Why Is the Federal Government Charging Luigi Mangione?

The shocking murder at Midtown could be an occasion to revisit the shocking penchant for double jeopardy.

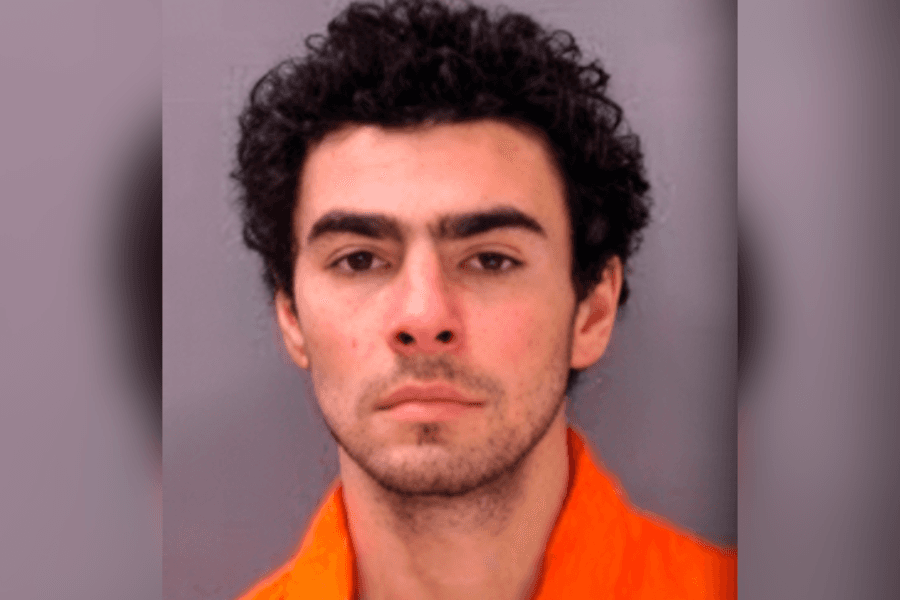

Luigi Mangione’s plea of “not guilty” in state court in New York on Monday is a moment to mark that he faces not just 11 criminal charges in the Empire State, but also four federal charges. One of the latter, murder through use of a firearm, carries a potential punishment of death. The others are two stalking offenses and one violation of gun regulations. We carry no brief whatsoever for Mr. Mangione, but wonder at the overlap.

Mr. Mangione allegedly gunned down — with bullets to the back, hushed by a silencer — the chief executive of UnitedHealthcare, Brian Thompson, on December 4. The prosecution of crime, called the “police power,” is generally a state matter. The majority of criminal code is written by state lawmakers. New York has charged Mr. Mangione with murder in the first degree and two counts of murder in the second degree, along with other crimes.

New York’s district attorney, Alvin Bragg, also accused Mr. Mangione of murdering “as an act of terrorism,” an aggravating factor that could ensure that he is sentenced to a life in prison without the possibility of parole. New York’s death penalty was declared unconstitutional in 2004, and in 2007 the last remaining death sentence was reduced to life in prison. The federal government, though, can still secure the ultimate punishment.

The Constitution ordains in the Fifth Amendment that no person shall be “subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.” The Supreme Court, though, has ruled that under the “dual sovereignty doctrine” a defendant can be charged by both the state and federal governments for the same deed. In 2019, in Gamble v. United States, the majority held that “where there are two sovereigns, there are two laws, and two ‘offences.’”

Yet Gamble has two dissents that, while not binding, are indelible. They were penned by a judicial odd couple, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The case featured a man convicted in Alabama. Uncle Sam, dissatisfied with Alabama’s sentence, charged him for the same deed. Justice Gorsuch thundered that a “free society does not allow its government to try the same individual for the same crime until it’s happy with the result.”

Ginsburg wrote that she would hold that “the Double Jeopardy Clause bars ‘successive prosecutions [for the same offense] by parts of the whole USA.’” Terance Gamble was convicted first by Alabama and received a year in prison. He then pleaded guilty to charges brought by the Department of Justice, and was sentenced to 46 months behind bars by what Ginsburg called “metaphysical subtleties” rather than constitutional bedrock.

Justice Gorsuch warns of allowing the state and federal governments to “unleash all their might in multiple prosecutions against an individual” for the same offense. He traces, with Blackstone, the ban on double jeopardy as far back as “Athens” and the “Jewish republic.” Justice Joseph Story called it “one of the great privileges secured by the common law.” Justice Gorsuch posits that an “ordinary reader” would grasp double jeopardy’s injustice.

To underscore the point, Justice Gorsuch quotes 82 Federalist, where Hamilton writes that “Different parts of the ‘WHOLE’ United States should not be positioned to prosecute a defendant a second time for the same offense.” It is no wonder that some could have doubts in respect of Mr. Bragg’s ability to pull off this prosecution. That is something New Yorkers could take with them to the polls next year, when he is on the ballot.