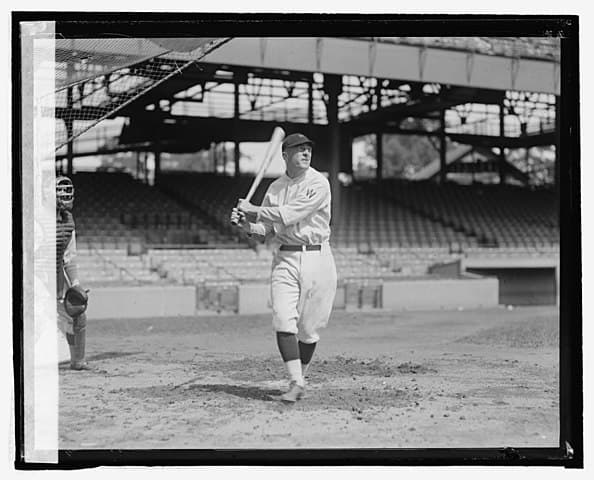

Putting Joe Judge in Hall of Fame Might Help Save Baseball

My grandfather loved the game more than money. Honoring him would reflect the best of the national pastime.

With baseball’s Opening Day being delayed and fans disgusted by greedy players and owners deadlocking over a new contract, I find myself thinking of one small step the game can take to at least earn back some small measure of goodwill.

Put my grandfather in the Hall of Fame.

A gentleman athlete, Joe Judge was versatile on the field and a quiet and decent man off it. He didn’t use chemical enhancements, making him a refreshing antithesis to the modern players who have been shunned multiple times by Hall of Fame voters, including Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Sammy Sosa.

My grandfather loved the game more than money. Honoring him would reflect the best of the national pastime. Is baseball smart enough to do it? Probably not.

Joe Judge played first base for the Washington Senators between 1915 and 1932, and then his final two seasons for the Boston Red Sox. His career stats are impressive for any era: a .298 batting average; 2,352 hits; 433 doubles; 1,034 runs batted in. He was also a whiz with the glove, five times leading the American League in fielding percentage or tied at the top. He played in the 1924 World Series, hitting .385 against the Giants.

At a 1953 Old Timers Game, the great announcer Mel Allen introduced him as “that other Washington Monument.”

After retiring, gramps coached at Georgetown University for 20 years. He gave 36 years to baseball — or, as his daughter, my Aunt Dorothy, once said, he gave “all of his heart and soul” to the game.

If baseball wants to regain some of its once gloried reputation, its Veterans Committee should put Joe Judge on the Hall of Fame ballot among other players no longer eligible for election. It would be a nod toward what is best about baseball.

My grandfather’s career began in 1915, when the Senators owner, Clark Griffith, traveled to Buffalo to scout a center fielder named Charles “Kid” Jameson.

After seeing the Bison in action, Griffith insisted that the “young first baseman ought to be thrown in the deal.” He got the 19-year-old Joe Judge for nothing while paying $7,000 for Jameson.

The Washington papers soon caught wind that a “sensational” young first baseman was going to be playing for the Senators.

On September 20, 1915, Judge arrived in Washington on a late train. Umpire Ollie Chill decided to hold up the start of the game for 10 minutes so as not to disappoint the fans. In that first game, Judge promptly delivered two hits and two RBI.

Until his death of a heart attack at 68 in 1963 — a year before I was born — Joe Judge was known and recognized by virtually everyone in Washington. Griffith Stadium held Joe Judge Day on June 28, 1930, when all proceeds went to the first baseman.

Devoting a day to a single player was a rare honor back then, but enough fans showed up to net $10,500. According to the June 29, 1930, edition of the Washington Post, Grandpa Judge was “showered with coin and gifts totaling $8,000.”

“Now Joe Judge knows how highly esteemed he is by Washington fandom. The fans made his day — Judge Day — something long to be remembered in baseball history. Orators praised him. Friends showered him with gifts and the contending clubs contributed handsomely to the purse presented to the player. It was a big time all around,” the newspaper reported.

My father, also named Joe Judge, always thought that my grandfather’s stoic personality and his career outside New York hurt him with the Hall voters. Yet there was also something else.

In 1959, my grandfather’s byline appeared with a blistering article for Sports Illustrated under the headline, “Verdict Against the Hall of Fame.” It claims that “the Hall has lost some of its meaning and much of its glory in recent years.”

If the tone seems pugnacious for such a reserved player, it’s probably because, at least according to family lore, it was actually written by Judge’s son. He was a writer for Life magazine at the time, and would go on to National Geographic.

The SI piece slammed players like Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance, who were immortalized for the poetic ring of their double-play combination — Tinkers to Evers to Chance. “Ballads … do not make base hits,” the article says, and indeed Tinker’s lifetime average was .264 and Evers’s was .270.

The article pointed to other stats of Hall of Famers, records such as catcher Ray Schalk’s lifetime .253 average and that of shortstop Rabbit Maranv, who never hit over .300. In arguing that they should have had more success, the writer says: “In my day, by the time the infield was finished spitting tobacco juice and licorice and rubbing the ball down with mud, especially on a dark afternoon, that ball would come at you looking like a lump of coal. A great hitter would lay the wood on it regardless of the side it was thrown from or of the stuff on it.”

Players in 1959, the article argued, “are not expected to throw too well or run too fast as long as they can belt the ball out of the park when their one moment of usefulness arrives.”

The words of Joe Judge — whichever one wrote the article — still ring true today. The gentleman of baseball belongs in the Hall.