Poem of the Day: ‘Jordan (I)’

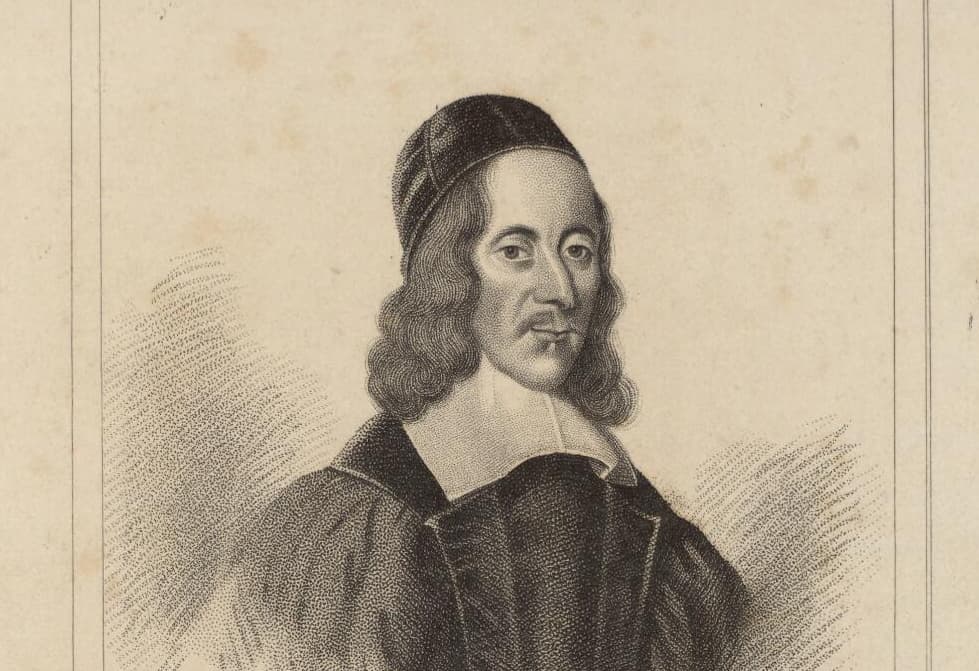

‘Who says,’ George Herbert protests at this poem’s opening, what makes a poem and what does not?

As we remarked this past Ash Wednesday, T.S. Eliot (1888–1965), in his 1946 Sewanee Review essay “What Is Minor Poetry,” takes up the “very interesting case” of George Herbert (1593–1633). What is it about Herbert that makes him so “very interesting”? Eliot’s theme in the essay is that of the “anthologized poet,” the poet whose work many people know in the typical anthology’s presentation of poems like bite-sized tapas at a Spanish bar.

Herbert, he says, might readily be dismissed as minor on the basis of the eccentric small-plate works with which people are likely to be familiar as anthology pieces: “Easter Wings,” for example, or “Love (III).” Given only that exposure to Herbert, the reader comes away with a sense of him as a mildly striking religious oddity, with none of the suavity of, for example, his contemporary Robert Herrick (whose “The Argument of His Book” appeared here only yesterday).

Please check your email.

A verification code has been sent to

Didn't get a code? Click to resend.

To continue reading, please select:

Enter your email to read for FREE

Get 1 FREE article

Join the Sun for a PENNY A DAY

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

100% ad free experience

Unlimited article and commenting access

Full annual dues ($120) billed after 60 days