Who’s Your Shakespeare? New Works May Change Your Mind

Together, Lawrence Wells’s two books explore many fascinating aspects of fiction and biography, of what we choose to believe and why we often want to suspend disbelief.

‘Ghostwriter: Shakespeare, Literary Landmines, and an Eccentric Patron’s Royal Obsession’

By Lawrence Wells

University Press of Mississippi, 216 pages

‘Fair Youth’

By Lawrence Wells

Sanctuary Editions, 248 pages

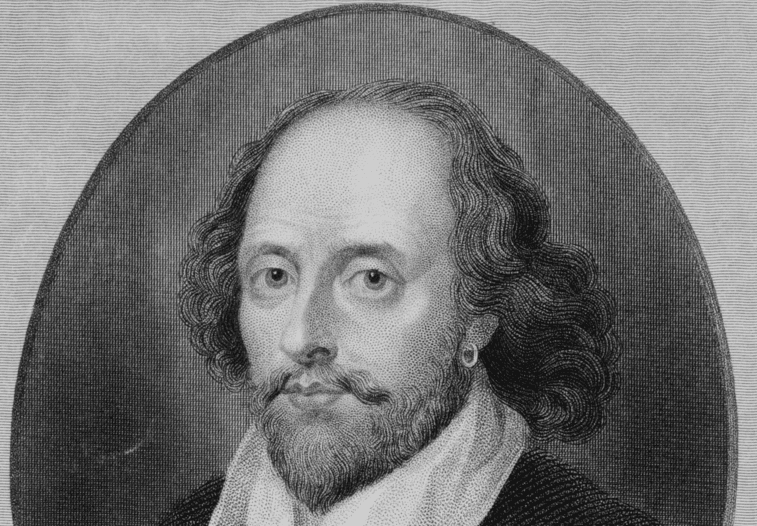

In Oxford, Mississippi, Lawrence Wells, married to William Faulkner’s niece, is invited by the University of Mississippi to ghostwrite a novel for the school’s wealthy patron, Mrs. F, an eccentric 75-year-old who promises a huge donation if Mr. Wells undertakes the project of proving that Edward de Vere, the 17th earl of Oxford, was William Shakespeare. She also happens to believe that she is the reincarnation of Queen Elizabeth I.

Mrs. F has written a play about her mania, performed in a vanity production at New York City, but has otherwise been unable to shake the world’s belief that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare. Like a maniacal monarch, she tries to control every aspect of her ghostwriter’s life, going so far as inviting her courtier (who remains fully clothed) into her bed to form an even closer collaboration.

To escape from the demanding Mrs. F, Mr. Wells embarks with his wife for England to do research for the book. He is gradually infected with his patron’s zeal and begins to actually imagine scenes that dramatize her obsessions, while he engages everyone in England in his patron’s fixation — much to the dismay of his skeptical yet loyal wife, who understands what it is like to have an obsession with the famous, having been brought up by William Faulkner after his brother Dean’s sudden death in an air crash.

This hilarious memoir/biography of a looney patron occasionally sidetracks to passages about Faulkner, another wild provincial, an unexpected genius whose example reminds Mr. Wells that you don’t have to be an earl to create great literature. Even so, the more Mr. Wells surrenders to Mrs. F’s commands, the more imaginable it is to him that Edward de Vere hid his identity as the true Shakespeare in deference to his sovereign’s wishes.

Mrs. F dies before the novel she has commissioned is completed, but not to worry because in “Fair Youth,” Mr. Wells has delivered the story she wanted told. Whatever you think of the likelihood that Shakespeare was not Shakespeare, this compelling novel confirms Hamlet’s assertion that thinking makes it so.

In “Fair Youth,” de Vere, like Mr. Wells, reports to a queen, a patron with absolute power over him, a patron who thinks it unseemly for him to declare his authorship of the plays because such work is beneath him as a nobleman. De Vere is a wonderfully realized character, in thrall to Elizabeth I even as he tries, as Mr. Wells does in “Ghostwriter,” to chart his own course, obeying his queen’s wishes and yet rebelling as well, risking punishment in the Tower of London.

Both books are also about the lure of subjection — to the rule of powerful figures, to the rule of the compelling stories. Elizabeth is as arbitrary as Mrs. F, and de Vere is, by turns, as compliant and contentious as Mr. Wells, who writes chapters Mrs. F ratifies and rejects, even as de Vere writes what he wants to Elizabeth I’s alternating delight and dismay.

In “Fair Youth,” this process of subjection and rebellion culminates in the Essex plot to remove Elizabeth I from the throne. The part de Vere plays is both to resist and abet Elizabeth’s prosecution of the rebels, when Henry, his unacknowledged son by Elizabeth, becomes part of the plot against her and may lose his life as a result.

Together, Mr. Wells’s two books explore many fascinating aspects of fiction and biography, of what we choose to believe and why we often want to suspend disbelief. If “Fair Youth” is a history of what never was, and “Ghostwriter” is a biography of what was, the synergy between the two — between fact and fiction — is haunting. Gaps in the facts will be filled, one way or another, and to be bound only by the facts, as Faulkner once said, is to live in a world deprived of the ability to imagine.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “Uses of the Past in the Novels of William Faulkner” and the editor of “British Biography: A Reader. His interview with Mr. Wells can be accessed here.