‘Ulysses,’ Acclaimed as the Greatest Novel of the Last Century, Could Be Just Hitting Its Stride

James Joyce’s rollicking account of a Dublin day rewrote what a book could be.

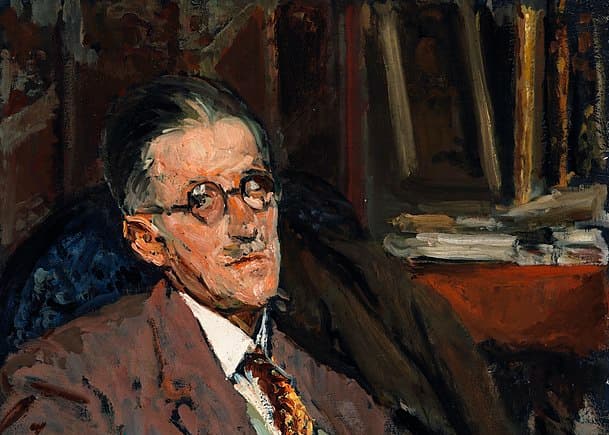

‘James Joyce’s “Ulysses”’

Directed by Adam Low

Produced by Michael Hewitt and Martin Rosenbaum

New York Jewish Film Festival

The BBC

“Ulysses” — smutty and sublime — takes as its subject one day, June 16, 1904, in the life of what was then the second city of Britain’s endless empire, Dublin. Its author, James Joyce, wrote about the perambulations of one Leopold Bloom, who leaves his home at Seven Eccles Street in the morning and returns there in the evening. In between, he encounters nothing less than the entire world. A new documentary shares the book’s madcap mastery.

“James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’” is directed by Adam Low. He has to his credits films about the painter Francis Bacon, the master drawer William Kentridge, and the Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, whose daughter Catherine narrates this stylish biography of a book. Mr. Low has assembled a murderer’s row of Anglo-Irish authors — Salman Rushdie, Colm Tóibín, Howard Jacobson, Eimear McBride, and Paul Muldoon all hold forth on Joyce’s genius.

The documentary, though, soars when it, like its subject, breaks the rules. “Ulysses” is a modernist monument that never feels like a tomb because its teeming and stream of consciousness prose jerks to high from low, puns to philosophy. The book is gridded along a classical axis — Bloom is an avatar of the famed Greek wanderer, and Joyce makes taverns the sites of Homeric grandeur. This cuckolded Irish half Jew is the hero the 20th century needed.

Take, say, the famed masticatory beginning of its fourth chapter — “Mr. Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liver slices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hencods’ roes. Most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.” Or a description of the “snotgreen sea, the scrotumtightening sea.”

Mr. Low deftly uses Joyce’s language as the score for a visually persuasive rendering of the world of “Ulysses.” Beguiling footage of Dublin over the course of the last century is spliced with clips from a movie adaptation from 1967 and various treatments of “The Odyssey,” from the canonical to the cartoon. The greatest novel of Ireland was written abroad, and the documentary delivers its sites of gestation — Trieste, Zurich, and Paris — with flair and flavor.

“James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’” persuasively argues that the book belongs not only to its author, but also to a remarkable clutch of women. First among them is Nora Joyce nee Barnacle, the model for Molly Bloom. Their love affair, conducted against a persistent undertow of privation, lent its pulse to Joyce’s prose. Then there are the magazine editors and bookshop owners — mainly lesbian women — who championed the book when it was banned for obscenity.

Because of that ban, the story of “Ulysses” is one of law as well as literature. Mr. Rushdie calls Joyce a “sexual animal,” and Mr. Low contrasts the book’s anarchic sexuality — much of it expressed by women — with Ireland’s fervent and austere Catholicism, a fortress of the faith. How remarkable, then, that Joyce’s tome is one of the greatest Jewish books since Moses got down to work. That earned it a screening at the New York Jewish Film festival.

Bloom mentions “Moses of Egypt” as well as “Moses Maimonides, author of More Nebukim (Guide of the Perplexed)” and “Moses Mendelssohn of such eminence.” He draws him as an Irish patriot who inspired Sinn Féin and hums “Hatikvah” under his breath. He tells an antisemite that “Your God was a jew. Christ was a jew like me.” He remembers ”Poor papa with his hagadah book, reading backwards with his finger to me. Pessach. Next year in Jerusalem.”

Mr. Rushdie says of Joyce that” he made everything possible,” and Molly Bloom’s soliloquy that ends “Ulysses” is a reverie of ravishment that has yet to be equaled — “I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.”