Trump’s 2020 Election Brouhaha Is ‘a Bedtime Story’ Compared to 1876 Disputed Vote, Yet No One Faced Charges

Rutherford B. Hayes’ battle against Samuel Tilden even involved allegations of coded telegrams attempting to bribe local officials to switch the counts for the Democrat.

Sixteen Michigan Republicans are under indictment for declaring President Trump victorious in their state over President Biden in 2020. Plots like these are cast as unprecedented, but America always survives electoral shenanigans, and the only thing unprecedented is the prosecution of the failed schemers by the winners.

Yesterday, Michigan’s Democratic attorney general, Dana Nessel, indicted sixteen “false electors” on felony charges for submitting a certificate stating that Mr. Trump had won the state’s 16 electoral votes, at odds with the certified count that showed Mr. Biden won by 154,000 votes.

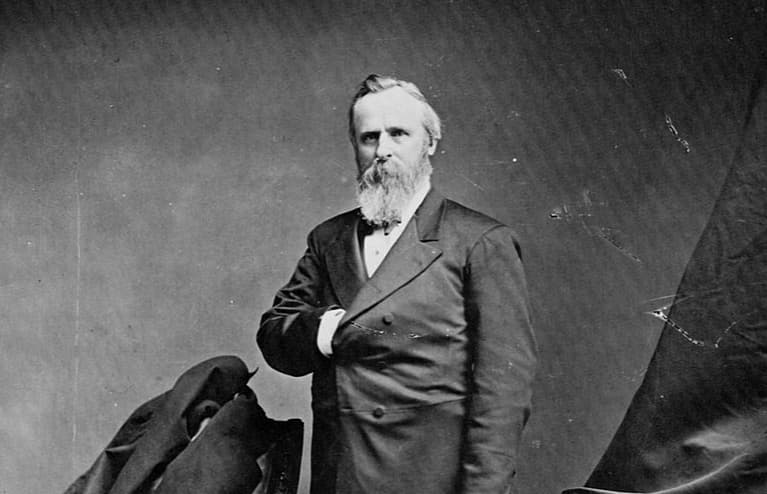

Similar cases are playing out in Arizona, Georgia, Wisconsin, New Mexico, Nevada, and Pennsylvania. It all sounds dramatic, but it’s a bedtime story compared to the 1876 election when the Republican candidate, Rutherford Hayes, faced off against the Democratic governor of New York, Samuel J. Tilden.

On that Gilded Age Election Night, the White House website says, Hayes “expected the Democrats to win” and, as returns reflected a trend against him, “went to bed believing he had lost,” until New York’s GOP chairman, Zachariah Chandler, did some quick math: Holding Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, would give Hayes 185 votes, one more than required to move into the White House.

Democratic operatives leapt into action, too. The New York Tribune published reports suggesting the Tilden campaign sought to use coded telegrams in an attempt to bribe local officials to switch the counts for Tilden. Florida’s Democratic attorney general — backed by the legislative and judicial branches — declared Tilden the winner. The state canvassing board certified Hayes.

In 2020, the winner of the elections for governor and president in Arizona were both disputed as was the case for Louisiana in 1876, which submitted competing slates of electors. President Grant, a Republican, backed Hayes, a Republican.

The Democratic candidate laying claim to the governorship, Francis Nicholls, called it for Tilden, as did a House resolution stating he was “duly elected president.” South Carolina Democrats held no positions of power but insisted that the election had been stolen by citing the lack of a voter registration law required by the state constitution.

In Congress, the Democratic representative from New York, Abram Hewitt, challenged Vermont’s certification despite a Green Mountain landslide for Hayes. The Senate overruled his objection, ignoring a package he said contained electoral votes for Tilden. Democrats backed this election denial in the House with a filibuster — a power the lower chamber retained until 1890 — holding up certification.

In Oregon, a month after the 1876 election, the Sun reported that “there was an expectation” that the state’s Democratic establishment would “give Mr. Tilden the electoral vote needed” by invalidating a Republican elector, but that plot also failed.

An Electoral Commission settled Hayes as victor rather than sending the election to the House as mandated by the Constitution when no candidate gets the required majority, now 271 electoral votes. This may have been Mr. Trump’s endgame, with Republicans having more state delegations and each getting a single ballot for president.

Holding the White House deed, of course, is no mere real estate deal to be achieved by bending local zoning laws, but presidential politics is a blood sport, and often one faction believes with sincerity that they’ve been cheated or tries every dirty trick in the book to steal an unearned victory.

The 1876 election involved clear illegalities — as did the greatest act of election denial in history, the Civil War, sparked by Democrats refusing to accept President Lincon’s victory — but none of the Tilden schemers faced changes and neither did former Confederates.

Democrats still resented Hayes, but they set their sights on the next election. Republicans had won by playing a stronger hand. Tilden’s support in the disputed states had been exaggerated by suppression of Black voters, so Republicans worked to win a clean mandate in 1880, when both Hayes and Tilden chose not to run.

Americans in 1876 looked to the future after their disputed election, healing the partisan divisions they’d created rather than keep them open and bleeding. That unity remains a noble goal, one that both the Democrats prosecuting the failed election schemers and Mr. Trump would do well to consider as they relitigate 2020 instead of moving on to 2024 with a clean slate.