Poem of the Day: ‘Autumn Song’

For Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the road that began at age twenty led inexorably to the consolations of wombats, whiskey, chloral, and the culmination of the grave. From our vantage point, this poem falls like a fatal seed.

Nobody knows, at twenty, what self-fulfilling prophecies he might be setting in motion. Nobody knows what youthful seeds will flower in an entire life’s trajectory, or how exactly those seeds will come to fruition. Nobody knows to what extent we predestine ourselves to our own outcomes, or whether in fact the whole idea of the self-fulfilling prophecy is merely an illusory function of hindsight.

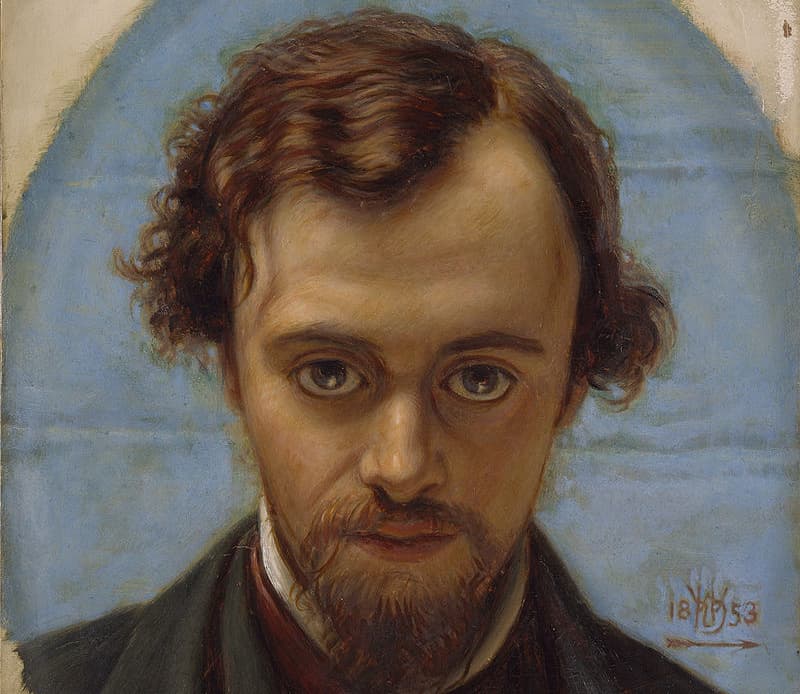

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) wrote “Autumn Song,” in 1848, the year he turned twenty. It was also the year of the founding of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which would inform his identity for the rest of his life, as well as his literary afterlife. In 1848, things were beginning to happen, but they hadn’t happened yet. As the title of the short-lived Pre-Raphaelite magazine, “The Germ,” would suggest, everything in Rossetti’s life was a seed waiting to germinate.

He had yet to meet Elizabeth Siddal, his artist’s model and wife. He had yet to bury his poems with her, after her death from an overdose of laudanum. He had yet experience second thoughts and exhume that manuscript, which included “The Heart of the Night,” for publication. He had yet to become the depressive eccentric of Number 16 Cheyne Walk, in Chelsea, keeping wombats as pets. He had yet to develop an addiction to chloral hydrate, which he chased with whiskey to mask the bitter taste. He had yet to be dead at fifty-four.

Rossetti was young when he wrote today’s poem: an old man’s poem, full of the weariness of life. Thirty years later, the young W.B. Yeats (1865–1939), who had come to London to fall under the enduring Pre-Raphaelite spell, would also write poems which assumed a self-consciously aged voice. But where Yeats’s early poems express regret for a life their author had not yet lived, the speaker in Rossetti’s “Autumn Song” longs only for release from the as-yet-unfelt pain of that as-yet-unlived life. It luxuriates in its own “languid grief” as in a bath scented with decay.

Composed of three five-line tetrameter stanzas, with an aabba rhyme scheme and a shift to trimeter in the third line of each stanza, Rossetti’s poem clearly isn’t a sonnet. Still, it offers a strange response to Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 73: “That time of year thou mayst in me behold / . . . Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.” Shakespeare’s sonnet argues that human decline, figured by the year’s waning, makes life more precious, not less. For Rossetti’s speaker, however, life is not beautiful, but futile. Only Death “seems a comely thing.”

For Rossetti himself, the road that began at age twenty did lead inexorably to the consolations of wombats, whiskey, chloral, and the culmination of the grave. He could not have foreseen any of it. His twenty-year-old self could not have planned it in all its sad, bizarre detail. But from our vantage point, at any rate, looking back, this poem falls like a fatal seed.

Autumn Song

by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Know’st thou not at the fall of the leaf

How the heart feels a languid grief

Laid on it for a covering,

And how sleep seems a goodly thing

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf?

And how the swift beat of the brain

Falters because it is in vain,

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf

Knowest thou not? and how the chief

Of joys seems — not to suffer pain?

Know’st thou not at the fall of the leaf

How the soul feels like a dried sheaf

Bound up at length for harvesting,

And how death seems a comely thing

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf?

___________________________________________

With “Poem of the Day,” The New York Sun offers a daily portion of verse selected by Joseph Bottum with the help of the North Carolina poet Sally Thomas, the Sun’s associate poetry editor. Tied to the day, or the season, or just individual taste, the poems will be typically drawn from the lesser-known portion of the history of English verse. In the coming months we will be reaching out to contemporary poets for examples of current, primarily formalist work, to show that poetry can still serve as a delight to the ear, an instruction to the mind, and a tonic for the soul.