Russia Retreats in the Black Sea, Opening up Odesa Ports for Grain Exports

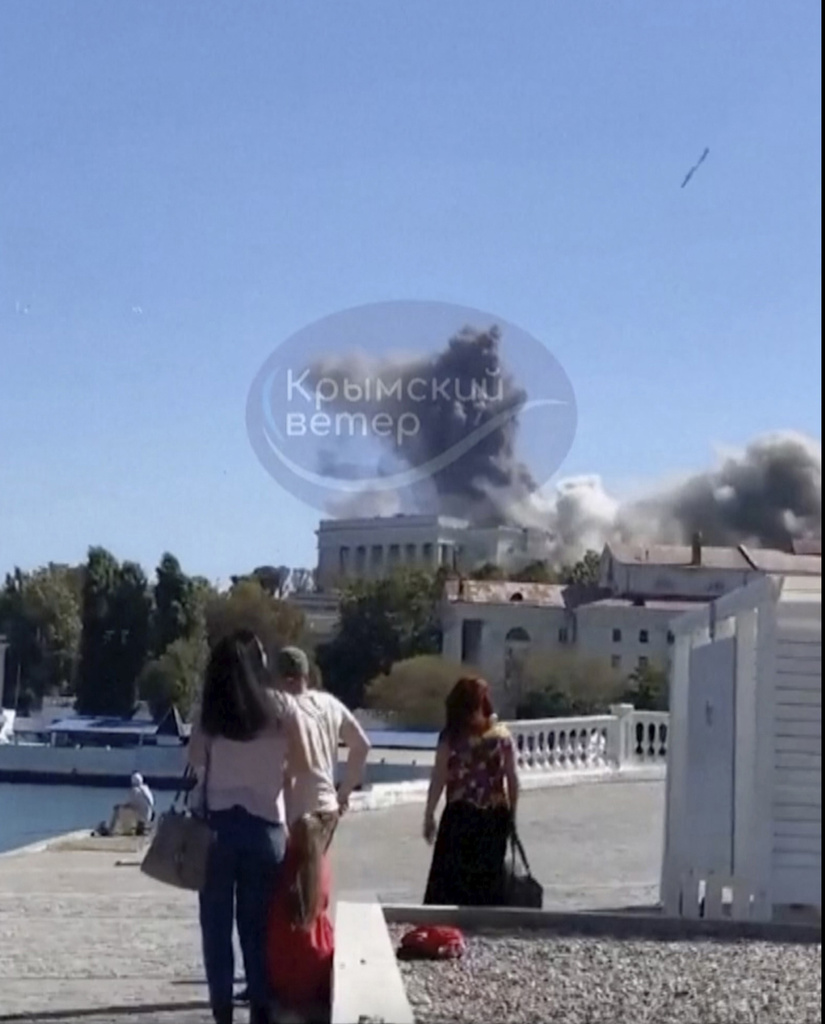

In ‘Operation Crab Trap,’ three cruise missiles found their mark at Sevastopol, headquarters of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.

By pounding Crimea with rockets and drones on a daily basis, Ukraine is winning the battle of the Black Sea. One year ago, Russian warships roamed Ukrainian waters at will, shelling Odesa and blocking exports of wheat and corn from Ukraine, the world’s fifth largest grain exporter.

In a sharp turnaround, foreign grain ships started last week to come and go from Odesa’s ports. Entering through Turkey’s Bosphorus Strait, ships hug the coasts of Turkey, Bulgaria, and Romania, all NATO members. Then, they travel a Ukrainian coastal ‘safe’ corridor protected by Ukrainian mines, drones, and rockets.

“Two outbound ships carrying grain destined for ports in Africa, Asia and the Middle East are now on their way to the Bosphorus,” the American ambassador to Ukraine, Bridget A. Brink, said in a post Saturday on X. “Despite Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative, Ukraine continues its efforts to feed the world.”

Flouting Russia’s maritime blockade, smaller ships take grain up the Danube River. Larger ships enter the Mediterranean. The first one, the Resilient Africa, is to dock at Haifa, Israel on Wednesday with 3,000 tons of Ukrainian wheat.

Fighting back, Russia fired over 30 Iranian-made Shahed drones and cruise missiles at Odesa overnight, Ukraine’s southern military command said Monday. “The sea port in Odesa suffered significant damage,” the military reported. Missiles largely destroyed the Hotel Odesa, a vacant but iconic steel and glass high-rise that loomed over the cruise ship pier, and damaged port facilities with almost 1,000 tons of grain.

For perspective, the Odesa ports exported 33 million tons of grain during the one- year export accord with Russia that expired in July. Ukraine’s Defense Ministry said the latest attack was “a pathetic attempt” to retaliate for Kyiv’s daily drone attacks on Crimea, a campaign that continued this morning.

A retired Marine Corps colonel, Andrew Bain, based in Kyiv tells The New York Sun: “There is now a lot more activity on the Northwest Black Sea as an additional way to test Russia’s critical vulnerabilities on a second front.” The no-go area for Russia’s navy in the western Black Sea is estimated to be 10,000 square miles, an area the size of Massachusetts.

Russia’s “leverage” over Ukrainian grain shipments, “will decline,” head of the State Department Office of Sanctions Coordination, James O’Brien, predicted Thursday to Reuters. Referring to the grain export agreement that Russia ditched two months ago, he said: “The factors that led Russia to believe it would benefit from withdrawing are going to change.”

The Black Sea turnaround is a David and Goliath story. Eighteen months ago, Russia ruled the waves with a Black Sea fleet that outnumbered Ukraine’s Navy by 12 vessels to one. During Russia’s 2014 occupation of Crimea, Russia seized 54 out of 67 ships of the Ukrainian Navy.

Facing an asymmetrical threat, Ukraine explored a “mosquito” naval strategy — small fast boats that would be hard to hit, but would cause outsized damage. Before the war, America delivered four surplus Coast Guard cutters and several Mark VI fast boats. After the war started, America committed to sending 18 more Mark VIs and 58 Defiants, 40-foot-long coastal patrol boats.

At the same time, Ukraine adopted its own technology to sea warfare: sea drones and Neptune missiles. The scorecard to date is impressive: 20 Russian warships and one submarine sunk or damaged. In normal times, the Black Sea fleet had 40 ships and seven submarines.

In the weeks before the war, Russia’s fleet was augmented with patrol ships sent from the Caspian Sea by canal. On March 1, 2022, one week after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Turkey invoked the 1936 Treaty of Montreux and closed the Bosphorus to the transit of warships.

On land, the fleet has been hard-hit. Over last month, Ukrainian missile and drone attacks have knocked out on Crimea:

two air defense systems, one command center, Russian radar picket lines on offshore oil platforms, the Black Sea Fleet’s sole repair dry dock, and half of the fleet’s naval aviation combat jets at Saky airbase. On Thursday, drones hit this base again.

The pièce de résistance came Friday. First Crimea was hit with a major cyberattack, then at least three cruise missiles hit the Sevastopol headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet. Although Russia has yet to disclose damages, verified cell phone videos circulate on BBC and other news outlets.

It is believed that Ukrainian pilots of Sukhoi Su-24 tactical bombers fired British-supplied Storm Shadow cruise missiles into the imposing Stalin-era building. Ukraine’s Special Forces claimed Saturday that Ukraine’s Air Force hit the headquarters at the time of a high-level meeting, resulting in “dozens of dead and wounded occupiers, including the highest management of the fleet.”

Codenamed “Operation Crab Trap” the attack may have killed Admiral Viktor Nikolayevich Sokolov, appointed commander of the Black Sea Fleet only last year.

“Hitting such an object always has a very powerful result, not only in terms of firepower, but also in terms of moral and psychological impact,” the spokeswoman for Ukraine’s southern military command, Natalia Humeniuk, said on Ukrainian TV. “Because hitting command and control points always adds more confusion to the command and control of troops.”

Under this pressure, Russia is reverting to Plan B, withdrawing much of the Black Sea fleet 200 miles east, to Novorossiysk, Russia’s main Black Sea oil export port. Twenty years ago, President Putin worried that Ukraine would not renew Russia’s lease on its naval facilities in Sevastopol. Consequently, Mr. Putin built up Novorossiysk as an alternate base for the fleet. After Russia took over Crimea in 2014, the move was canceled.

Today, all of the fleet’s subs and many of its surface ships have retreated to Novorossiysk, 175 miles up the coast of Russia’s mainland from Sochi. Last month, Ukraine’s sea drones followed them there, hitting a landing ship and a military supply tanker. Now, as in Sevastopol, most of Russia’s warships shelter in port, on constant alert for air and sea drones, and occasionally firing cruise missiles at Ukraine.

With Russia’s navy in a defensive crouch, Ukraine’s relentless Security Council secretary, Oleskiy Danilov, posted a taunt Friday that Russia’s Black Sea fleet commanders face two options: Voluntarily scuttle their boats or “be sliced up like a salami.”