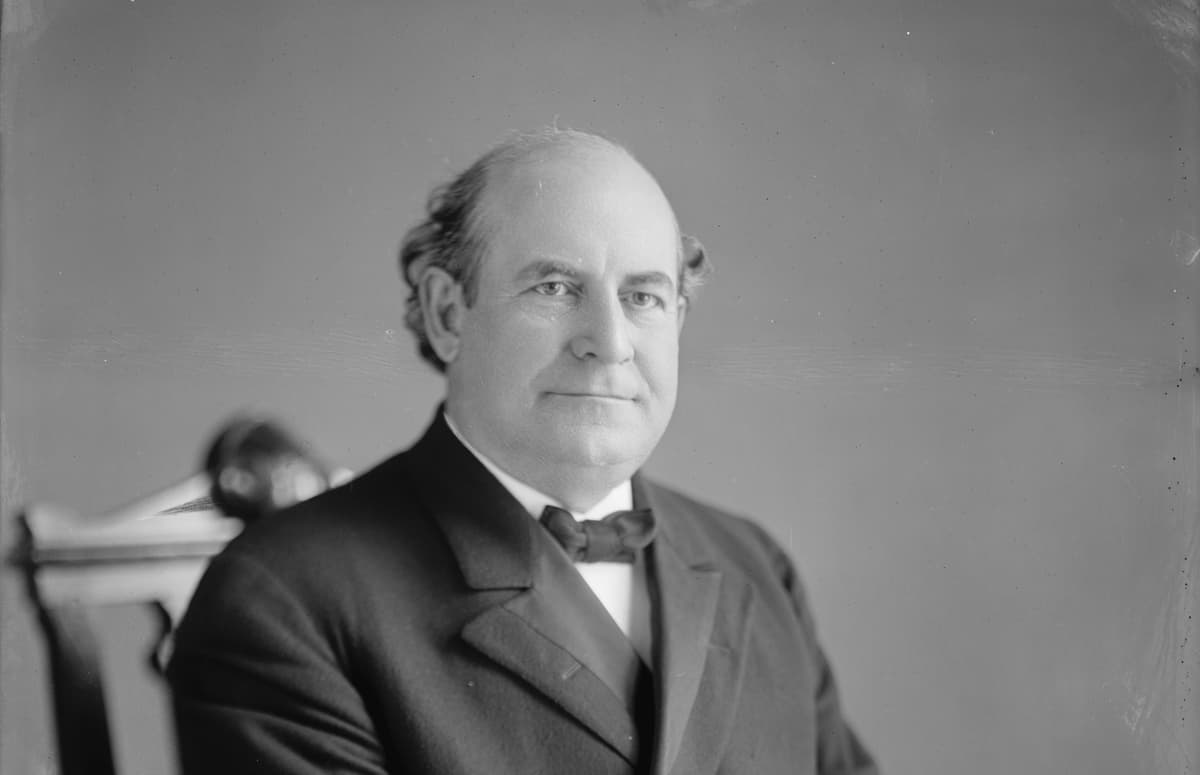

William Jennings Trump?

This is the first time since 1896 that a presidential candidate is campaigning for a weaker dollar.

The idea that President Trump might — might — run on the platform on which William Jennings Bryan got defeated by William McKinley is, if you ask us, the big news out of Milwaukee. It is being mooted by both President Trump and the vice presidential nominee, J.D. Vance. The New York Times calls “their shared affinity for a weak dollar” the policy that could have the “most sweeping implications for the United States and the global economy.”

“One would think that I would be thrilled with our very strong dollar,” Trump said during his White House tenure, when exporters like Boeing and Caterpillar were seen to be harmed by a strong greenback. “I am not,” he exclaimed. Mr. Vance calls a “strong dollar” the “sacred cow of the Washington consensus” and links it to “mass consumption of mostly useless imports on the one hand and our hollowed-out industrial base on the other hand.”

Yet, if a Trump-Vance ticket accedes, it’s “not clear,” the Times reports, how they “would go about weakening the dollar.” The Treasury could, say, “try to sell dollars to buy foreign currency,” or jawbone the Federal Reserve to “print more dollars.” And while a weaker dollar might make American exports more marketable abroad, it could also make imports more costly, fueling the inflation that Trump decries in his election platform.

The logic of devaluation as a means to reviving America’s manufacturing sector, though, appears hazy. After all, America had a strong dollar during two of its periods of greatest industrial growth — the late 19th century, when it was on the gold standard, and the post-World War II era, under the Bretton Woods system. In both eras paper dollars were convertible into gold at a rate fixed by law. Both periods featured high growth and low inflation.

Bretton Woods’ collapse in 1971 launched the fiat money era in which the world’s currencies, including the dollar, are untethered from the historic basis of value — gold — and gyrate in relation only to each other. So a devaluation no longer has the literal meaning it once had of reducing a currency’s value in terms of gold. It’s no wonder that in this new world, the dollar is plunging to new lows — less than a 2,459th of an ounce of gold in trading today.

In a fiat money world, devaluation is relative to other currencies. It could lead to a race to the bottom as nations seek competitive advantage by making their paper currencies ever more worthless. That might have delighted Bryan, who ran against the gold standard in his bids for the White House, most famously in 1896 when he stirred Democrats with the famous demand for free coinage of silver, vowing “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

Bryan opposed the gold standard because it kept prices in check — ostensibly hurting farmers, who wanted to be paid more for crops — and because it protected creditors, who were assured by “gold clauses” that their investments would be protected against inflation. The GOP stood for honest money that made America a safe place for foreign investment, held prices steady, and ensured that federal debt was “as good as gold,” as the party platform put it in 1896.

“We are unalterably opposed to every measure calculated to debase our currency or impair the credit of our country,” the Republicans vowed then. That was the formula that made the GOP synonymous with honest money for decades. In the heyday of the gold standard, the monetary discipline held inflation to an average of but 0.1 percent a year between 1879 and 1913. Meanwhile, today’s Fed is having trouble getting inflation down to its target of 2 percent.

Which brings us back to the Trump-Vance ticket. The 2024 GOP platform sounds a clarion call, as these columns noted, to “Defeat Inflation.” Yet the standard-bearers’ call for devaluation could end up working at cross-purposes to that goal. It’s early yet. If the executive branch persists in this effort, it could prove useful to mark how the Framers gave all the monetary powers granted to the federal government not to the president but to the Congress.