The Year Christmas Movies Got Cynical: 20 Years Later, How ‘Love Actually’ and ‘Bad Santa’ Ruined the Holidays

As Christmas becomes more commercialized and consumerist, rather than being communitarian, cynicism is the counter-response one should expect.

When watching Christmas movies, two common themes one comes to expect are hope and redemption. After all, Christmas represents a day of giving. In Christmas movies, the main character is ultimately a good person. Think of “It’s A Wonderful Life,” which weighs on an ordinary man’s ability to make people happy against the boss’s greed. Then there’s “Scrooged,” a modern riff on “A Christmas Carol,” in which a rich man is sent on a journey that makes him realize his selfishness. These films show ordinary and unremarkable characters facing and surpassing existential challenges during a cherished holiday at the tail-end of the year. As they’re tied to an annual holiday, these films, if they’re any good, are guaranteed to have repeat viewings, making them a comfortable yearly watch.

Being cynical is to distrust mainstream ideas and conventions and to consider them meaningless. As Christmas becomes more commercialized and consumerist, rather than being communitarian, cynicism is the counter-response one should expect. To understand the evolution of the Christmas movie, and a crucial year for its transformation, it’s instructive to look at two Christmas-themed movies that were both released in 2003, 20 years ago.

“Love Actually” and “Bad Santa” were released a week apart. Both feature Christmas as central to the plot, but are far from wholesome. Both contain Billy Bob Thornton playing sleazy characters (in “Love Actually,” he plays a Bill Clinton-esque U.S. President). Both dealt with disappointment, both intentionally and by accident. Despite very different tones, these two films still utilize the traditional tropes of a Christmas film and end exactly in the way you would expect.

“Bad Santa” is cynical because it’s caustic by choice, centering around the antics of its titular Bad Santa in sun-baked Arizona (a setting which is deliberately as far as one could imagine from a Christmas winter wonderland). Willie is a conman who appears as a mall Santa every Christmas with his dwarf sidekick Marcus. The duo, who rob the malls where they “Santa,” have plied their trade for so many years that Marcus has become frustrated that Willie’s alcoholism and sex addiction are making their mall heists increasingly difficult. This filthy, R-rated alternative to the average Christmas film was enticing at the time, as the film’s marketers were well aware (the tagline is “He Doesn’t Care If You’re Naughty or Not”). But ”Bad Santa” is far wittier than many of its critics will acknowledge.

The film’s frequent outbursts of potty-mouthed anger are often hilarious, as “Bad Santa” finds a rhythm in Willie’s lack of motivation and Marcus’ annoyed reaction. The pair’s chemistry results in great one-liners and insults like “You need many years of therapy,” following Willie beating up a group of kids, or “more booze, more bullsh*t, more buttf*cking” followed by a rejoinder of “just the 3Bs.”

This isn’t surprising when it’s coming from Terry Zwigoff, who had previously directed the excellent “Ghost World,” featuring a pre-fame Scarlett Johansson, which has many similarities to “Bad Santa,” beginning with droll misfits and their sarcastic observations about the modern mundanities surrounding them. One important parallel between these films is the limits of sarcasm, which makes some of the characters become more detached and as alienating as the culture they criticize.

As a tale of misfits, “Bad Santa” sees Willie as a friend to the friendless Thurman Merman, a kid young and dim enough to believe that he’s hanging out with the real Santa Claus. Initially, Willie takes advantage of Thurman’s father’s house to get away from the authorities, but he evolves into a mentor for the kid. “Bad Santa” was a box office hit, and it still brings in belly laughs. It had a rather forgettable sequel released in 2016 with the returning actors, but for the grump who can’t stand Christmas, the original is a gift.

On the surface, “Love Actually” looks rather traditional and shrouds itself with optimism, beginning and ending with a scene at an airport, as a reference to the recent 9/11 attacks. But the film is ultimately cynical in how it treats its audience, in that it tries to have it every way with love. To this day, “Love Actually” still captures hearts, but 20 years later, it also remains uniquely polarizing. Christopher Orr of The Atlantic, calls it the least romantic movie ever, as most of its intersecting plotlines are driven by an ill-advised message of love – that it can be struck anywhere, not simply through the gradual build-up of characters getting to know each other. Some of the film’s match-ups end sourly, not in long-lasting romance.

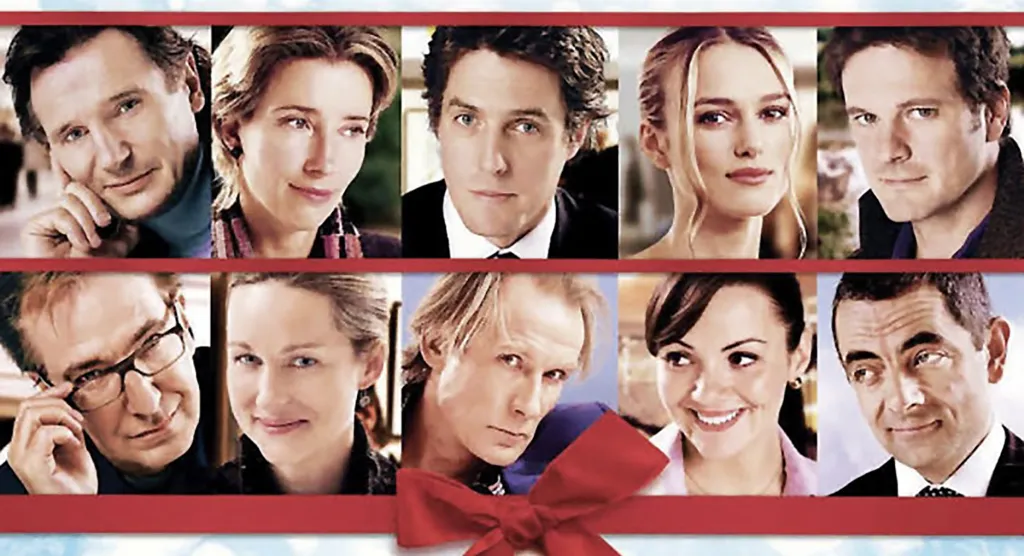

Masking its candy-coated sentiment is a mostly British ensemble cast, playing paper thin characters, defined by good looks and big hearts, with some becoming smitten with another for morally wrong reasons. And there’s no shortage of this rather limited set of stories. In one plotline, Mark (Andrew Lincoln, later to star in “The Walking Dead”) falls in love with his best friend’s newlywed wife Juliet (Keira Knightley), whom he hates for no particular reason. Another is Hugh Grant’s Prime Minister becoming more than platonic with a curvy staffer; so is Colin Firth and his migrant subordinate.

Perhaps the biggest problem facing “Love Actually” is how it maximizes the dopey fantasy version of shallow attraction over developing actual chemistry. One plotline features Sarah’s (Laura Linney) interest in a handsome co-worker, only for her opportunities to be dashed by having to take care of his mentally ill brother. Ideally, this would have been poignant, but instead it reveals her crush to be vapid and Sarah having little choice in the matter but to take care of someone far more important. But it somewhat punishes her for not taking the other choice, by not including her in the coda where all the characters reunite.

It’s even more crushing if the audience has to put themselves in the shoes of Karen (Emma Thompson), who now has to deal with her husband Harry (the late Alan Rickman), cheating on her with his promiscuous secretary.

The director of “Love Actually,” Richard Curtis, has in recent years expressed regret for some of its politically incorrect jokes. In retrospect, the film feels more like a frat bro version of a rom-com, and it becomes on the nose with another thread where two British guys go to America to score with some beautiful women. Yet the film feels more genuine when it centers on Bill Nighy’s has-been rock star whose spin on one of his hit singles hits the UK’s traditional Christmas charts, or two stunt performers becoming interested in another after having to perform a sex scene for a movie.

“Love Actually” is as soulless and smug as its title suggests. It remains significant, given Mr Curtis’ high cultural purchase in Britain, and its legacy has spawned many derivative holiday movies with similar ensembles that are even more vapid, like “Valentine’s Day” and “New Year’s Eve.” “Bad Santa” preceded further Christmas movies like “Violent Night” and “The Night Before” that dared to make the holidays more raunchy and chauvinistic. But beneath that film is an earnestness that one comes to want to watch for Christmas. “Love Actually” has a sadness that you want to avoid. And it’s the paradox of cynicism that comes to define these films.