The Shaping of the Presidency

The very first presidential biographers managed to initiate the range of approaches still in evidence today while maintaining a respectful distance from their subjects that would not be broken until 1974.

Right from the beginning, biographers have presented presidents as figures in a fable of democracy or subjects weighed down by the vexatious facts of history.

Take our first president. Parson Weems supplied the cherry tree, while John Marshall buried Washington in the minutia of public data in a five-volume unfolding of events. Washington Irving split the difference between Weems and Marshall in a lively account of the George Washington he met as a boy and as seen through the eyes of Washington’s contemporaries, many of whom were Irving’s friends.

The very first biographers managed to initiate the range of approaches to the presidency still in evidence today while maintaining a respectful distance from their subjects that would not be broken until 1974 when Fawn Brodie published “Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History,” outraging her fellow historians but nonetheless preparing the way for Annette Gordon-Reid’s revolutionary treatment of the presidency in “Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy” (1997).

In addition to bringing a more demotic style to his terms in office, Andrew Jackson inspired the form of anecdotal biography. It was pioneered by John Eaton, who had his subject straddle the divide between the obstreperous young man who defied a British officer and the mature Cincinnatus, the legendary figure of Roman virtue, sweeping away the corruption of Washington, D.C. Sound familiar?

The genre of the campaign biography was born, mixed with encomiums of presidents as natural leaders and moral exemplars, and even as ordinary men inspired to the heights of achievement by their devotion to democratic values. Martin Van Buren and James K. Polk, unable to claim Jackson’s military mantle, found biographers to distinguish them as domesticated men of high principle.

Even with a high dose of the apocryphal, campaign biographies attracted the likes of respected novelists such as Nathaniel Hawthorne and William Dean Howells. Hawthorne wrote his friend Franklin Pierce that he understood the formula and would include scenes of gallantry coupled — yes, again — with the image of the presidential candidate as a Cincinnatus.

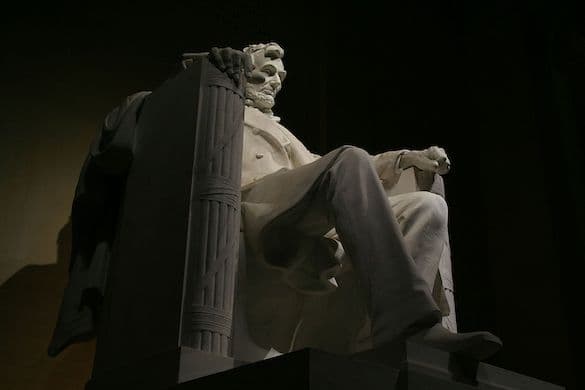

Taking on Lincoln, Howells adopted a more astringent approach, presaging a greater realism in the presentation of presidents, when he began his biography ridiculing the genre he was contributing to, noting: “It is necessary that every American should have an indisputable grandfather, in order to be represented in the Revolutionary period by actual ancestral service, or connected with it by ancestral reminiscence.”

Lincoln, of course, had no such pedigree, and Howells made the most of portraying his man as the product of the poor, educating himself into public prominence. Howells’s book signals an awareness that the electorate was beginning to tire of the campaign biography’s well-worn formulas.

Let James Parton (1822-91) stand for the new breed of presidential biographer, engineering in the “Life of Andrew Jackson” copious archival work and interviews into a riveting narrative that began with a kind of summa of previous accounts, thus injecting a new rigor and energy into the genre. It was singled out by an Atlantic Monthly reviewer, who lauded the biographer for jettisoning pedigree and valuing his subject for what he had made of himself rather than who his grandfathers were.

What Howells had begun in his Lincoln biography, Parton extended with much more lively detail, showing off his sources in a way that begins to look like the notes apparatus of present-day presidential biographies.

What was missing in Parton was an interest in the psychological, which Lytton Strachey injected into biography in the 1920s, and that Gamaliel Bradford (1863-1932) built on in what he called “psychographies” and reviews and articles about presidents as diverse as Andrew Jackson and Calvin Coolidge. Bradford helped to create what scholar Scott E. Casper calls the “culture of biography,” now familiar to readers of David McCullough and Ron Chernow.

Not until the 1960s, with the work of Theodore H. White in “The Making of the President 1960” and Norman Mailer’s journalism — most notably in his essay, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket — do the biographies of presidents change from reverence to reportorial investigations and sometimes debunkings.

Three biographers are standouts in the quest to renovate contemporary presidential biography: Nigel Hamilton, whose “JFK: Reckless Youth” was written in a rollicking style reminiscent of an 18th-century picaresque novel; Edmund Morris, whose “Dutch” was a misguided effort to re-invent himself as Ronald Reagan’s Boswell; and Alexis Coe, with his witty and irreverent “You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington.”

Other than exposés, what can we expect in a biography of President Trump? He has defied the precedents of presidential biography in so many ways that the genre will be in need of another overhauling.

Mr. Rollyson is at work on “Making the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History.”