A Closer Look at James Welling and John Wesley, Two Artists Who Defy Classification

An inability to be pigeonholed has allowed both artists to doggedly pursue their own idiosyncratic practices.

James Welling: ‘Thought Objects‘

David Zwirner, 533 West 19th Street, New York NY

January 11 – February 10, 2024

John Wesley — “WesleyWord: Works on Paper and Objects 1961-2004”

Pace Gallery, 540 West 25th Street, New York, NY

January 12 – February 24, 2024

Two prominent Chelsea galleries are featuring retrospectives of artists who defy classification. In the inaugural stretch of the January art season, at David Zwirner, we have a photographer who cannot be strictly classified as a photographer, James Welling. We also have, at Pace, a pop minimalist painter who refuses to fit neatly within the confines of the genre, John Wesley. This inability to be pigeonholed has allowed both artists to doggedly pursue their own idiosyncratic practices.

The Welling exhibit opens today with a multi-room retrospective at David Zwirner. Mr. Welling has long challenged what can be formally classified as photography, working at the intersection of photography, collage, digital art, and printmaking.

People are never physically present in Mr. Welling’s photographs, yet the human eye is forever implicated. At first glance, they appear to be formalist studies of architecture, along the lines of Bernd & Hilla Becher or their main disciple, Andreas Gursky. Looking closer, however, leads to disorientation, if not confusion.

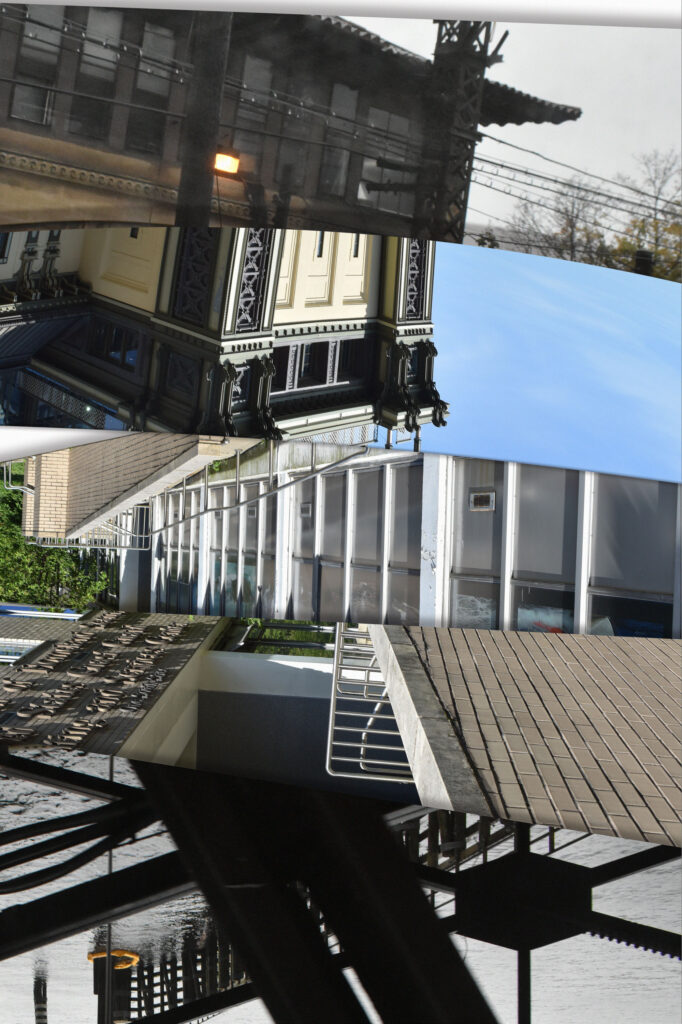

In some images, for instance, he enjoys taking elements of different photographs and collaging them together, as in his photograph of the Salk Institute, where he composites several different photographs of the building in strips, disrupting its unified aesthetics and creating something different. Others graft images of buildings directly onto objects, as he does in “Cubi XXII,” not included in the Zwirner show, where he digitally collages photos of a Yale campus building directly onto a stainless-steel David Smith sculpture.

His piece “The Battery” similarly takes strips of different architectural photographs, some of which are inverted completely, to give us a topsy-turvy and collaged vantage point that upends our stable sense of place and orientation.

The process is subtly, and in some cases profoundly, disorienting. In other prints, he adds rough and printed textural elements, reminding us that the photographic image, no matter how seductive, is merely a screen through which external reality is perceived.

In his floral prints, he uses the unique textural properties of UV-curable ink on Dibond aluminum to create a vivid three-dimensional effect that appears almost hyperreal at a distance. In that sense, his work is a searching and continuous investigation of the formal limits of human perception, the legibility of the image, and the material components that bring it to life.

In the third-floor retrospective of Wesley at Pace, people are present, but there is a similar asperity to his approach. Something vaguely sinister is always afoot in each painting, which nonetheless also manages to be funny. With their deadpan wit delivered in a muted palette of powder blue, baby pink, cool green, and beige, they resemble wry storybook pictures torn out of dystopian fairy tales.

Originally an aviation engineer, Wesley infused his art with clean, diagrammatic aesthetics. This orientation towards the graphic continued when he worked at a Postal Office, such as his outline of an Indian head and or the silhouette of a plane. He was also fond of grouping his subjects in triplicate, creating images that recall advertising. They always manage, however, to hint at something more unsettling.

“Blue Blanket,” which is a late work, shows a man and a woman in the middle of some type of negotiation. Its intricacies aren’t ours to fathom, though they appear to center around the blanket. “Sleeveless Sweater” raises similar questions, as the nude woman wearing it appears to be addressing someone with a pointed glance. Who is she looking at? Why the hand on her hip? What the hell is going on? The incredibly pleasing and harmonized colors of the piece only help to augment the psychological ripples undulating under the surface.

Though he spent much of his career at New York City, Wesley was born at Los Angeles and infuses his art with a distinctly Californian, cinematic quality. One has the feeling of being caught mid narrative, and I couldn’t help but continuously think of stills from the films of Robert Altman: highly stylized figures embroiled in mildly absurd psychodramas.

There are also references to advertising and pop culture, which often caused Wesley to be grouped alongside other “pop” artists such as Roy Lichtenstein and Tom Wesselmann. His ability to convey psychological oddity and depth, however, makes it difficult to group him with his much cooler contemporaries. His “Homeless Bumstead” — Dagwood was a life-long preoccupation of his— shows the titular leading man asleep against a lamp post, with all the equanimity of a Zen sage.

Wesley, who died at the age of 93, had a long and relatively reclusive career that nonetheless was championed by shinier luminaries in the art world. He was consistently championed by minimalist sculptor and art world titan Donald Judd. He never languished in obscurity but remains a lesser-known gem who practiced his own off-beat craft.

Together both shows — though radically different in style and approach — speak to artists who stubbornly refuse classification, resulting in unconventional trains of visual thought. We might call it a blessing in disguise.

_______________

This piece has been updated to reflect a change in the lineup at the exhibit of works by James Welling.