Poem of the Day: ‘Dover Beach’

Matthew Arnold’s poem derives its essential sadness from its sense of something lost — a decent wardrobe that once clothed the world — with only companionship remaining to dress the true nakedness of things.

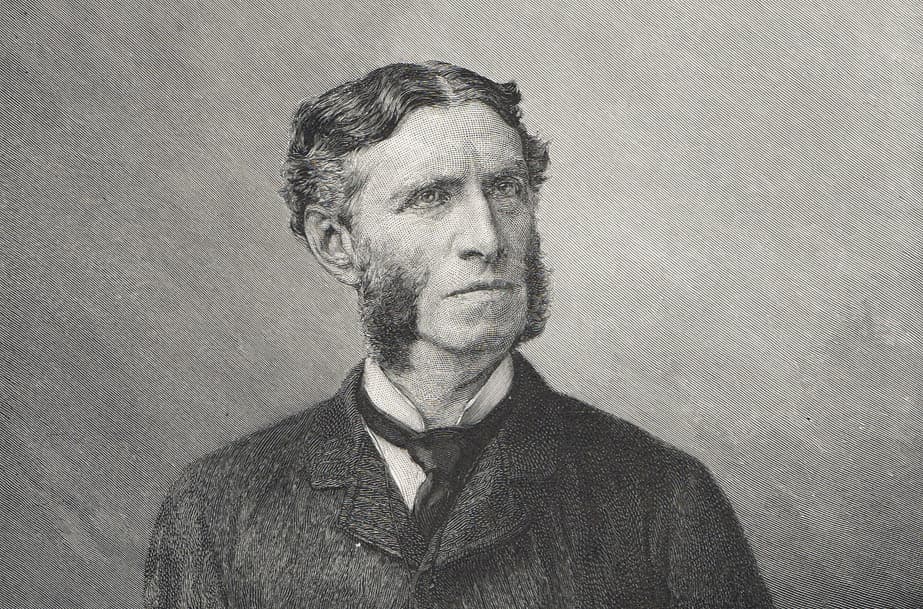

Matthew Arnold (1822–1888) saw the abyss as clearly as anyone has. He knew that meaning was fading from reality as the modern age disenchanted and demythologized the world. “Physician of the iron age,” he called the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) for seeing this effect, and in his most famous work — today’s Poem of the Day, “Dover Beach” — Arnold gives the problem of modernity one of its greatest descriptions: “a darkling plain / Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, / Where ignorant armies clash by night.”

Readers these days have a curious problem taking Arnold’s 1867 poem as seriously as they take, say, Yeats’s 1919 “The Second Coming” (Poem of the Day this past June) or Constantine P. Cavafy’s 1904 “Waiting for the Barbarians” as a fundamental poem about the modern dilemma. Arnold was often thought primarily a poet in his own time, perhaps the third in the Victorian triumvirate. But where Tennyson and Browning remained fixtures, Arnold’s place as a major Victorian poet gradually slipped. Even the American literary critic Lionel Trilling’s major 1939 study of Arnold, which he called a biography of Arnold’s mind, couldn’t restore him to our sense of the first rank.

And then there is the fact that his proposed solutions to the puzzle of modernity seem to have failed us. In “Culture and Anarchy” (1869) he famously argued for the “the best that has been thought and said,” insisting that high culture be universally taught — for these are the works in which thinkers and artists create meaning in an otherwise meaningless world. And at the end of “Dover Beach,” he posed romantic love as yet another solution.

The general culture no longer much believes in the power of high art; even the phrase “high art” feels dated, an artifact of a faded elitism. And every survey of young people suggests they would chortle at the notion that romantic love is salvific, restoring meaning to the world. Still, “Dover Beach” remains powerful, deriving its essential sadness from its sense of something lost — a decent wardrobe that once clothed the world — with only companionship remaining to dress the true nakedness of things.

Though “Dover Beach” has lines of varying length and irregular rhyming, Arnold manages to hint at something like two and a half sonnets: the 14-line first stanza, the six- and eight-line stanzas that follow, and the nine-line final stanza that reads like a broken sonnet. “The sea is calm tonight,” the poem opens, as the speaker and his love look out across the English Channel toward France — but the grinding of the sea against the shore soon lets “The eternal note of sadness in.”

Just as, in ancient Greece, Sophocles heard a message from the sea, so, near a “distant northern sea,” we hear our own message: “The Sea of Faith” once wrapped creation in meaning, but in faith’s “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,” we discern “the vast edges drear / And naked shingles of the world.” And so, Arnold cries, “Ah, love, let us be true / To one another!” The world seems “So various, so beautiful, so new” when wrapped in the meaning that new romantic love creates. But it needs that love, for the indifferent naked reality has, in truth, “neither joy, nor love, nor light, / Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain.”

Dover Beach

by Matthew Arnold

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

___________________________________________

With “Poem of the Day,” The New York Sun offers a daily portion of verse selected by Joseph Bottum with the help of the North Carolina poet Sally Thomas, the Sun’s associate poetry editor. Tied to the day, or the season, or just individual taste, the poems are drawn from the deep traditions of English verse: the great work of the past and the living poets who keep those traditions alive. The goal is always to show that poetry can still serve as a delight to the ear, an instruction to the mind, and a tonic for the soul.