is just one of several mordant bits of humor in an otherwise serious, anxiety-ridden viewing experience.

The central cast members playing the four family members are compellingly naturalistic in handling their roles, even if a few instances of wooden line readings creep in. Whether this slight stiffness purposely reflects the rigidity of Iranian society or might have arisen from the illicit nature of the film’s production is unclear. What is without doubt, though, is their commitment to the story being told, even as some of them, like Missagh Zareh and Soheila Golestani, who portray the parents, could be thrown in prison for remaining in Iran after working on the project.

As the family grapples with the missing gun, the film transforms into a paranoid thriller, with several distressing sequences, such as when Najmah and the girls attend a therapy session-cum-interrogation, and when Iman, with his family in the car with him, races after another vehicle being driven by agitators. Once they arrive at Iman’s rural childhood home in the picture’s third hour, a certain impatience with the pace and even some plot skepticism sets in, though this last act’s mix of familial closeness and dread does include surprises and indelible images.

A remarkable cinematic artwork across the board, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig” deserves praise for all of its audacious achievements: the bravery of its director, cast, and crew in completing the film under duress; its lucid message of liberty and defiance; and, finally, the haunting quality of its storytelling and visuals.