The Morgan Centenary

If Pierpont Morgan’s era was one in which character was decisive in finance, it was also one in which money itself had character.

‘Commercial credits,’ asked the examiner, ‘are based upon the possession of money or property?’

‘No, sir,’ said Mr. Morgan; ‘the first thing is character.’

‘Before money or property?’ put in the lawyer.

‘Before money or anything else,’ repeated the witness.

— Editorial of the Sun, April 1, 1913.

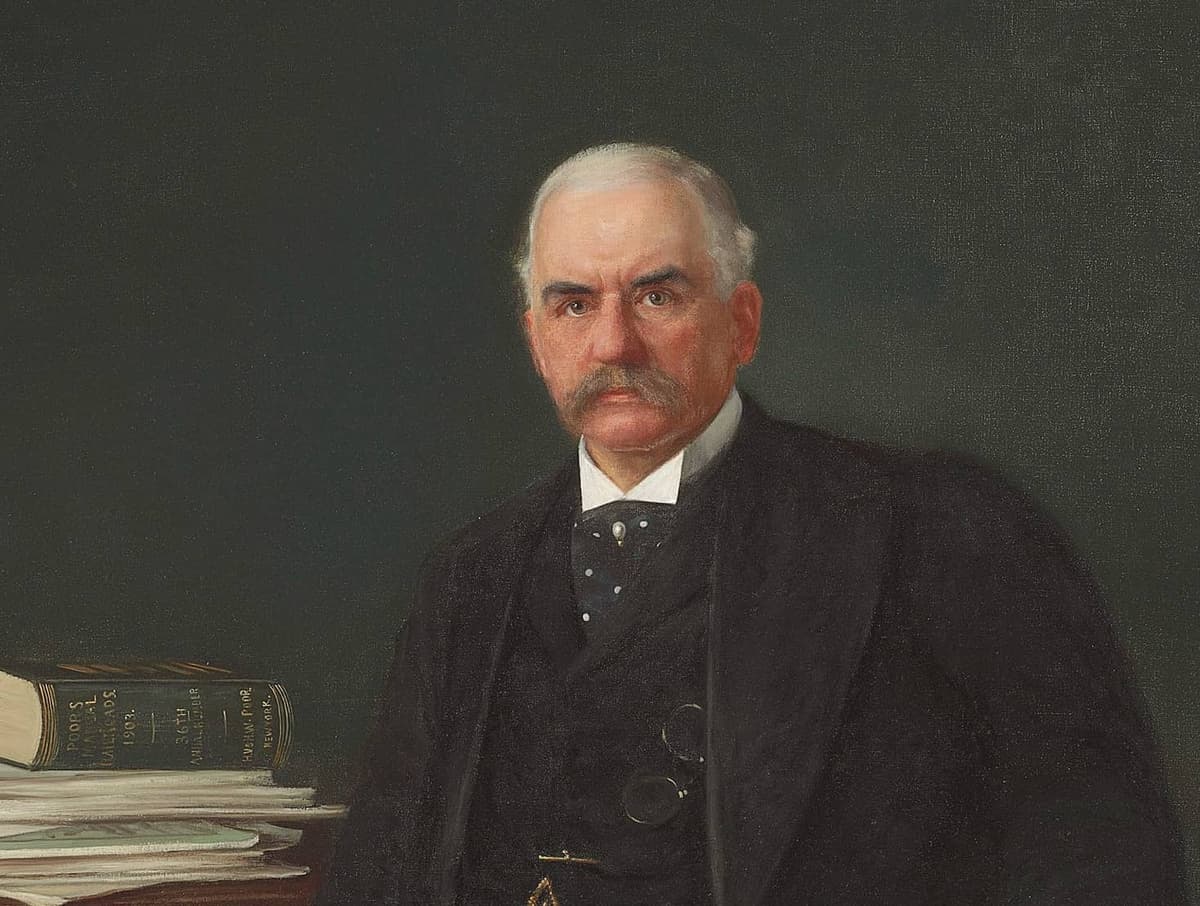

As the Morgan Library & Museum prepares to mark its centenary, our thoughts turn to the famous exchange above between its benefactor and a congressional interlocutor. Pierpont Morgan had been haled in 1912 before the Pujo committee, which was shining a spotlight on what it eyed with suspicion as the “Money Trust.” As a New York Sun editorial observed upon Morgan’s death, the financier confounded his interrogator with talk of “character.”

It was “the thing that counted,” the Sun explained, “the thing that money cannot buy.” The episode disclosed “the key to that great career of uncontested preeminence,” as the Sun put it, “among the financial and industrial leaders of the world.” If Morgan’s era was one in which character was decisive in finance, it was also one in which money itself had a character. How else to account for the use of the term “honest money” as a synonym for the gold standard?

Congressman Arsène Pujo’s panel — a subsidiary of the House Banking and Currency Committee — took exception to such notions as Morgan’s that finance and banking could manage itself on the basis of its own estimates of its practitioners’ character. In banking, economic sage James Grant has observed, the old school view was that “the first and last lines of defense of the depositor were the honor and competence” of the bankers themselves.

Surely, Progressives like Pujo insisted, the government needed to get involved — by, say, mandating public financial disclosures — to ensure “confidence” in the financial system. The idea, naive in retrospect, was that publicity would prevent “reckless lending,” Mr. Grant noted. The committee prefigured the kind of bureaucratic overregulation that would come to define the 20th century. It even set the stage for the formation of the Federal Reserve System.

Such a thing — a central bank — was seen by many as superfluous in Morgan’s lifetime. He came to be seen as almost a one-man central bank in his own right. In 1907, he averted a national financial disaster by summoning to his library in Madison Avenue his peers, the titans of finance, and brokering a pact that assuaged a banking panic. Congress at least had the decency to wait some nine months after Morgan’s death to pass the Federal Reserve Act.

The Fed was meant to insure that panics like 1907 would become a thing of the past. Progressives like Pujo designed it to rationalize banking and finance — by taking it out of the hands of bankers like Morgan. Yet at its moment of testing, the crash of 1929, the highly vaunted Federal Reserve, by its own admission, failed. Arguably, the Fed’s bungling — along with decisions like FDR’s to suspend the gold standard and devalue the dollar — made the Depression worse.

No longer are financial panics hashed out in the baronial splendor of Morgan’s library. Instead such matters tend to be resolved in the Fed’s board room at Washington — or even, when jitters strike, by Zoom — by the unelected members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee. On aesthetic grounds, few would doubt that this is a signal of decline. As to the merits of the banking system that replaced Morgan’s reliance on character, there is room for debate.

The Sun’s editorial after Morgan died noted how the financier’s “genuine love for all that is beautiful in the arts, manifested to an extent unprecedented in the history of aesthetic pursuit” had “found its constant and best reward in the gratification of others.” It is a legacy that all Americans can treasure thanks not only to the stewardship over the past century of the Morgan Library & Museum but to its namesake’s character.