Skewing George Orwell by Focusing on His Wife and Other Women

‘Wifedom’ reads like a work of fiction, no matter how Anna Funder sources her book.

‘Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life’

By Anna Funder

Knopf, 464 pages

‘Orwell: The New Life’

By D.J. Taylor

Pegasus Books, 608 pages

‘Burma Sahib: A Novel’

By Paul Theroux

Mariner Books, 400 pages

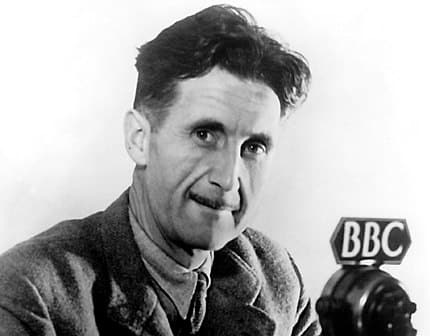

The origins of Anna Funder’s book, she reports, are to be found in a passage from George Orwell’s “private literary notebook”:

“There were two great facts about women which … you could only learn by getting married & which flatly contradicted the picture of themselves that women had managed to impose upon the world. One was their incorrigible dirtiness & untidiness. The other was their terrible devouring sexuality. … Within any marriage or regular love affair, he suspected that it was always the woman who was the sexually insistent partner. In his experience, women were quite insatiable, & never seemed fatigued by no matter how much love-making. … In any marriage of more than a year or two’s standing, intercourse was thought of as a duty, a service owed by the man to the woman. And he suspected that in every marriage the struggle was always the same—the man trying to escape from sexual intercourse, to do it only when he felt like it (or with other women), the woman demanding it more & more & more consciously despising her husband for his lack of virility.”

Ms. Funder is certain that the use of the third person is Orwell’s effort to “distance himself from feelings that were hard to own.” He had had only one wife, Eileen, at this point, and this passage must be about her. Ms. Funder “scoured” Orwell biographies and discovered that none of them quoted the passage in full and preferred to shift the responsibility away from Orwell, suggesting that the passage is a fantasy or perhaps fodder for fiction. Ms. Funder finds these interpretations “less than helpful.” In effect, she implies there has been a coverup.

Ms. Funder vents: “Orwell’s thoughts are painful to read. Women disgust him; he disgusts himself. He’s paranoid, feeling he’s been tricked by a politico-sexual conspiracy of filthy women ‘imposing’ a false ‘picture of themselves’ on the world. He sees women — as wives — in terms of what they do for him, or ‘demand’ of him. Not enough cleaning; too much sex. How was it, then, for her? My first guess: too much cleaning and not enough, or not good enough, sex. This is how I moved from the work to the life, and from the man to the wife.”

All riled up, Ms. Funder reports: “A colleague in a political office considered her [Eileen] ‘a superior person’ compared to everyone else there — a detail quoted by no biographer. … I discovered a woman who saw things and said things no one else did.” Orwell’s first marriage is given a new, fuller treatment, but the result is also a skewed portrayal of Orwell.

“Wifedom” reads like a work of fiction, no matter how Ms. Funder sources her book. She writes with the confidence of a novelist — of Paul Theroux, say, who creates an Orwell disgusted with the plummy accents of Englishwomen abroad and greatly attracted to Burmese women: “beautiful, their faces glowing, their smoothed unmarked skin like the silk slipping over it.”

D.J. Taylor, already the author of a well-received biography of Orwell, has new sources to explore. He recognizes the misogyny that Ms. Funder abhors, but he is measured in his approach to the whole subject of women, sex, and Orwell: “Harold Acton, who had a solitary conversation with Orwell in the mid-1940s, claimed to have listened to lubricious recollections of Burmese women; Leo Robertson, too, suggested to Hollis that their friend liked prowling the waterfront brothels of Rangoon; but no concrete evidence exists in either case.”

The cautious Mr. Taylor concludes: “Generally, however well or badly treated, the women stayed in touch, remained on friendly terms and cherished Orwell’s memory. The solitary exception is Mabel Fierz, who in extreme old age told a family friend that although she ‘fell for George Orwell … I wished to God I hadn’t,’ and complained about a variety of failings, including meanness.”

Ms. Funder, eschewing the humility of interpretation, is quick to draw conclusions in what Boswell called the “presumptuous task” of biography. Sooner or later a biographer is led to perch precariously on the shaky branch of fiction and fact. I’m afraid Ms. Funder has lost her balance and taken the plunge.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “Lives of the Novelists.”