Poem of the Day: ‘Snow-Bound’

The Fireside Poets were America’s 19th-century literary establishment: the poets who resided in the Parnassus of New England and set the tone for the nation’s literary taste.

We started the Poem of the Day feature in The New York Sun this past February to comment on — and set before readers again — classic works of poetry, in the conviction that poetry can still serve as a delight to the ear, an instruction to the mind, and a tonic for the soul. Along the way, the Sun has devoted weeks to the likes of Robert Frost and William Butler Yeats, presented weeks of Cowboy Poetry and poems about war, and showcased living authors of rhymed and metered verse.

And yet, somehow, over these past nine months, we seem to have neglected a little the Household Poets — the Schoolroom Poets, as they were sometimes called, or the Fireside Poets. These were America’s 19th-century literary establishment: the poets who resided in the Parnassus of New England and set the tone for the nation’s literary taste. Their poems were in every schoolbook, every anthology, every fine-press edition of America’s proudly declared native work. Everyone knew them and everyone recited them. The 20th-century turn against Victorian poetry was essentially a turn against them.

The Poem of the Day has featured a poem by Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894), while Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882) remains a presence, simply because he’s Longfellow and inescapable. But where are the rest of the old establishment? Where are the other poets read by the fireside? Where are the likes of William Cullen Bryant (1794–1878), John Greenleaf Whittier (1807–1892), or James Russell Lowell (1819–1891)?

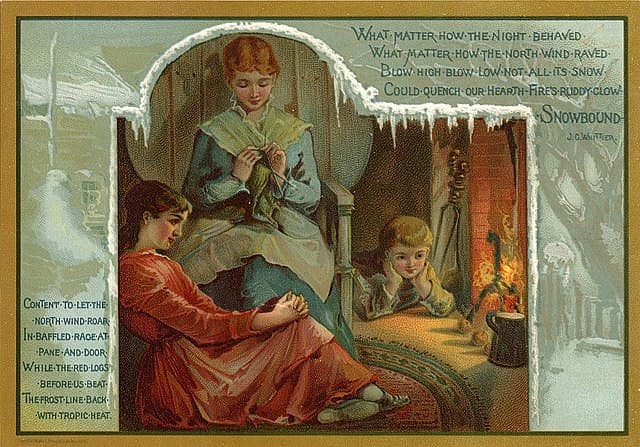

The time has come to address some of that absence, with John Greenleaf Whittier’s most famous poem, the 1866 “Snow-Bound.” Almost 800 lines long, the poem looks back in memory at the New England farmhouse in which the poet grew up, as the narrator describes being trapped by snow for a December week.

The poem was an immediate success, selling thousands of copies. Part of that came from the nostalgic tone, capturing a rural past much of America could feel fading. But part came as well from the moral argument of the poem — the claim that what keeps us from one another’s throats, cramped in small spaces, is reading aloud and telling stories: the sociality of narrative art overcoming cabin fever (as instanced in the poem itself, with its easy-reading tetrameter couplets). But the success of “Snow-Bound” also came from the sharply visual descriptions of snow and life in New England’s December landscape, as the following extract from the beginning of the poem show.

Snow-Bound [an extract]

by John Greenleaf Whittier

The sun that brief December day

Rose cheerless over hills of gray,

And, darkly circled, gave at noon

A sadder light than waning moon.

Slow tracing down the thickening sky

Its mute and ominous prophecy,

A portent seeming less than threat,

It sank from sight before it set.

A chill no coat, however stout,

Of homespun stuff could quite shut out,

A hard, dull bitterness of cold,

That checked, mid-vein, the circling race

Of life-blood in the sharpened face,

The coming of the snow-storm told.

The wind blew east; we heard the roar

Of Ocean on his wintry shore,

And felt the strong pulse throbbing there

Beat with low rhythm our inland air. . . .

Unwarmed by any sunset light

The gray day darkened into night,

A night made hoary with the swarm

And whirl-dance of the blinding storm,

As zigzag, wavering to and fro,

Crossed and recrossed the wingëd snow:

And ere the early bedtime came

The white drift piled the window-frame,

And through the glass the clothes-line posts

Looked in like tall and sheeted ghosts.

So all night long the storm roared on:

The morning broke without a sun;

In tiny spherule traced with lines

Of Nature’s geometric signs,

In starry flake, and pellicle,

All day the hoary meteor fell;

And, when the second morning shone,

We looked upon a world unknown,

On nothing we could call our own.

Around the glistening wonder bent

The blue walls of the firmament,

No cloud above, no earth below,—

A universe of sky and snow!

The old familiar sights of ours

Took marvellous shapes; strange domes and towers

Rose up where sty or corn-crib stood,

Or garden-wall, or belt of wood;

A smooth white mound the brush-pile showed,

A fenceless drift what once was road;

The bridle-post an old man sat

With loose-flung coat and high cocked hat;

The well-curb had a Chinese roof;

And even the long sweep, high aloof,

In its slant splendor, seemed to tell

Of Pisa’s leaning miracle. . . .

___________________________________________

With “Poem of the Day,” The New York Sun offers a daily portion of verse selected by Joseph Bottum with the help of the North Carolina poet Sally Thomas, the Sun’s associate poetry editor. Tied to the day, or the season, or just individual taste, the poems will be typically drawn from the lesser-known portion of the history of English verse. In the coming months we will be reaching out to contemporary poets for examples of current, primarily formalist work, to show that poetry can still serve as a delight to the ear, an instruction to the mind, and a tonic for the soul.