Poem of the Day: ‘The Roundel’

The making of the roundel, a circular poem, becomes the making of a ring. Sounds repeat themselves with the resonant regularity of the metalsmith’s hammer.

Poems about poetry are often tedious — but sometimes not. Of course, any poetic form may prove tedious, or not, but there’s something uniquely sigh-inducing about a poem whose message is: Look at me! I’m a poem! Every poetry editor has read submission of sonnets, written under the innocent impression that no other sonnet in history has ever thought to take “The Sonnet” as its subject. Ditto the villanelle. Ditto just about every other form under the sun. The potential tedium of a pantoum about The Pantoum is almost too navel-gazingly painful to contemplate.

Nonetheless, some poets have written poems of this sort which are both instructive and clever. John Hollander (1929–2013), for instance, produced an entire book, “Rhyme’s Reason,” explaining poetic forms by casting the explanations as poems in those forms. You don’t exactly want to luxuriate in these poems, because, beyond the explanations of their forms, there’s not much there there. Still, they do come in handy for those times when you wish to write a Vietnamese lục bát, say, and need a clear, simple example to look at as you write.

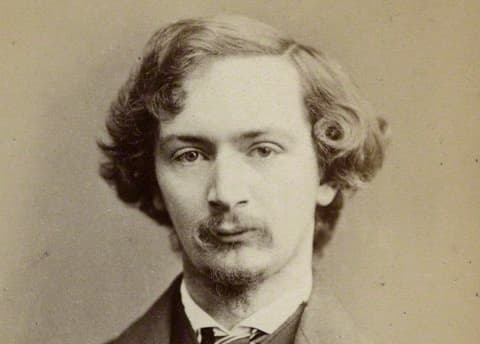

And then there are those poets, like Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909), who can make compelling music even when they’re not saying anything more than here’s how to write a roundel. Granted, the form makes enough music on its own that all the poet has to do, really, is sit down and write it — or, as in Swinburne’s case, invent it, an English derivation of the medieval French rondeau. Swinburne’s variation has eleven lines, rather than the rondeau’s traditional fifteen, broken into a quatrain, a tercet, and a quatrain, with a rhyme scheme of abab bab abab.

The poem’s opening phrase recurs as a refrain, which means that it must be a phrase that bears repeating and, ideally, accrues meaning every time it appears. Here, the choice of the verb wrought in the opening phrase supplies both some relatively easy rhymes and the imagery of the jeweler’s craft, the poem’s controlling conceit.

Additionally, the richness of internal rhyme from line to line makes the poem a delight to read aloud. All these elements, taken together, elevate Swinburne’s roundel beyond either the how-to guide or the tediously self-referential verse that pats itself on the back for existing. “The Roundel” transcends the level of the poem about poetry to become instead, in the contemporary poet Dana Gioia’s phrase, a poem about “poetry as enchantment.”

The Roundel

by Algernon Charles Swinburne

A roundel is wrought as a ring or a starbright sphere,

With craft of delight and with cunning of sound unsought,

That the heart of the hearer may smile if to pleasure his ear

A roundel is wrought.

Its jewel of music is carven of all or of aught —

Love, laughter, or mourning — remembrance of rapture or fear —

That fancy may fashion to hang in the ear of thought.

As a bird’s quick song runs round, and the hearts in us hear

Pause answer to pause, and again the same strain caught,

So moves the device whence, round as a pearl or tear,

A roundel is wrought.

___________________________________________

With “Poem of the Day,” The New York Sun offers a daily portion of verse selected by Joseph Bottum with the help of the North Carolina poet Sally Thomas, the Sun’s associate poetry editor. Tied to the day, or the season, or just individual taste, the poems will be typically drawn from the lesser-known portion of the history of English verse. In the coming months we will be reaching out to contemporary poets for examples of current, primarily formalist work, to show that poetry can still serve as a delight to the ear, an instruction to the mind, and a tonic for the soul.