A Glimpse Into the Origins of the ‘Pictures Generation’ Fomented by Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo

A new show contains rarely-seen archival material, artworks, video, and film from the movement that would eventually explode into the circus of the 1980s art world.

‘Pictures Generation: From Hallwalls to the Kitchen and Beyond’

Sara’s at Dunkunsthalle

64 Fulton Street, New York, New York

Through November 2, 2024

If you are wondering where art titans Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo got their start, you need go no further than the Dunkunsthalle on Manhattan’s Fulton Street. Once a couple sharing a loft in the Financial district in the late seventies, they fomented a movement called the Pictures Generation.

Curated by Vera Dika as part of a curatorial residency and hosted by the nearby Sara’s gallery, this new show contains rarely-seen archival material, artworks, video, and film that give an early glimpse of the movement that would eventually explode into the circus of the 1980s art world. Ms. Sherman would go onto art superstardom, and Mr. Longo would go on to achieve equal renown — and even direct a blockbuster feature film.

The current show is devoted to the early years of the group, whose core members — Mr. Longo, Charlie Clough, Ms. Sherman, Nancy Dwyer, and Michael Zwack — all began their careers at Buffalo’s Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center. It was shortly after this debut that Mr. Longo and Ms. Sherman moved to 85 South Street at New York, just a stone’s throw away from the exhibit space. The show can be seen as a double tribute to Hallwalls, now celebrating its 50th anniversary, and the surrounding financial district that birthed it.

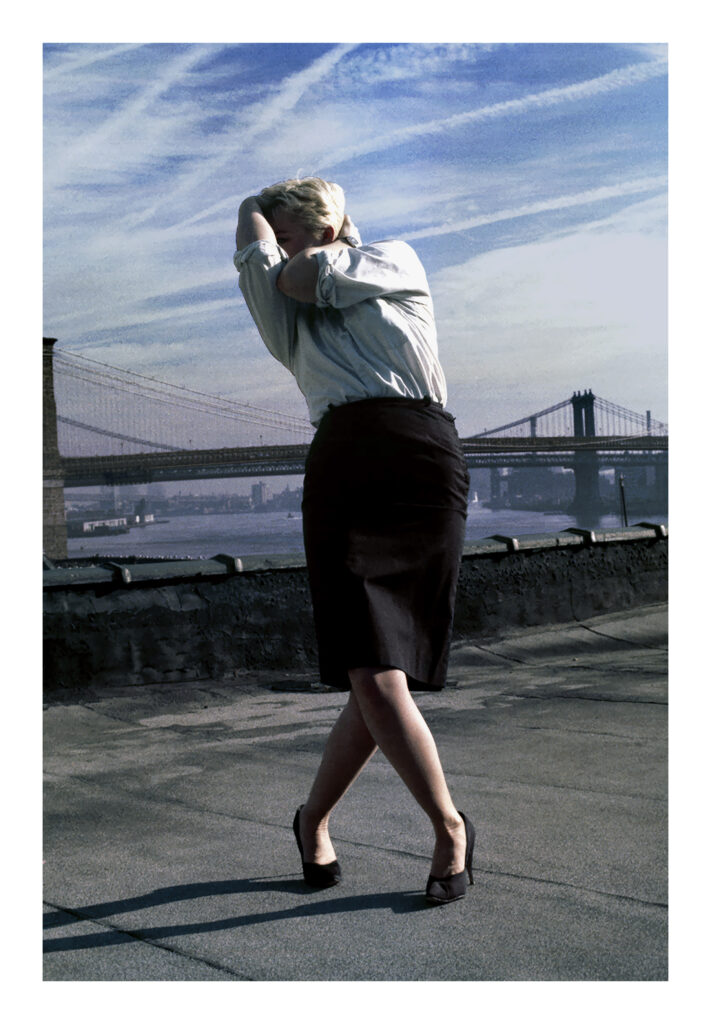

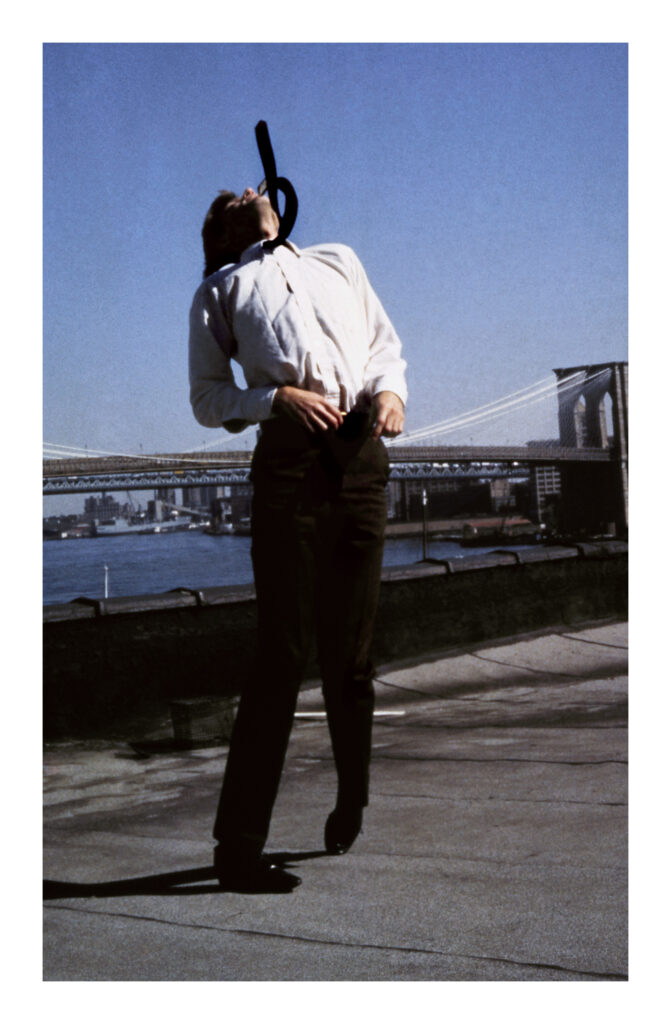

The show itself is a savvy collection of works and ephemera from the group’s early years. Mr. Longo’s signature urban jumping figures, iconic in their dynamism, were years ahead of their time. Their dynamism, however, is not so much joyful as it is convulsive. This is the undercurrent of dysphoric anxiety, even compulsion, that sets the Pictures Generation apart. These photographs, taken on the roof of a nearby building, would later become reproduced by Mr. Longo as hyperreal drawings and launch a new phase of his art career.

Other artifacts include Jack Goldstein’s acquired pieces of media, such as a sound effects record found in a studio effects library. “The Six Minute Drown” is a vinyl record which contains a recording of an actor drowning for three minutes on each side. Once again, the use of found media and deep discomfort are the order of the day — the record was played as a background for some of the group’s early performance pieces. There are also Goldstein’s framed handwritten notes on the importance of distance in art, and another typed text piece containing the sentence “I was so lonely I had to get on a bus that was full of people.” Once again, we see this new generation of artists nearly returning to the anxiety of existentialism.

Which makes sense. Emerging hungover from the utopian designs of the 1960s, the Pictures Generation found themselves addressing something of a void in American contemporary life. The plethora of alluring, stylish, and sexy imagery that went along with general prosperity seemed to be ascendent, but it appeared to be floating over a great moral void, not to mention a New York City in late 1970s decay. We get the sense that the ethos behind the American dream had cracked. This explains Ms. Sherman’s restless shuffling from persona to persona, perfecting each one but never settling, a restless channel surfer of identity.

A vitrine of different artifacts in the center of the exhibit conveys a similar inability to settle. We see two Sherman photographs, an ingenue pose and another dressed as a no-nonsense Mrs. Santa Claus, in white wig and heavy prosthetics. There are text pieces, zines, and other publications in the vitrine with scripts alongside them, showing the generations indebtedness to text and film. There is a constant exploration of art by any other means than drawing, painting, or sculpture, in other words.

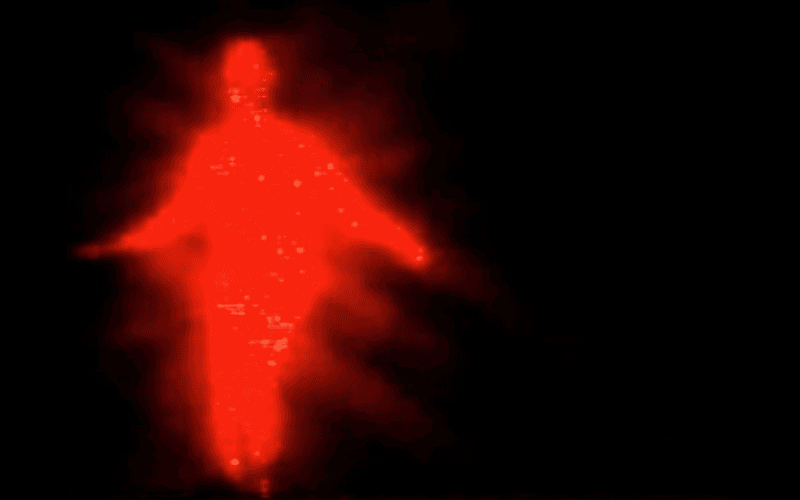

The back room, in the meantime, features several experimental video pieces. Ms. Sherman performs, in black and white and suitably didactic and dry, placing and removing objects from a light-filled box. Then there are Goldstein’s bright rotoscopic renderings of gymnasts and dancers in his signature video “The Jump”: Dynamic figures leaping and pirouette across the screen, each made up of what appear to be colored LED traffic lights. Once again, we have a new kind of colorful and restless energy. Not affirmative, necessarily, but bursting to get off the screen.

The early experiments documented here would lead to many other projects in the art world and beyond. Mr. Longo has gone on to enjoy a long career which detoured into film making. His first directorial attempt, the adaptation of the William Gibson short story “Johnny Mnemonic,” starred Keanu Reeves and opened to mixed reviews, though its ambitious attempts at futuristic world building have won over critics in retrospect.

A screening of short films by Goldstein, Ms. Sherman, Mr. Longo, and Gretchen Bender is showing at the Roxy Cinema. A screening of “Johnny Mnemonic” in black and white, and including a conversation with Mr. Longo, will take place at the cinema on October 28.