Poem of the Day: ‘Her strong enchantments failing’

In a literary milieu generally thought to evince didacticism, sentimentality, and piety, A.E. Housman was not a religious believer, and he was known for a dry, mordant wit that at times could savage the pretensions of even the most accomplished classical scholars.

On a recent reading tour, I had the good fortune to visit, in the old towns north of Boston, the American poet and translator Len Krisak (b. 1948). And we spoke a little, as people do, of poems and poets we admired or disliked, or believed over- or under-appreciated. Along the way, Krisak suggested that it’s nearly impossible to over-appreciate the work of A.E. Housman. In the past year and a half, I told him, The New York Sun has offered five Housman pieces as Poem of the Day: “When I Was One-and-Twenty,” “Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries,” “Loveliest of trees, the cherry now,” “The Oracles,” and “To an Athlete Dying Young.” Surely that is, if anything, giving the Edwardian poet more than his due?

Seeing how scandalized he was, I suggested Krisak make his case. A retired English professor, he is the winner of the Richard Wilbur Prize, the Robert Frost Prize, the Robert Penn Warren Prize, and other honors. His poems have appeared in the Antioch Review, the Sewanee Review, the Hudson Review, and many other publications, while his books include his collection of verse, “Say What You Will,” and translations of such work as Virgil’s Aeneid and Rilke’s “Neue Gedichte, 1907-1908” — all rendered in English meters reflecting the metered originals. A writer of formal verse, a survivor of the anti-formalist poetry wars of the 1980s and 1990s, Len Krisak is an ideal reader of A.E. Housman.

Guest editor Len Krisak writes:

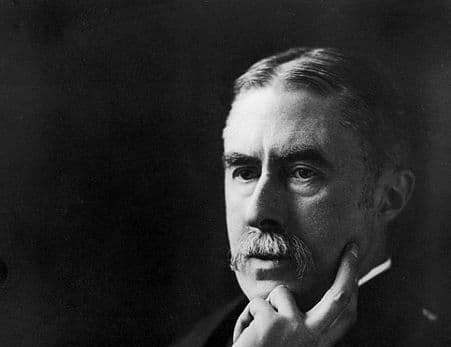

Although he was the pre-eminent classical scholar of his time, A.E. Housman (1859–1936) is best-known as the popular poet of A Shropshire Lad (1896) perhaps the best-selling volume of verse of the Victorian era. Even his later work — Last Poems (1922), More Poems (1936), and posthumously published verses — was almost as popular, and when he died in 1936, he lay buried in honors.

In a literary milieu generally thought to evince didacticism, sentimentality, and piety, Housman was not a religious believer, and he was known for a dry, mordant wit that at times could savage the pretensions of even the most accomplished classical scholars. But despite having no wish to assume the mantle of religious sage, Housman created a Shropshire that was suffused with plangent melancholy and wistful tenderness but doesn’t shy away from matters of good and evil. In “Her strong enchantments failing,” the poem labeled “III” in Last Poems, with its powerful third stanza — an accomplishment sometimes known for its shuddering frisson — Housman makes predominantly iambic trimeter terrifying.

But who is this queen of air and darkness? Readers may think of Mozart’s Queen of the Night (also a rather blood-thirsty entity), but a comparison that doesn’t take us very far. The great Housman scholar Archie Burnett provides our best clue. He points out that in Second Ephesians, a stern biblical admonition, St. Paul speaks of “the prince of the power of the air,” better known to us as the devil. And the meaning is evil.

Please check your email.

A verification code has been sent to

Didn't get a code? Click to resend.

To continue reading, please select:

Enter your email to read for FREE

Get 1 FREE article

Join the Sun for a PENNY A DAY

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

100% ad free experience

Unlimited article and commenting access

Full annual dues ($120) billed after 60 days