Was Joan Didion Even Los Angeles’s Best Writer?

A new swashbuckling double biography written with a gonzo gregariousness gives writing from California its turn in the sun.

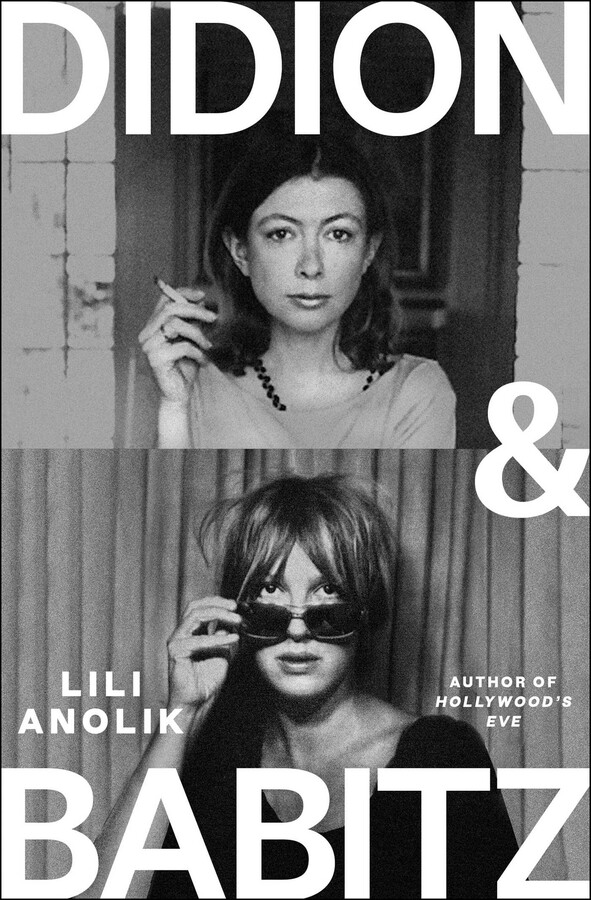

‘Didion & Babitz’

By Lili Anolik

Scribner, 352 pages

Sunshine, palm trees, and traffic — Los Angeles is the set for America’s dream of itself as flirty and fun. That Hollywood’s sensibility has been felt on the page as well as the silver screen is owed in no small measure to the yin and yang of Angelino prose — the authors Joan Didion and Eve Babitz. That is the case made by Lili Anolik in “Didion and Babitz,” a swashbuckling double biography written with a gonzo gregariousness.

To call Babitz and Didion frenemies would be like saying Interstate 405 can sometimes get busy. Didion was nine years older, steely and remote and single-minded in her focus on becoming the icon she eventually became, a sun who made other writers look like mere stars. The daughter of a Jewish musician from Brooklyn and a Cajun Catholic who converted for him, Babitz lived wildly, loved recklessly, and wrote what she knew — drugs, desire, despair.

Ms. Anolik describes these two writers in prose that borrows the style of magazine writers from another era, the time when Babitz and Didion brought California’s news as far as New York. Didion did an internship at Vogue there, wrote “Goodbye To All That,” and then decamped to California for the next 30 years. Babitz would hardly leave Los Angeles for the entirety of her life. At the end she barely even left her apartment.

Babitz was a buxom beauty, one of the disciples of Marilyn Monroe who made Los Angeles hum in the late 1950s and early 1960s. She was captured on camera — nude — playing chess with Marcel Duchamp, and dated the leader of The Doors, Jim Morrison. Ms. Anolik — who wrote a book called “Hollywood’s Eve” — calls the place Babitz’s “touchstone and guiding light.” One of Babitz’s cousins says she “had a crush on the whole scene.”

The young Babitz, Ms. Anolik writes, “was the American Dream made lush, nubile flesh.” She was also “incapable of invention” and could “write only about herself and what had happened to her.” Fortunately, a lot happened to her. Wherever the scene was, there was Babitz. She ran with “beset and bedeviled people … who knew the agony and the ecstasy and nothing in between … she found inspiration in the seamy vitality, the flamboyance and raunch.”

Babitz first imagined herself to be a visual artist, but what Ms. Anolik called her “big, unwieldy, slovenly talent” eventually found expression in memoiristic writing about the scenes she knew well. Her best book, “Slow Days, Fast Times,” says that “Los Angeles isn’t a city. It’s a gigantic, sprawling, ongoing studio. Everything is off the record.” Ms. Anolik reckons that “Slow Days” is “airy without being lightweight, blithe without being scatterbrained.”

Didion, who married young — to a writer, John Gregory Dunne — and held herself aloof from the parties Babitz threw herself into, was an early champion of the younger writer with the literary mandarins back east. Didion also edited Babitz’s first book, “Eve’s Hollywood,” until Babitz bucked under Didion’s red pen. The book’s cover, shot by Annie Leibovitz, features Babitz in a white boa and a black bikini.

Babitz in 1977 wrote a letter to the author Joseph Heller where she disclosed, “I sometimes can’t even blink I’m so enchanted. Are my enthusiasms all too shallow for words?” While Babitz was staring into enchantment, though, Didion scooped her — “The White Album” is the immortal account of the scene centered at North Hollywood that Babitz lived. Ms. Anolik reckons that Didion “captured, yet again, the geist of the zeit.”

Ms. Anolik’s heart is with Babitz, whom she interviewed more than 100 times when the writer was already, to borrow a phrase, slouching toward oblivion on account of Huntington’s disease. Didion, Ms. Anolik writes, ”always understood the stakes” and was “dead sure of her ambition.” Babitz lost her typewriter under what her sister Mirandi called “the drugs, the alcohol, the sex, the scene, all the things that she imagined fed her writing.”

Didion, though, emerges from these pages as a calculating operator, someone who “grasped the concept of branding before branding was a concept.” She also surrounded herself with people — a young Harrison Ford among them — who would provide “songs of experience, news of the times, the social ruckus, the passing circus.” Babitz was one of a cadre of what Ms. Anolik calls “handmaidens,” muses who lived the “anarchic and inventive life” she didn’t.

Ms. Anolik reckons that Didion’s memorial in 2022 at the Church of St. John the Divine was “the hottest ticket in town, proof that nobody can keep it up forever, except her.” I was one of those who scored a ticket. Justice Anthony Kennedy and Governor Brown spoke, and Pattis Smith sang. I spied the somewhat reclusive author Donna Tartt. They were all there for Didion and her aura. Babitz, a siren of sunshine, would have hated the chilliness.