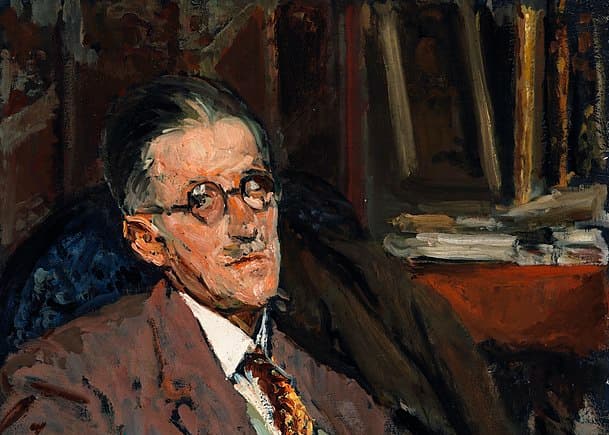

Poem of the Day: ‘A Flower Given to My Daughter’

James Joyce may be a craggy and dangerous mountain, but he is a mountain of literature nonetheless, and the literary sensibility that cannot bother reading him is neither literary nor sensitive.

If we’re going to celebrate literary birthdays in February, it’s hard to dodge the birthday of James Joyce (1882–1941) on February 2, if only because Joyce is, well, Joyce. Over the past few decades, a curious anti-Joyce sentiment seems to have taken hold among conservatives with pretensions to literary discernment.

Please check your email.

A verification code has been sent to

Didn't get a code? Click to resend.

To continue reading, please select:

Enter your email to read for FREE

Get 1 FREE article

Join the Sun for a PENNY A DAY

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

100% ad free experience

Unlimited article and commenting access

Full annual dues ($120) billed after 60 days