When New York Was Not Enough, or Too Much, Creative Types Turned to Sherman, Connecticut

In ‘Reflections,’ famous artists like Arshile Gorky appear in scenes that capture some of what it was like to simply be in their company, to watch and hear them, when they were off-duty, so to speak.

‘Reflections: A Gathering of Sherman Writers, Their Personal Stories and Remembrances of the Notable Artists and Writers of the 1920s to 1960s’

Gloria Allen Thorne and Virginia Zellner, Coordinators

Sherman Historical Society, 183 Pages

The small Connecticut town of Sherman “had been a farming community since its inception in 1802,” Gloria Allen Thorne and Virginia Zellner write. “Yet Sherman had a renaissance of sorts that began in the ’20s, preceding the Great Depression when a rivulet of artists and writers trickled into the area. They were seeking peace and quiet, creative inspiration, and close proximity to New York City.”

Some were seeking something else as well. One novelist, journalist, and biographer, Robert Cantwell, hid out at Sherman, hoping to escape the hounding of the FBI investigating his radical past, and the persecution of Senator Joseph McCarthy. An appearance in front of McCarthy’s congressional committee might result in blacklisting that would make the writer unemployable.

Much has been made of how McCarthy scared writers, actors, and other public figures, but much less is made of how sometimes, in small ways, the investigated stood up to intimidation — like Cantwell’s wife Betsy, who described to her Sherman friend, Ann Price, how the FBI had staked out their home, “their persistent presence” frightening the Cantwell children. Cantwell’s agitated wife “finally marched to the phone and sent a strong message directly to J. Edgar Hoover, demanding that he remove his men immediately.” Betsy’s daughter recalled: “It worked!”

Cantwell and even more so poet and critic Malcolm Cowley became fixtures in this Connecticut community, getting along well with the farmers even if, socially, they did not mingle that much. Cowley wrote for the local newspaper, and delighted in bringing William Faulkner, the self-described farmer, to Sherman; impressed with the place and people, Faulkner wrote about them.

Faulkner was very fond of Cowley’s wife, and she gets her due in this book, serving on the board of education and making sure children had hot lunches and enjoyed the “local farm excess,” the less-than-perfect produce that could not be sold but nonetheless was just as tasty and healthy.

Of course not every artist or writer fit that well into Sherman. The poet Hart Crane tried to do so, but he could not settle down — and that seems not the fault of Sherman but of a restless soul, a suicide who never was able to place himself anywhere.

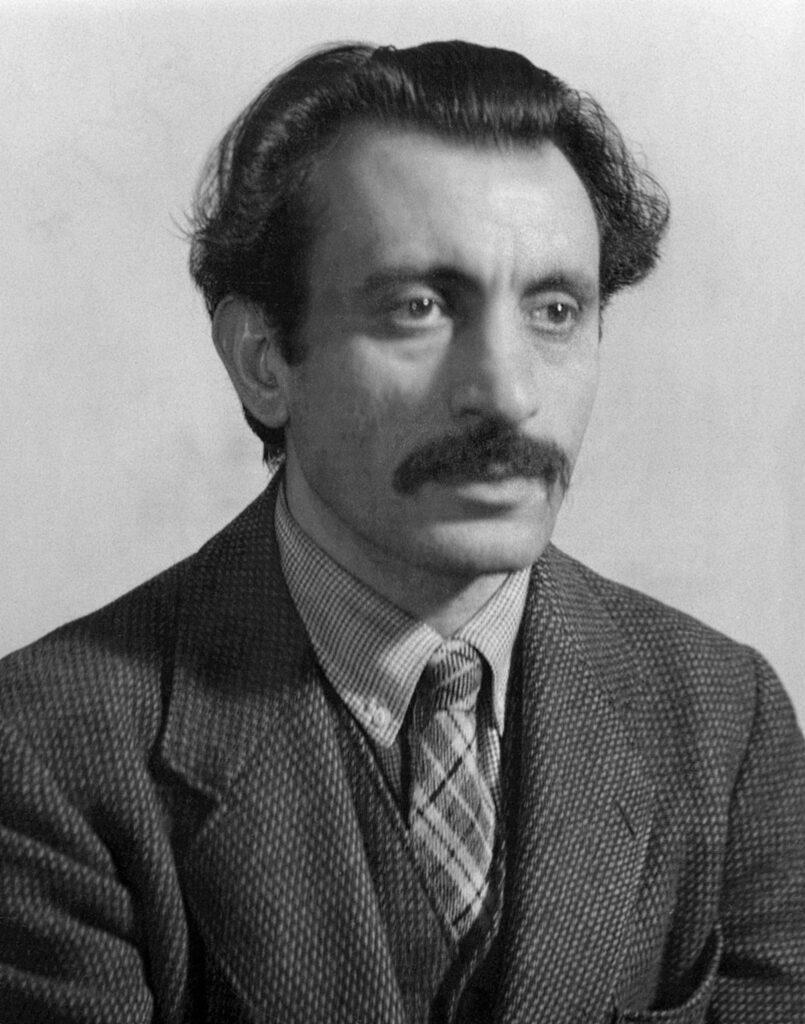

Famous artists like Arshile Gorky, who spent the last three years of his life at Sherman, appear in scenes that capture some of what it was like to simply be in their company, to watch and hear them, when they were off-duty, so to speak, and not the particular subject of any journalist’s or biographer’s study. These kinds of casual moments are valuable in the same way as I found it instructive to talk with the daughter of a Portuguese fisherman at Provincetown, Massachusetts. She caught glimpses of Norman Mailer, a local curiosity who nonetheless felt at home there.

Ann Price describes a scene in 1948, standing next to Gorky on a stair landing, looking at his paintings: “‘What do you think of this one?’ he asked. Art ignorant, I was flummoxed for a ‘worthy’ answer. Of course what the painter hoped to hear was the fresh (and honest) response of an ‘art ignorant’ young person. The painting struck me as beautiful but I didn’t know why and I surely responded with some inanity.”

Price regards this encounter as her lost opportunity — “squandered,” she says. However, the scene shows what artists wanted from Sherman: precisely that untutored response that Price calls ignorance. What a relief, one supposes, it was for Gorky to show his art to a young person in a community that unlike New York City did not consider itself presumptuous enough to criticize the artist.

Artists — famous, forgotten (except by Shermanites), or never that famous — became integral to an understanding of the community, and what that community learned about itself from contact with them.

“Reflections” has telling photographs of artists and their work, and ends with a simple and affecting sentiment, expressed by its coordinators: “We began by writing about others. To put it all in context, we wrote about ourselves. Our plan was continuity. Our discovery: in reflections, many revelations.”

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “American Biography” and “Norman Mailer: The Last Romantic.”